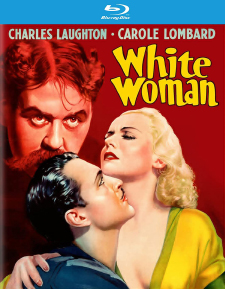

White Woman (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Stuart WalkerRelease Date(s)

1933 (February 14, 2023)Studio(s)

Paramount Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B+

- Video Grade: B+

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: B-

Review

Nineteen thirty-two and early 1933 was a busy time for Charles Laughton. Over that 18-month span he appeared in eight movies, creating memorable characters in equally memorable films, including The Old Dark House, If I Had a Million, The Sign of the Cross, Island of Lost Souls, The Private Life of Henry VIII, and the underrated Devil and the Deep. Alas, he’s embarrassingly bad in the last of these pictures, White Woman (1933), a pre-Code jungle melodrama, though a taut film, running just 68 minutes, has a terrific cast and a suspenseful, violent climax.

The film was based on a 1933 play by Norman Reilly Raine and Frank Butler called Hangman’s Whip, one that couldn’t have set Broadway on fire as it only ran 11 performances. Montagu Love played the Laughton role in that, while Helen Flint, Ian Keith, and Barton MacLane essayed roles played in the film version by Carole Lombard, Kent Taylor, and Charles Bickford.

Following the scandalous suicide of her husband and rumors of her infidelity, Judith (Lombard) is reduced to working as a café singer in Malay. British lawyer C.M. Chisholm (Claude King), doubtlessly spurred by his judgmental wife (Ethel Griffies, later famous for her role in The Birds) force Judith out of even that job, allowing “King of the Jungle” Horace H. Prin (Laughton), a self-made Cockney rubber plantation baron, to seize upon her vulnerability. He offers her his hand in marriage and, with no other option available, Judith accepts.

Deep into the hostile jungle, Prin makes his home in a decaying paddleboat, his white foreman all criminal exiles unable to escape Prin’s relentless, gleeful sadism. Disgusted by her new husband’s cruelty, she falls for overseer David von Elst (Taylor), who wants to return to civilization with Judith, but Prin refuses them a boat to get back and, anyway, he’s haunted by the experience of local natives decapitating his partner’s head, throwing it through a window, the lifeless head rolling at his feet. He’s not about to risk the dangerous trek through the thick jungle on foot. Meanwhile, new man Ballister (Bickford) arrives, and brutishly sets his sights on Judith as well.

Beautiful, talented Carole Lombard receives top billing, but Laughton’s character completely dominates the story, so much so that the film’s last few minutes all but forgets her, choosing instead to focus on his character. Laughton reportedly disliked Lombard’s working methods, but the bigger problem may have been that the actor had become typecast as sadistic eccentrics wielding abuse while dominating others, variations of which he’d already played four times in 1932. In trying to make Prin distinctive, Laughton merely is hammy. Sporting an extravagant handlebar mustache and often smoking an outrageous gourd Calabash pipe (a la Sherlock Holmes), Laughton affects a highly variable Cockney accent, wears gaudy pinstriped clothes, and would fit right in as a villain of the week on the 1960s TV Batman.

Fortunately, the supporting cast and a lively climax redeem the picture. Lombard and Taylor are fine, but Charles Bickford’s straight-talking brute makes a strong impression and his character evolves dramatically despite being confined to the film’s last 20 minutes. As doomed white foreman supervising hostile natives that Laughton’s Prin finally taunts into a full-scale rebellion, James Bell, Percy Kilbride (the future Pa Kettle making his screen debut), Charles Middleton, and a very young Marc Lawrence are all terrific. Predictably, Noble Johnson and Victor Wong, the native chief and ship’s cook in King Kong, play similar parts here.

The tense climax curiously does not show Judith and David’s last-ditch attempt to flee the plantation as it’s overrun with bloodthirsty natives, instead focusing on Prin and Ballister as they react to the growing realization that, in staying behind, they’ve likely doomed themselves to a violent, horrible end. This was probably a conceit carried over from the Broadway play, but it nonetheless serves as White Woman’s dramatic highlight, watching each man respond to an untenable situation, unwilling to exhibit fear to the other.

The direction by Stuart Walker (The Mystery of Edwin Drood, WereWolf of London), cinematography by Harry Fischbeck (The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu) and other technical credits are unremarkable, though during this time even program pictures such as these from Paramount boasted fine production values and polish.

Filmed in black-and-white for 1.37:1 projection, White Woman is presented by Kino via a new 2K restoration. Presumably the original nitrate camera negative no longer exists, but this is nonetheless a fine transfer of secondary elements, the image acceptably sharp with good contrast and strong blacks. Flaws inherent to the original production, such as hair in the camera gate, remain, but there are no signs of major damage or age-related wear. The English 2.0 mono DTS-HD Master Audio is fine given the fidelity limitations of early talkies, though the optional English subtitles do come in handy when the indulgent Laughton barely speaks above a whisper, which is often.

Extras are limited to an audio commentary track with filmmakers Allan Arkush and Daniel Kremer (the latter also a film historian). Personally, I prefer more formally structure commentary tracks allowing a denser concentration of information, but this more leisurely, conversational track does have the advantage of coming from filmmakers who point to interesting production aspects of the films other commentators often do not: the use of particular lenses, the limitations of shooting soundstage exteriors, the use of glass shots and other special effects, and so on.

White Woman is hardly Charles Laughton’s finest hour (and eight minutes), but the film itself is so short there’s no time to lose interest. Lombard and the supporting cast keep things interesting, and the climax is memorable.

- Stuart Galbraith IV