“Jaws was something of an accidental blockbuster. It should not be blamed for being a good movie.” — Joseph McBride

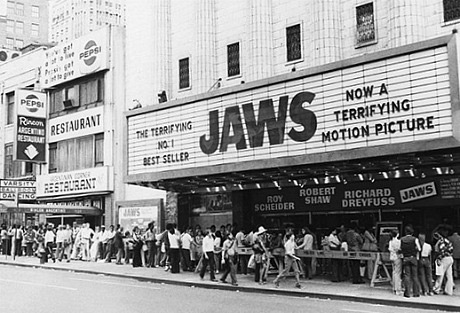

The Digital Bits is pleased to present this retrospective commemorating the 40th anniversary of the release of Jaws, Steven Spielberg’s legendary tale of a Great White preying on a coastal New England resort community during the lucrative summer tourism season.

Based upon Peter Benchley’s best-selling novel and starring Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw and Richard Dreyfuss, Jaws shattered all existing box-office records, scared the wits out of beachgoers, and became every studio’s dream model of a summer blockbuster (and, in some circles, a whipping boy for popular, successful movies). [Read on here…]

The Digital Bits celebrates the occasion with this article presenting the usual collection of features Bits readers have to come to expect from the History, Legacy & Showmanship column: a compilation of box-office data that places the performance of Jaws in context, noteworthy passages from vintage film reviews, production and exhibition information, a list of the theaters that played the movie upon its initial release, and, finally, an interview segment with a group of historians and documentary filmmakers who discuss the attributes of Jaws and examine why it and Spielberg have endured.

NUMBER$

*Established new industry record

- 1 = Rank on all-time list of top-grossing films at close of run*

- 1 = Rank on all-time list of top rentals at close of run*

- 1 = Rank on top-grossing films of 1975

- 2 = Number of years holding #1 spot on list of all-time top-grossing films

- 3 = Number of Academy Awards

- 4 = Number of Academy Award nominations

- 7 = Number of years Universal Pictures’ most-successful film

- 7 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing films (adjusted for inflation)

- 9 = Number of consecutive weeks it was the nation’s top-grossing film

- 14 = Number of days to turn a profit

- 26 = Steven Spielberg’s age when he was offered the directorial assignment

- 43 = Number of weeks longest-running engagement played

- 48 = Rank on American Film Institute’s list of the 100 Greatest American Films

- 59 = Number of days it took to surpass $100 million*

- 78 = Number of days it took to become the industry’s top-grossing movie

- 78 = Rank on current list of all-time top-grossing films

- 159 = Number of days it took to shoot the movie

- 161 = Number of days it took to surpass $150 million*

- 464 = Number of opening-week bookings

- 2,460 = Number of bookings during first six months of release

- $175,000 = Amount paid to acquire motion picture rights

- $2.5 million = Amount Universal spent on marketing in advance of its release

- $3.0 million = Salary plus profit-participation earned by Spielberg

- $7.1 million = Opening-weekend box-office gross*

- $9.0 million = Production cost

- $11.7 million = Box-office rental (1979 re-release)

- $16.0 million = Box-office rental (1976 re-release)

- $21.1 million = Box-office gross for first ten days of release*

- $39.8 million = Production cost (adjusted for inflation)

- $102.7 million = Box-office rental (as of January 1, 1976)*

- $118.7 million = Box-office rental (as of January 1, 1977)*

- $121.4 million = Box-office rental (as of January 1, 1978)

- $133.4 million = Box-office rental (as of January 1, 1980)

- $192.0 million = Box-office gross (original release)

- $210.7 million = International box-office gross (original + re-releases)

- $260.0 million = Box-office gross (original + re-releases)

- $470.7 million = Worldwide box-office gross (original + re-releases)

- $1.1 billion = Cumulative domestic box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

- $2.1 billion = Cumulative worldwide box-office gross (adjusted for inflation)

A SAMPLING OF MOVIE REVIEWER QUOTES:

“Jaws is an artistic and commercial smash. Producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown, and director Steven Spielberg, have the satisfaction of a production problem-plagued film turning out beautifully. Peter Benchley’s bestseller about a killer shark and a tourist beach town has become a film of consummate suspense, tension and terror. The Universal release looks like a torrid moneymaker everywhere.” — A.D. Murphy, Variety

