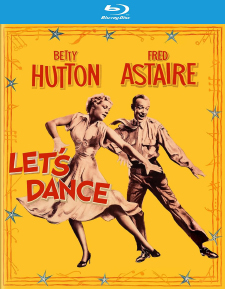

Let's Dance (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Norman Z. McLeodRelease Date(s)

1950 (February 13, 2024)Studio(s)

Paramount Pictures (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: B-

- Video Grade: B+

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B

Review

Quick! Name one of Fred Astaire’s dance partners. Likely you came up with Ginger Rogers or Cyd Charisse or Rita Hayworth. Or maybe Audrey Hepburn or Leslie Caron or Judy Garland. But I bet you never even thought of Betty Hutton. The energetic actress made one picture with Astaire, the nearly forgotten Let’s Dance. Hutton was one of Paramount’s contract stars, and the film was designed to showcase her with top billing and a more substantial story than most musicals of the period.

Kitty McNeil (Hutton, The Greatest Show on Earth) is a former USO singer and dancer whose professional partnering with Don Elwood (Astaire, Top Hat) led to a romance that Don’s aversion to marriage ended. Kitty soon married a soldier from a wealthy family. Six years later, Kitty is widowed, the mother of five-year-old Richie, and trapped in a comfortable but unhappy existence in Boston with her husband’s repressive family controlled by matriarch Serena Everett (Lucile Watson, Watch on the Rhine). Chafing under Serena’s financial thumb and her plans for Richie, she secretly carries him off one night and heads to New York to resume her musical career and bring up her son her own way.

Kitty finds that it’s tough to get back into show business, and she’s running out of money. Meanwhile, Don aspires to the world of high finance but has had no success. She and Don meet cute and he gets her a job as a cigarette girl in the nightclub where he moonlights to earn some cash. The staff loves Richie and looks after him. Ultimately Kitty and Don team up at what they both know best and become the star attraction at the nightclub, all while trying to dodge Serena and her lawyers, who are trying to serve Kitty with a lawsuit for custody of Richie.

Let’s Dance is not one of Astaire’s best musicals, primarily because the emphasis is on Hutton’s character. He’s almost a supporting player. Astaire had great success two years earlier with Easter Parade, when he came out of retirement to replace Gene Kelly. He would go on to make Royal Wedding, The Band Wagon, and Funny Face in the 1950s, all far better films, with Astaire at the forefront where he belonged. He does have an entertaining solo in Let’s Dance, playing a mean piano and dancing over, under, around, and through two pianos, which become his dance partners. This is Astaire at his finest. But his pairings on the dance floor with Hutton clearly show that the choreography by Hermes Pan was designed with Hutton’s limitations in mind.

It’s difficult to explain Betty Hutton’s popularity in the 1940s and 1950s. In every film of hers I’ve seen, she’s unvaryingly frenetic, her body constantly in motion, her eyes wide as dinner plates, her face as frantic as if an asteroid is about to crash into the Earth. There’s hardly any nuance or variety. She’s fine in broad comedy numbers but beyond her depth in dramatic moments, so the serious plot of a mother trying to retain custody of her child is a poor fit. When she should be thoughtful and introspective, she broadcasts her character’s feelings. Director Norman Z. McLeod failed to rein her in. This plot is more dramatic than in typical musicals of the time and requires a stronger female lead.

Let’s Dance boasts an excellent non-musical supporting cast, including Ruth Warrick, Barton MacLane, Sheppard Strudwick, and Roland Young, who infuse some life into the story.

The score is by Frank Loesser (Where’s Charley?, Neptune’s Daughter), who had a huge success on Broadway the same year with Guys and Dolls. He won an Academy Award for the song Baby, It’s Cold Outside and would go on to write the melodic score for the film Hans Christian Andersen. But the songs in Let’s Dance are neither particularly tuneful nor clever. Hutton kicks off the film promisingly with its best song, I Can’t Stop Talking About Him, a rapid-fire ditty well suited for her energetic persona. Astaire has a clever number much later—Jack and the Beanstalk, a jazzy version of the fairy tale with Wall Street-inspired lyrics that hapless wannabe financier Don sings to Richie while bouncing on a bed to entertain his audience of one. None of the other numbers come close to measuring up.

A slapstick comedy duet, Oh, Them Dudes, has the stars costumed and made up as two men in stereotypical cowboy garb, cavorting and rough- housing in a saloon as they twang out the uninspired lyrics and fire six-shooters. Astaire had previously had success in comedy numbers with Judy Garland (A Couple of Swells, with Garland dressed and made up as a man) and Jane Powell (How Could You believe Me When I Said I Loved You When You Know I’ve Been a Liar All My Life), but Oh, Them Dudes lacks charm and seems terribly forced as Astaire and especially Hutton strain to milk laughs out of tepid material. Hutton’s romantic number, Why Fight the Feeling, and dance duet with Astaire are lackluster. The finale number, Tunnel of Love, is mundane and forgettable.

