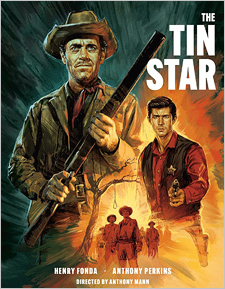

Tin Star, The (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Anthony MannRelease Date(s)

1957 (April 30, 2024)Studio(s)

Paramount Pictures (Arrow Video)- Film/Program Grade: A-

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

Director Anthony Mann helmed several exceptional film noir in the late-1940s and early- ‘50s, and later directed two of the best epic roadshows of the 1960s, El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire, but mostly he’s remembered for his outstanding psychological Westerns starring James Stewart, as well as somewhat lesser though popular films with Stewart outside that genre (The Glenn Miller Story, Strategic Air Command).

After their still-inexplicable break during pre-production on Night Passage (1957), the two never worked together again. Mann directed two more outstanding Westerns—The Tin Star (1957) and Man of the West (1958)—and a large portion of a third one (Cimarron, 1960). People often forget Mann directed The Tin Star, partly because it’s so unlike his earlier Westerns with Stewart. It’s less violent with none of the psychological tension of those films. The Mann-Stewart Westerns appeared glossy studio A-pictures, their darker, subversive elements percolating below the surface, while The Tin Star is overtly a Western with a Message.

Nevertheless, The Tin Star is exceptionally well-made with the added advantage of VistaVision, the ultra-high-resolution film format in which 35mm film ran through the camera horizontally, like a still camera. Mann and cinematographer Loyal Griggs (Shane, White Christmas, The Ten Commandments) make full use of the format’s advantages.

Bounty Hunter Morgan “Morg” Hickman (Henry Fonda) is met with suspicion and hostility when he arrives in a western town with the body of an outlaw and to claim the reward. He’s surprised to find the sheriff, Ben Owens (Anthony Perkins), cocky but hopelessly green with inexperience, Ben easily intimidated by town bully Bogardus (Neville Brand), who coveted Ben’s title. Refused a room at the only hotel, Morg befriends a half-Indian boy, Kip (Michel Ray), who invites Morg to stay at the home of his widowed mother, Nona Mayfield (Betsy Palmer).

Ben and Nona separately, gradually learn that Morg was once a sheriff until the people he protected refused to help him when his wife became ill and both she and their son died. The experience transformed Morg into a bitter bounty hunter who doesn’t believe in taking outlaws alive. Nevertheless, his time with Nona and Kip soften his hardened exterior, while Ben implores Morg to teach the neophyte sheriff the tricks of the trade. A murder committed by two half-breed brothers (Lee Van Cleef and Peter Baldwin) test Ben’s ability to control the racist Bogardus, eager to lynch them, and Ben’s determination to capture the brothers alive, against Morg’s advice.

For his part, Mann only thought the film “fair,” citing interference from the film’s producers and writer, William Perlberg and George Seaton, and screenwriter Dudley Nichols. Adept in every genre, Nichols wrote or co-wrote screwball comedies like Bringing Up Baby, solid war pictures such as Air Force, mysteries including And Then There Were None, and adventure films including Gunga Din. Particularly close to John Ford, he worked on many of that director’s best films, including The Informer, The Long Voyage Home, The Hurricane and, most notably, Stagecoach. He also wrote Frontier Marshal (1934), the basis for Ford’s My Darling Clementine a dozen years later. His other significant contribution to the Western genre was Howard Hawks’ The Big Sky.

The Tin Star appears influenced by the proliferation of TV Westerns in the late-1950s, and of “adult Westerns” like Gunsmoke particularly. At times Mann’s film more closely resembles a souped-up TV Western than, say, Paramount’s big, colorful Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, made that same year. Cinesavant’s interesting review of The Tin Star is worth quoting at length: “Dudley Nichols’ script is leavened with a few social messages, some progressive and others less so. To some degree this is a conservative Cold War movie, with the warning that eternal vigilance is the price of freedom in a dangerous world. Henry Fonda is on hand to let us know that disloyal mayors and venal businessmen aren’t worth a Sheriff risking his life over—but a real man does it anyway. It’s the Marshal Dillon Philosophy at work: wearing a badge and using violence to put bad guys in their place is the best thing for the soul. Young Ben Owens learns to command authority with confidence, and not be pushed around by a woman who wants somebody else to keep the peace. The disillusioned Morg Hickman had a family once, but lost it because uncaring citizens wouldn’t help him when he needed it. Helping Ben and Nona Mayfield inspires him to give domestic life another go with a new family. “See, we can be the World’s Policemen AND be civilized family men.”

