THE Q&A

Laurent Bouzereau wrote, produced and directed the documentary The Making of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which originally appeared on LaserDisc and has been ported over to some of the film’s subsequent home video releases.

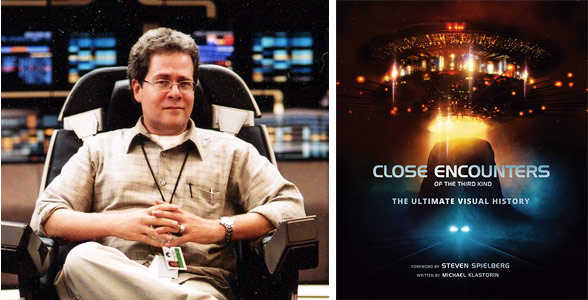

Michael Klastorin is the author of Close Encounters of the Third Kind: The Ultimate Visual History (Harper Design, 2017).

Mike Matessino produced, mixed, mastered and wrote the liner notes for the Close Encounters of the Third Kind: 40th Anniversary Remastered Edition CD release, due this fall from La-La Land Records.

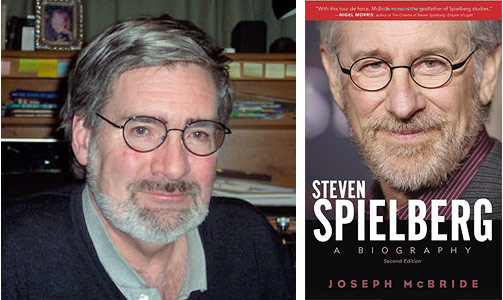

Joseph McBride is the author of Steven Spielberg: A Biography (Simon & Schuster, 1997).

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Close Encounters of the Third Kind should be remembered on its 40th anniversary?

Laurent Bouzereau: Close Encounters of the Third Kind is an extraordinary film. It’s so much more than science-fiction. After the success of Jaws, it solidified Steven Spielberg as a visionary director.

Michael Klastorin: Close Encounters should be remembered in several ways, first and foremost as a classic work of motion picture history, in terms of its story, performance and of course, in its direction.

Mike Matessino: Close Encounters is undeniably one of the most important science fiction movies ever produced, and in general one of the greatest movies ever made, period. It’s pretty amazing that it gives us a window into the world of the 1970s yet it still feels very timeless and relevant. Celebrating its 40th anniversary is a celebration of the enduring power of cinema.

Joseph McBride: A visionary film, perhaps Steven Spielberg’s greatest. It and Schindler’s List are both tremendous achievements. But some other directors (such as Roman Polanski or Martin Scorsese, whom Spielberg offered Schindler’s List when he was having anxiety about tackling it) would have made a fine film from the Thomas Keneally novel — even though maybe not as good as Spielberg’s — but no other director could have made Close Encounters at all. It is the purest expression of his personal vision and sensibility. E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial and Catch Me If You Can may be his most directly autobiographical films, but Close Encounters is his dream of a better world and his portrait of a constricted, mundane world from which his central character has to escape. Spielberg is often mistakenly viewed as celebrating suburbia, which is absurd; anyone who looks at Close Encounters with an open mind will see how horrifying and stultifying that milieu is for him. And the music-and-light show of Close Encounters is genuinely enchanting and poetic, a lyrical achievement only Spielberg could have conceived and artistically executed.

In a March 1978 letter to François Truffaut, who plays Lacombe and whose spirit suffuses the film, Jean Renoir wrote, “We have finally seen Close Encounters. It is a very good film, and I regret it was not made in France. This type of popular science would be most appropriate for the compatriots of Jules Verne and Méliès…. You are excellent in it, because you’re not quite real. There is more than a grain of eccentricity in this adventure. The author is a poet. In the South of France one would say he is a bit fada. He brings to mind the exact meaning of this word in Provence: the village fada is the one possessed by the fairies.”

