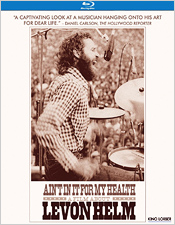

Ain't In It for My Health: A Film About Levon Helm (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Jacob HatleyRelease Date(s)

2010 (October 8, 2013)Studio(s)

Kino Lorber (Kino Lorber)- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: B

- Audio Grade: B

- Extras Grade: A-

Review

On April 18, 2012, Robbie Robertson of The Band confirmed that he had visited his old bandmate Levon Helm in a New York hospital where Helm was fighting terminal cancer: “I sat with Levon for a good while, and thought of the incredible and beautiful times we had together... Levon is one of the most extraordinary talented people I’ve ever known and very much like an older brother to me. I am so grateful I got to see him one last time and will miss him and love him forever.” One day later, Helm died at the age of 71. The long-estranged relationship between Helm, The Band’s drummer, and Robertson, its chief songwriter and guitarist, is never discussed in Jacob Hatley’s 2010 documentary Ain’t In It for My Health: A Film About Levon Helm. But Helm’s unease with his legacy is one of the threads that runs through the film, recently issued on Blu-ray by Kino Lorber.

This frequently-impressionistic film traces days in the life of Helm, the Arkansas-born drummer who brought Southern authenticity to Canadian rockabilly band The Hawks and changed the sound of rock in the process. Once The Hawks broke apart from Ronnie Hawkins, for whom the group was named, they rose to prominence backing Bob Dylan on his 1965 U.S. tour and 1966 world tour. They recorded the storied Basement Tapes with Dylan in 1967 in their home base of Woodstock, New York, and made their own epochal debut as, simply, The Band with 1968’s Music from Big Pink. With Big Pink, The Band returned rock to its stripped-down roots, epitomizing the “Americana” sound and offering an antidote to the bigger and bigger “progressive” sounds appearing on the FM dial. But when Robertson decided to throw in the towel in 1976 – culminating in the San Francisco farewell concert preserved in Martin Scorsese’s 1978 The Last Waltz – Helm, bassist Rick Danko, keyboardist Garth Hudson and pianist Richard Manuel were left adrift. In 1983, The Band reformed sans Robertson, but a dark cloud remained over the group, with Manuel committing suicide in 1986. Danko died in 1999, leading to The Band’s final break-up. And in the late 1990s, Levon Helm was diagnosed with throat cancer, which he successfully treated via intensive radiation treatments. In 2000, he commented to Rolling Stone, “Two things people don’t want – poverty and cancer. And I had them both.” Helm prevailed, at least initially, over the cancer, though his once-strong voice was replaced with a soft rasp. And he prevailed over the poverty by opening up his Woodstock home studio to fans and fellow musicians for informal “Midnight Ramble jam session-style concerts.

It’s important to come into this movie with knowledge of Helm’s, and The Band’s history. Focusing on Helm late in life, it doesn’t recount much of the gifted musician’s life story. The Levon Helm portrayed in Hatley’s film is in the midst of his late-career renaissance. It opens with him making a living on the road, staying at Holiday Inns and smoking joints. (Helm’s friend Bob Dylan’s song “When I Paint My Masterpiece” is heard in one sequence, an ironic composition of perhaps-futile optimism and crushing reality.) Helm speaks with a throaty, plain-spoken drawl, and appears totally at home in Woodstock with his wife Sandy and dog Muddy whether resting or gleefully riding a tractor. Frequently seen with a cigarette of one kind or another in his hand, wearing a bathrobe and an impish grin, Helm is captured by Hatley in more or less his everyday life.

Though only 83 minutes in length, the film is deliberately paced and at times meandering. It follows Helm to the doctor as it chronicles what his daughter, the singer Amy Helm, calls “a different kind of survival story.” Clips of interviewees are interspersed with this fly-on-the-wall footage; Helm’s ex-lover and Amy’s mother Libby Titus (an accomplished vocalist in her own right and wife of Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen) comments, “I don’t know why he’s not dead!” before praising his stamina and hearty Dutch and Irish stock. Danko’s wife Elizabeth, biographer Barney Hoskyns, Helm’s friend and collaborator Larry Campbell, and singer Teresa Williams (Campbell’s wife) all appear. Performance clips are included, too, such as The Band performing “Up on Cripple Creek” in summer 1969 and Robertson’s now-standard “The Weight” that same summer at the Woodstock festival. An amusing clip of “square” Ed Sullivan introducing The Band and stumbling over Levon’s name is another choice segment. Still, footage of the young Helm and his robust appearance shocks in the context of the film.

The tone is generally elegiac, though Helm is a charming and genial subject. There’s some levity when he recalls partying with Procol Harum or reflects on an annoyed Jimi Hendrix backstage at Woodstock. The most dramatic arc in the film revolves around The Grammy Awards. Helm receives a nomination for his solo “comeback” album Dirt Farmer as well as a Lifetime Achievement Award for his role in The Band, but dismisses the latter as “engineered by the suits.” He sits out the ceremony, and the camera captures his reaction when he wins the award for Dirt Farmer. Everybody around Helm seems more excited than he is, as it’s clear that sadness and resentments linger in his back pages. Footage of Helm and Campbell writing and arranging a new song based on an unpublished Hank Williams lyric, “You’ll Never Again Be Mine,” gives the documentary another fascinating through line.

Ain’t In It for My Health is a testament to the late Helm’s indomitable spirit. No matter how cantankerous he may appear, his good humor and upbeat nature inspires. He laments the lack of recognition for the late Manuel and Danko in one of the film’s most touching scenes, and confides in Billy Bob Thornton that “[The Band] was all over after that second record [1969’s The Band].” Hoskyns and Campbell allude to Helm’s bitterness over the fact that Robertson became quite wealthy, as he controlled the publishing to his hit songs, whereas the other Band members struggled. Helm’s fight with financial stability had a silver lining, though, when his Midnight Rambles began in 2003 to raise money to save his home. Not only did the Rambles give Helm a new lease on life, as shown in the film, but he also became a grandfather with the birth of Amy’s son, whom he serenades on mandolin in one beautiful moment.

The 1:85:1 color film looks about as good as could be expected on Kino’s 1080p BD, though much of the archival footage naturally doesn’t impress. Audio is offered in both 5.1 surround and 2.0 stereo options, and though the former is preferable, the rear channels are only utilized sparingly, such as for occasional ambience. No subtitles are available. A whopping 50 minutes of deleted scenes is a most welcome bonus. You’ll also find the original trailer here.

Though Helm perished when his cancer recurred, the intermittently captivating and altogether affectionate Ain’t In It for My Health depicts a true rock-and-roll survivor surrounded by loving family and friends. It should leave viewers with relief that Helm finally “took a load off,” with an immense “Weight” removed. At one point in the film he stresses the importance of “how we live” – not just how long. Jacob Hatley’s film certainly shows that the great Levon Helm knew how to live.

- Joe Marchese