Allan Scott and Dane Lussier’s screenplay, based on a story by Maurice Zolotow, attempts to combine comedy and drama in a talky musical that, at 122 minutes, long outstays its welcome. Astaire and Hutton are so ill-matched—she’s hectic, he’s debonair—that there’s an utter lack of chemistry between them. They show little connection to one another and seem to be dutifully reciting their lines. Their dances have nothing close to the magic that Astaire brought to his duets with Rogers. Director McLeod made many successful comedies with the Marx Brothers, W.C. Fields, and Bob Hope, but Let’s Dance never achieves their level of wit.

Let’s Dance was shot by director of photography George Barnes on 35 mm film in Technicolor with spherical lenses and presented in the aspect ratio of 1.37:1. The Blu-ray from Kino Lorber was remastered in HD by Paramount Pictures. The color palette is more subdued than in typical Technicolor musicals, with soft pastels dominating rather than vivid primary hues. In fact, several sequences appear to be either washed out or intentionally desaturated. The one exception is Betty Hutton’s make-up, with her red lipstick and rouged cheeks practically popping out of the screen.

The soundtrack is English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio. English SDH subtitles are an available option. Dialogue is clear and distinct. The musical numbers sound robust, though the mono track doesn’t allow for specific instruments to stand out. Sound effects include pistols being fired in the Oh, Them Dudes number, ambient nightclub noise, pots and pans rattling and, of course, Astaire’s footwork.

Bonus materials on the Blu-ray release from Kino Lorber include the following:

- Audio Commentary by Author/Film Historian Lee Gambin

- Daddy Long Legs Trailer (2:42)

- Has Anybody Seen My Gal Trailer (2:33)

- Flower Drum Song Trailer (2:45)

- A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum Trailer (2:23)

- Thoroughly Modern Millie Trailer (2:39)

- Change of Habit Trailer (2:49)

- Sweet Charity Trailer (1:39)

- The Paleface Trailer (1:50)

Audio Commentary – Gambin refers to Let’s Dance as a “custody battle musical.” It was an attempt by Paramount to capitalize on the success of MGM’s Easter Parade by pairing Fred Astaire with studio star Betty Hutton. By the 1950s, musicals were glossy, though some plots about struggle were incorporated. Paramount’s musicals were more grounded than those of MGM, with a lot of emphasis on story as well as on showcasing a star. Hutton is the female equivalent of Danny Kaye, a performer who can deliver a patter song such as I Can’t Stop Talking About Him. There was a sense of urgency to find love during World War II because of the unpredictable global upheaval. Women entertainers were supposed to represent any soldier’s sweetheart. Kitty longs for security, which she finds in show business, a contradictory notion. Kitty is just as displaced as men returning from the war. Writer Allan Scott was known for co-writing many of the Astaire/Rogers films and was especially adept at writing for women and dealing with class issues. Astaire’s career is chronicled from his early years teaming up with sister Adele on Broadway, his desire to work as a soloist after Adele’s retirement, his pairing with Ginger Rogers at R-K-O, and George Gershwin’s admiration for his singing voice, which had “a swagger.” A screen test for David O Selznick didn’t impress. Astaire didn’t look like the typical leading man but on screen, his dancing transformed him into something special. Dancing Lady was his first film and he impressed its star, Joan Crawford, whose praise drew attention from other studios. Astaire and Rogers did nine pictures together. Astaire wanted the songs and dances to further the plot and let emotion come through in dance. When he’s not dancing, Astaire comes across as a sophisticate with a flair for comedy. Betty Hutton’s first feature was The Fleet’s In (1942). Her early films are noted along with her growing popularity. She was also a recording artist who released popular songs on the Capitol label. The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) made her a star and became a “massive success” despite its controversial premise. She co-starred with many leading men, including Fred MacMurray, Bing Crosby, Victor Mature, and Howard Keel. She starred in Annie Get Your Gun, replacing the ill Judy Garland, the same year she made Let’s Dance, which did not do nearly as well at the box office. Hutton’s career faded fairly quickly due to mental health struggles.

Let’s Dance is an interesting picture. It shows that when Astaire is paired with a partner whose dancing ability is so far inferior to his own and he’s relegated to second fiddle, the film doesn’t sparkle. For Astaire fans, it’s worth a look, but for those seeking examples of Astaire at his finest, it’s best to check out his 1930s films with Ginger Rogers, Easter Parade with Judy Garland, and The Band Wagon with Cyd Charisse. As for his use of gimmickry in dance, there’s no film better for that than Royal Wedding.

- Dennis Seuling