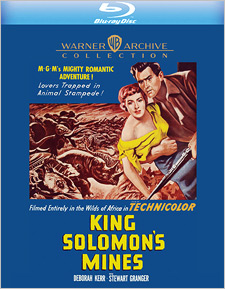

King Solomon’s Mines (1950) (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Compton Bennett/Andrew MartonRelease Date(s)

1950 (May 30, 2023)Studio(s)

MGM/Loews, Inc. (Warner Archive Collection)- Film/Program Grade: A

- Video Grade: A

- Audio Grade: A-

- Extras Grade: B-

Review

Its gorgeous 3-strip Technicolor beautifully restored in 4K by the Warner Archive, King Solomon’s Mines (1950) has always been one of MGM’s biggest and most successful adventure spectaculars but, put into context, it’s even more interesting watching it now.

Jungle movies were a staple Hollywood genre for the entire 1930s and ‘40s, not really petering out until the early-1960s. Earlier seminal films like Trader Horn, King Kong, and Tarzan and His Mate established genre conventions for big and small-scale films, nearly all of which were in black-and-white and filmed on a combination of soundstage exteriors and locations near Hollywood: Griffith Park, the Los Angeles Arboretum, Bronson Canyon, etc.

Probably the single-most overworked plot in all of classical Hollywood cinema goes like this: a jungle veteran—always Caucasian, as in Tarzan, Jungle Jim, or similar Great White Hunters—is tasked by a wealthy, often spoiled young woman to locate her missing brother/husband/father, who got lost in the jungle researching an obscure tribe or searching for a long-lost treasure. B-Westerns endlessly recycled one of four or five basic plots, but the above probably describes at least 75% of jungle movie storylines—including King Solomon’s Mines.

The difference, of course, is that MGM’s film was lavishly produced on location in Uganda, the Belgian Congo, Tanganyika, and Kenya with production values and using technical resources far beyond the means of all but Hollywood’s wealthiest studios. The $2.3 million film (expensive by 1950 standards) grossed more than $15 million worldwide, and so successful it prompted other filmed-in-Africa almost at once, including The African Queen (1951), Tarzan’s Peril (the first to be partly shot in Africa, also 1951) and MGM’s own follow-up, Mogambo (1953).

Loosely adapted from H. Rider Haggard’s 1885 novel, as well as the 1937 British film version, MGM’s film opens on a distressing note, as Allan Quatermain (here called Allan Quartermain, and played by Stewart Granger) is leading two Germans on safari (one played by John Banner of Hogan’s Heroes) as one shoots an elephant. The onscreen killing was not faked and other distressed elephants gather around the mortally wounded animal, pathetically trying to lift it, footage reportedly never captured on film before or since.

Englishwoman Elizabeth Curtis (Deborah Kerr) and her brother, John Goode (Richard Carlson) approach Quartermain to lead them deep into uncharted Africa to locate Elizabeth’s husband, who had been searching for the legendary diamond-rich mines. Quartermain refuses at first, put off especially by the notion of traveling with a woman, but when she offers 5,000 pounds in advance, mercenary Allan can no longer refuse.

The trio and their army of bearers, led by Khiva (Kimursi), face the usual jungle threats: deadly snakes and spiders, crocodiles, a rhino, a stampede of wildebeests and other mammals. Indeed, in its 103 minutes King Solomon’s Mines makes room for prime footage of practically the entirety of the animal kingdom, 10 hours of David Attenborough documentary crammed into a two-hour movie. In one particularly amusing sequence, the trio notice some exotic animal, take several steps, Quartermain points to some other colorful creature and, a few steps further on, points to something else, and something else, and so on, a veritable minefield of critters. Unlike cheap jungle pictures, however, with their constant cutaways to obvious and often grainy stock footage, everything here is original to the film, the animals often interacting directly with the three principals and/or their stunt doubles.

Eventually seven-foot-tall Watusi Umbopa (Siriaque) joins the party, and later they encounter a suspicious white man, “Smith” (sometime director Hugo Haas), living among yet another tribe. Eventually they reach Umbopa’s village, near the fabled mines, but where evil usurper Twala (Baziga) has become King, his rule threatening a civil war.

Except for the graphic killing of the elephant in the opening scene, King Solomon’s Mines is neither particularly politically incorrect nor is it particularly progressive. All of the “natives” in the film are played by indigenous non-actors, and are generally treated respectfully instead of as the subservient negative racial stereotypes often found in this type of movie. Rare for such films, Stewart Granger speaks actual Kiswahili in the film in many long dialogue scenes with local tribesmen, adding verisimilitude.

Indeed, the picture is impressively credible for what it is, though unsurprisingly Deborah Kerr’s character maintains perfectly coiffed hair and makeup (except for a few carefully-positioned smudges and mussed hair when under extreme duress). Roughly 75% of the film is really Africa, with some footage shot in the U.S. and on MGM’s soundstages in Culver City. When the trio reaches the Mines, for instance, they approach the caves in Africa-shot footage, when they first enter it’s Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, and further into the caves the scene switches to impressive studio sets and backdrops. Yet it’s all so expertly photographed (by Robert Surtees, who won an Oscar), the integration is as seamless as it gets.

Much of Surtees’s footage is remarkable even now. During the stampede, our party huddles behind some low-lying rocks. In a side angle, hundreds of animals leap over them like wayward rockets, footage that doesn’t look like a special effect, but using real animals. Watching these scenes photographed 74 years ago, one can’t help but wonder how many of these wild creatures have since become endangered or even extinct. Likewise, the film, along with Cinerama travelogues made in some of the very same locations soon after, captures indigenous tribes at what must have been the very tail-end of centuries of relative isolation, despite European colonialism, before the encroachment of modern, “civilized” man. Is the Tutsi King’s palace in Nyanza—not designed by MGM art director Cedric Gibbons, as director John Landis asserts in his Trailers from Hell segment on the film—and its surroundings still relatively untouched in 2023, or overrun with 7-Elevens and Starbucks? I wonder.

Dramatically, the film plays well enough that modern audiences not particularly enamored of old movies and/or jungle pictures will likely find the film entertaining. The three leads and the two indigenous supporting parts are appealingly played, and the film is genuinely exciting at times.

Warner Archive’s 4K remastering of King Solomon’s Mines sources the original black-and-white separation camera negatives of this 3-strip Technicolor production. The results are splendiferous—the image is razor-sharp with no matrix bleeding and the color is luxuriously rich. The DTS-HD Master Audio (2.0 mono) is likewise excellent with minimal distortion, despite many “big” scenes of loud action. Optional English subtitles are included on this Region-Free disc.

Extras are limited to, essentially, two trailers, one a standard coming attractions trailer while the other, running just under 10 minutes, is a rare-for-the-time behind the scenes film touting the difficult location shooting and its accompanying complex logistics.

I don’t think I’d seen King Solomon’s Mines since the LaserDisc era; so vastly superior is this new video master in every way that it’s like experiencing the film for the first time. Highly Recommended.

- Stuart Galbraith IV