Close Encounters is also Spielberg’s most spiritual movie. Carl Jung wrote in his 1959 book on flying saucers, “We have indeed strayed far from the metaphysical certainties of the Middle Ages, but not so far that our historical and psychological background is empty of all metaphysical hope…. It is characteristic of our time that, in contrast to its previous expressions, the archetype should now take the form of an object, a technological construction, in order to avoid the odiousness of a mythological personification. Anything that looks technological goes down without difficulty with modern man. The possibility of space travel makes the unpopular idea of a metaphysical intervention much more acceptable.” Jung also suggested that a belief in UFOs has “its cause in a situation of collective distress or danger, or in a vital psychic need.” The situation of collective distress that helped prompt Spielberg to make Close Encounters was Watergate, and the vital psychic need was his career-long exploration of broken families and the need to reconstitute another kind of family. Another psychiatrist who has studied the UFO phenomenon, Kenneth Ring, noted that when a child from a dysfunctional family learns “to dissociate in response to the trauma,” he is “much more likely to become sensitive to alternate realities.” That helps explains why Close Encounters unites the themes of a dysfunctional family and an alternate reality. And a friend of Steven’s parents in Cincinnati, Millie Tieger, told me, “When I saw Close Encounters, I thought, there’s Leah with the music and Arnold with computers. That’s Steve, the little boy. Steve wrote a movie about Mommy and Daddy.”

Coate: What did you think of Close Encounters, and can you recall your reaction to the first time you saw it?

Bouzereau: I saw it when it came out in Paris, on the Champs Elysées. This was before you knew everything about films before you saw them. I knew it dealt with UFOs, that it was the director from Jaws, and that France’s top director, François Truffaut, was in it. Other than that, it was a complete discovery. I remember going from being scared to completely mesmerized. It was a genuine journey that still holds up today.

Klastorin: As the film critic for my college newspaper in Brooklyn, I was invited to the very first media screening at the magnificent (and sadly, defunct) Ziegfeld Theater in New York. I sat totally engrossed from the first frame of the film, and struggled to hide the tears streaming down my face as Lacombe and the alien shared their personal moment before the Mothership departed.

Matessino: I saw Close Encounters in late December 1977 when it opened in Yonkers, New York. It was one of the films that opened the new Movieland theater, which was the first multiplex (four screens) in the area. In fact, we also had the Westchester County Dolby Stereo exclusive. It was a Sunday afternoon and I was with my father. I was extremely impressed with it and loved it from the start, but when I first saw it I was not able to fully appreciate all of its depth. Star Wars was still very much on my mind. I grew to appreciate it more after subsequent viewings including The Special Edition in 1980 and many cable airings. But E.T. in 1982, followed by the network broadcast of Close Encounters, really put the film into perspective and since then I have considered it one of my top favorites.

McBride: I have liked it enormously from the first time I saw it at a Hollywood preview when I was on Daily Variety. I saw it again in his 40th anniversary run at the Grand Lake in Oakland, California, this September and had a mild heart attack walking up a steep hill in extreme heat after the screening. But I still like it!

Coate: In what way is Close Encounters significant (among the sci-fi genre)?

Bouzereau: In the same year that Star Wars came out, it’s very interesting to have another spectacular science-fiction film with Close Encounters. Both re-invented the genre. I don’t think that kind of significant cinematic revolution has ever happened again, or at least, not for me.

Klastorin: Close Encounters was essentially the first film to seriously consider the momentous meeting between human and extraterrestrial. It was approached in a serious and thought-provoking manner, and the aliens were not portrayed as invaders, marauders, conquerors or destroyers, as they had previously been depicted since their first appearance on screen in 1898 in Georges Méliés’ A Trip to the Moon. With a visual effects team led by Douglas Trumbull in a pre-CGI era, those effects have lost none of their brilliance, and still enchant some 40 years after they were created. Consider that they were realized with a crew of 40, as opposed to the several hundred names that are crammed into the credits of today’s sci-fi features. It remains a staggering achievement.