I disagree with some of this. On Gunsmoke, Marshal Dillon’s function is to uphold law and order but, for him, violence is always a last resort. He’s a solitary figure often resented by the citizens of Dodge, and in following the rules of law he often butts heads with them as well as his own conscience, the latter never better expressed than the devastating The Gallows, perhaps the greatest TV Western episode of all-time, famous for leaving audiences speechless at the end. In The Tin Star, both Fonda and Perkins represent aspects of the Matt Dillon character. Like Fonda’s Morg, he discourages the impromptu posse, preferring to work alone, yet like Ben is determined to bring outlaws back for fair trials, even when he knows they’ll almost certainly be hanged. The conclusion of The Tin Star, in which one bad guy is gunned down, feels like a last-minute compromise to give the film the kind of violence audiences had come to expect from conventional Westerns. It reminded me of Brian De Palma’s later The Untouchables, whose violent, audience-pleasing ending seemed to contradict all that come before it.

Yet the film mirrors elements of High Noon as well, with its cowardly, resentful townsfolk, though the message here is that the glory and authority of being sheriff come with unenviable, solitary risk and responsibility: when the chips are down, you’re on your own.

Though otherwise conventional and predictable, the picture works. Partly this is due to Fonda’s fine performance; his scenes schooling Ben are captivating, the movie audience vicariously learning about the job through Perkins’s character. There are not only practical tips, like staring down a troublemaker up-close because he’s less likely to draw his gun, to more philosophical matters, like Morg explaining that reading people and observing human nature are no less important than a fast draw.

Fonda is also fine in his scenes with Betsy Palmer and child actor Michel Ray (The Space Children), scenes paralleling much of Shane but with an absent father. Born to a Brazilian diplomat and English mother, Ray appeared in several other major films, including The Brave One and David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (his last film, as one of Lawrence’s two teenage servants/lovers) then quit acting to attend Harvard, where he earned an MBA. He represented Great Britain on the ski team at the 1968 Winter Olympics, and the luge team at the 1972 and ’76 Games. He married Heineken heiress Charlene de Carvalho-Heineken, and upon her father’s death in 2002 they inherited a fortune worth almost $5 billion dollars.

Arrow Video’s Blu-ray of The Tin Star is exemplary. The video transfer provided by Paramount, clearly sourced from the original horizontal camera negative, is flawless. Mann eschews process shots and studio interiors with painted backdrops; many scenes, for instance, are set inside the sheriff’s office, which has (illogically) large windows revealing the backlot town outside: everything in the foreground and distant background is in perfect focus. On big projection screens it has an almost you-are-there effect and, as great as Gunfight on the O.K. Corral looks on Blu-ray, this better, even in black-and-white 1.85:1 widescreen. The lossless 2.0 mono track is retained, but 2.0 stereo and 5.1 surround are also offered. I selected the 5.1 option and was greatly impressed as it wisely limits the surround effects while adding considerably more weight to Elmer Bernstein’s music. (It’s a good score but aggressively omnipresent; over time he’d get more selective.) Optional English subtitles are included on this Region “A” encoded release.

Extras consist of the usual biography-heavy audio commentary by Toby Roan; Apprenticing a Master, a new video appreciation by critic Neil Sinyard; Beyond the Score, an interview with Peter Bernstein, son of the composer; a trailer and image gallery. Also included is a double-sided poster with original one-sheet art on one side, and newly commission artwork by Sam Hadley on the other; six postcard size lobby card reproductions, and a 36-page full-color booklet featuring an essay by Barry Forshaw and a reprinting of the original pressbook. It’s an excellent, imaginatively conceived package of material.

I first saw The Tin Star on DVD 25 years ago and, like director Mann, thought it just okay, but partly thanks to this new transfer and Arrow’s supplements, I’ve developed a much greater appreciation for the film.

- Stuart Galbraith IV