Matessino: Close Encounters is a successor to 2001: A Space Odyssey, except it’s set in a very real present day world. It explores ideas like psychic implants and government cover-ups that are staples of the genre, but it did it in a way that was very relatable and believable. Like the best science fiction it’s a story set on an epic canvas but it’s a very personal and intimate tale about an individual and his family. I also think that it’s noteworthy in that it has no love story and no bad guy. The enemy in the movie is fear, specifically the fear or believing in something when no one around understands.

McBride: I thought it helped change the genre for the better by portraying the aliens as benevolent. A few movies had done that before, notably The Day the Earth Stood Still. Close Encounters is clearly inspired partly by Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Childhood’s End. The view of aliens as a positive force coming to Earth is characteristic of Spielberg’s liberal openness to outside influences as a grandchild of Jewish immigrants.

Coate: Which cut of Close Encounters do you like best?

Bouzereau: Nothing can replace that initial first time. So, I’d have to go with the very first version. But having been personally involved with documenting the film since 1998 through the different anniversary editions, I have enjoyed seeing how it has had several lives, and how they each speak for Steven’s vision and sensibility as an artist.

Klastorin: One always has an affinity for their first experience with a film like Close Encounters, but Mr. Spielberg himself always felt that due to budgetary and time restraints, he released the film he had to, but still wished he had been given a little more time and money to fine tune the effort. He got a rare chance to make some of those changes with the Special Edition, but he also acknowledges he never should have followed Roy Neary into that spaceship (albeit that was a demand from Columbia Pictures in exchange for the opportunity). The inside of the Mothership, he’s stated, is the exclusive property of the imagination of the audience. His third version, the director’s cut for the 20th anniversary, is his definitive version of Close Encounters. I can’t argue with that.

Matessino: Of the three that are in official release I would have to pick the original 1977 version, and one of the reasons is that I really like the scene construction starting with Roy getting fired. I think that the moment where he sees the pillow shaped liked the mountain is essential… not just because he mentions it later but because you can hear his wife Ronnie saying, “I’m not getting a job, you know.” If you think about the fact that this is the first thing a wife says when her husband gets fired, you realize that this marriage is already headed for failure and that the UFOs only helped accelerate something that was already inevitable. After that we have Roy’s return to Crescendo Summit, followed by the India, arena and Goldstone scenes. That works so much better, in my opinion, than moving the Crescendo Summit scene later. I also think you need to see Roy at the power planet early in the movie because it illustrates the randomness of what happens to him. He is in the right place at the right time and said just the right thing, which results in him — as opposed to someone else — becoming the person who has the encounter. That being said, I do like the scenes that appeared in the Special Edition, specifically the original introduction to the Neary family, the newly filmed Gobi Desert sequence and the reinstated scene with Roy in the shower. I agree with most that the interior of the mothership was not necessary; however I do like the Special Edition end credits music using John Williams’ arrangement of When You Wish Upon a Star. I would still like there to be an extended master cut that includes everything except the 1977 version of Neary’s intro (which was an insert shot later) and the interior of the mothership.

McBride: The final director’s cut. Spielberg unfortunately botched the Special Edition by inserting its anticlimactic, unimaginative ending and by cutting some of the most intense scenes of family dysfunction and some other memorable moments. At the industry screening I attended, I could tell those family scenes with Richard Dreyfuss going “mad” made people acutely uncomfortable. Seeing a father figure in an American movie going bonkers is deeply troubling to our national mythos, as was It’s a Wonderful Life on its first run. The omission of those scenes of dysfunction in the second version severely damaged the film, since they are central to Roy’s alienation and need to escape. Spielberg wisely put them back. One key scene not in the original version has the older son angrily call Roy a “crybaby,” which Spielberg recently admitted having done when his own father, during a time of family distress, broke down and cried. It’s good that the phony ending inside the space ship is now gone. It’s so much better to let the viewer use his/her imagination about what will happen to Roy.

Coate: Where does Close Encounters rank among Steven Spielberg’s body of work?

Bouzereau: It’s my second favorite after Jaws.

Klastorin: Close Encounters remains a benchmark as the first film that Spielberg both wrote and directed, and he refers to it as his most personal film. It continued the promise he had shown in his earlier television work, The Sugarland Express, and, of course, Jaws. Trying to rank his work is a gargantuan task, as he’s directed films of every genre, mixing small, personal drama with grand spectacle. Each new production holds new promise, and he seldom if ever, disappoints. I can’t wait to see what he does with Ready Player One.

Matessino: Close Encounters is the first truly personal Spielberg film and it still remains one of his greatest. It comes straight from his heart and reflects all of his passion for the medium of cinema. Without it we wouldn’t have gotten all of the wonderful films that followed. Specifically it laid the groundwork for E.T., which led to Empire of the Sun, which led to Schindler’s List. So it’s a linchpin of his career.

Coate: Where does Richard Dreyfuss’s performance of Roy Neary rank among his body of work?

Bouzereau: It’s his second best after Jaws.

Klastorin: Well before he badgered Spielberg into casting him as Roy, Dreyfuss recognized his strength in portraying the “everyman” character, and embraced it, as did audiences. His characterization of Roy Neary continued to propel him to the upper stratosphere of the acting profession and down the aisle to accept his Academy Award.

Matessino: Interesting question considering that Dreyfuss won an Academy Award for The Goodbye Girl, which came out the same year. I think he’s wonderful in Close Encounters because he truly seems like a regular guy who might live next door to you. There isn’t a false note in his performance, no moment when you feel like he is “acting.” I think it’s a performance he should look back on with absolute pride because he created a character that was relatable and real.

Coate: The role of music is of particular importance in this film since, among other reasons, the main theme appears in the film. But Spielberg has said he wasn’t sure if John Williams could deliver a good score for Close Encounters because of how great the Star Wars score turned out and that he was concerned Williams might not have had anything “left in the tank.” So how do you think the Close Encounters score turned out?

Bouzereau: I have a lot to say about this… But I’ll summarize it by mentioning that I was filming John conducting a suite from Close Encounters at a private session last year, and we were all in tears. I can only imagine what it must have been like to hear it performed for the first time. The music has not aged at all, and has contributed to the timeless nature of the film.

Matessino: Well, Close Encounters is my favorite John Williams score, and it’s interesting because I was trying to figure out how to write about it while I was in New York for the premiere of Star Wars in Concert. I spent a morning in my room working on ideas for the soundtrack notes and then stopped to go to rehearsal at Lincoln Center and it was quite jarring mentally. Star Wars is a great score, but Close Encounters is something else entirely. It serves a higher purpose and artistically reaches a lot deeper, so as with the films I don’t think the scores can really be compared one to the other. With Star Wars John Williams reached back into the history of film scoring and to a grand 19th century symphonic tradition, but Close Encounters is very contemporary and at times very experimental. It was a very bold thing to do and I think to achieve it Williams really had to push himself as a composer. Certainly what he demonstrated that year was that no one had to ever again worry that he wouldn’t be able to deliver.

Coate: Would you like to see Spielberg (or another filmmaker) make a Close Encounters sequel?

Coate: Would you like to see Spielberg (or another filmmaker) make a Close Encounters sequel?

Bouzereau: Steven told me recently that Arrival is almost a sequel to Close Encounters. So I think we’re set.

Klastorin: The short answer is, of course not. Spielberg himself flirted with the notion back in the ’80’s, but abandoned the thought soon after. How can you improve upon a classic? A sequel? There is no Close Encounter of the 4th Kind. Reboot? Why? Just for the sake of it? The original film still stands on its own, and when the newly restored 4K version played in theaters for a week a couple of months ago, it attracted enough of an audience to be held over in many of those theaters.

Matessino: In my mind (and Spielberg has said this), E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial is sort of the sequel. But as for a further story, yes, I would welcome a sequel if it were done by Steven Spielberg and handled correctly.

McBride: No! Never! The Special Edition was sort of a bungled sequel. It showed why it’s better to leave it alone (other than adding back some scenes that had been cut before the original release, as Spielberg has done). Spielberg has wisely avoided doing a sequel to E.T., unless you count the E.T. ride at Universal in which the public is whisked away to E.T.’s home planet.

Coate: What is the legacy of Close Encounters?

Bouzereau: We’re still talking about it!

Klastorin: The legacy of Close Encounters encompasses many of the facets we’ve already discussed. It’s one of the rare films that discovers new generations of audiences, as one hands it down to the next and the next. It is, with a few small exceptions, just as fresh as it was when it first illuminated the screen in 1977, and its message is still just as important.

Matessino: Close Encounters indelibly depicts first contact between humans and extra-terrestrials. It might not happen this way, but the movie shows you the way you hope it will happen. It’s also essential viewing in looking at Steven Spielberg’s body of work, which will certainly be explored long after we’re all gone. It’s also one of those rare blockbusters that isn’t about blazing guns. It’s fantasy cinema but done seriously and timelessly.

McBride: A film that helps demonstrate perhaps better than any other why Steven Spielberg is one of the greatest American filmmakers and one with a powerful and enthralling, uniquely personal vision.

Coate: Thank you — Laurent, Michael, Mike and Joseph — for participating and for sharing your thoughts about Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind on the occasion of its 40th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy Columbia Pictures, Columbia TriStar Home Video, EMI Films, RCA/Columbia Home Video, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, Voyager/The Criterion Collection.

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were regional newspaper coverage and trade reports published in Boxoffice, The Hollywood Reporter and Variety. All figures and data included in this article pertain to the United States and Canada except where stated otherwise.

SPECIAL THANKS

Don Beelik, Laurent Bouzereau, Thomas Hauerslev, John Hazelton, Bobby Henderson, Michael Klastorin, Bill Kretzel, Ronald A. Lee, Mark Lensenmayer, Stan Malone, Monty Marin, Adam Martin, Mike Matessino, Joseph McBride, Scott Neff, Cliff Stephenson, and an extra special thank-you to all of the librarians who helped with this project.

IN MEMORIAM

- Amy Douglass (“Implantee”), 1902-1980

- Eumenio Blanco (“Sunburned Old Man”), 1891-1984

- Daniel Nunez (“Federale”), 1920-1985

- Clark L. Paylow (Associate Producer/Unit Production Manager), 1918-1985

- Phil Abramson (Set Decorator), 1933-1987

- Alexander Lockwood (“Implantee”), 1902-1990

- Robert Glass (Re-recording Mixer), 1939-1993

- Norman Bartold (“Ohio Tolls”), 1928-1994

- Bill Thurman (“Air Traffic”), 1920-1995

- Merrill Connally (“Team Leader”), 1921-2001

- John Alonzo (Additional Director of Photography), 1934-2001

- Julia Phillips (Producer), 1944-2002

- Luis Contreras (“Federale”), 1950-2004

- Warren Kemmerling (“Wild Bill”), 1924-2005

- Robert “Buzz” Knudson (Re-recording Mixer), 1925-2006

- Laszlo Kovacs (Additional Director of Photography), 1933-2007

- Philip Dodds (“Jean Claude”), 1951-2007

- Shari Rhodes (Casting), 1938-2009

- Bob Westmoreland (Makeup Supervisor/“Load Dispatcher”), 1935-2009

- William A. Fraker (Director of Photography: Additional American Scenes), 1923-2010

- George DiCenzo (“Major Benchley”), 1940-2010

- Robert Broyles (“Dirty Tricks #3”), 1933-2011

- Roberts Blossom (“Farmer”), 1924-2011

- Frank Warner (Supervising Sound Effects Editor), 1926-2011

- Gene Cantamesa (Production Sound Mixer), 1931-2011

- Galen Thompson (“Special Forces”), 1940-2011

- Ralph McQuarrie (Conceptual Artwork), 1929-2012

- Carlo Rambaldi (realization of “extraterrestrial”), 1925-2012

- Matthew Yuricich (Matte Artist), 1923-2012

- Gene Rader (“Hawker”), 1926-2014

- Vilmos Zsigmond (Director of Photography), 1930-2016

- Douglas Slocombe (Director of Photography: India Sequence), 1913-2016

-Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)