“It is news when a 26-year-old film director goes $2 million over budget and two and a half months over schedule and manages to avoid getting fired. But then, Steven Spielberg has managed to perform the impossible for most of his brief adult life—like successfully directing Joan Crawford in her first television movie. His most recent accomplishment will be hard to beat.” — Bob Thomas, Associated Press

“Destined to become a classic.” — Arthur Cooper, Newsweek

“The first and crucial thing to say about the movie Universal has made from Peter Benchley’s best-seller Jaws is that the PG rating is grievously wrong and misleading. The studio has rightly added its own cautionary notices in the ads, and the fact is that Jaws is too gruesome for children, and likely to turn stomachs of the impressionable at any age.” — Charles Champlin, Los Angeles Times

“The first and crucial thing to say about the movie Universal has made from Peter Benchley’s best-seller Jaws is that the PG rating is grievously wrong and misleading. The studio has rightly added its own cautionary notices in the ads, and the fact is that Jaws is too gruesome for children, and likely to turn stomachs of the impressionable at any age.” — Charles Champlin, Los Angeles Times

“It is a study in stress, and as effective a film as has ever been made.” — John Wasserman, San Francisco Chronicle

“Jaws—maybe the scariest film ever.” — Jeanne Miller, San Francisco Examiner

“Brilliant young director Steven Spielberg has taken the premise of Peter Benchley’s best-selling but rather pedestrian novel Jaws—a summer resort community terrorized by the presence of a rogue Great White Shark—and streamlined it into a new classic of cinematic horror and high adventure. The movie version of Jaws is one of the most exciting and satisfying thrillers ever made.” — Gary Arnold, The Washington Post

“Jaws is a thriller of surprise rather than suspense. You feel like a rat, being given shock treatment, who has not yet figured out the pattern.” — Molly Haskell, The Village Voice

“The real hero of the film is young director Steven Spielberg. No review of Jaws should tell you too much of what happens, but every review of Jaws should tell you how masterfully Spielberg manipulates the audience. Wisely he relies on our imagination. For a long time we don’t see the whole shark, just the results. Or we are the shark, hovering beneath the swimmers, watching.” — Dominique Paul Noth, The Milwaukee Journal

“Jaws is not only a pre-sold smash, but a superbly crafted motion picture. Benchley’s lumbering, trashy but undeniably exciting novel has been cut to its narrative bone, leaving a tale of horror and adventure so gripping that one quickly becomes grateful to Spielberg and his cast for leavening it with regular doses of humor.” — John Hartl, The Seattle Times

“Approaching the horror film genre, Jaws is essentially a suspense and adventure film that blends an attractive and competent cast with the sure-handed direction of Spielberg.” — John Anders, The Dallas Morning News

“There’s a pretty fair novel called Jaws that someone should turn into a movie some day. The current movie of the same name bears little relationship to the book, and is just another horror-action picture in which personal revelation plays no part. It is merely three madmen against a huge shark and gives no feeling that these people have any existence apart from the movie.” — Emerson Batdorff, The (Cleveland) Plain Dealer

“In spite of some rather gruesome scenes, Jaws is a superior piece of entertainment.” — Larry Stallings, Daytona Beach Journal

“Jaws is a movie whose every shock is a devastating surprise. It is elaborate, technically intricate, and wonderfully crafted. Contains classic sequences of suspense…The final battle is literally explosive.” — Time

“[W]hat this movie is about, and where it succeeds best, is the primordial level of fear. The characters, for the most part, and the nonfish elements in the story, are comparatively weak and not believable…. The three men in the tub who go hunting the shark are played to varying levels of competence by Roy Scheider (Gene Hackman’s partner in The French Connection) as the police chief, Richard (Duddy Kravitz), Dreyfuss as the young fish expert, and Robert Shaw (the conned con man in The Sting) as the grizzled, Ahab-style shark hunter. Because these actors have delivered strong performances in many other films, I’m inclined to fault the casting and dialog for their varying degrees of believability.” — Gene Siskel, Chicago Tribune

“Shock piles upon shock until the viewer is half-dead from fright, and it’s all so skillfully directed by 27-year-old Steven Spielberg, edited by Verna Fields, scored by John Williams and photographed by Bill Butler, that you can’t escape its tension and power even if you want to.” — Rex Reed, New York Daily News

“Jaws provides us with chills enough for the hottest of summers and hydrophobia for life.” — Judith Crist, New York Magazine

“The moment the shark appears, displaying the most destructive set of dentures ever, [the movie] has a lot of bite. From its beginning at the nightmarish beach party to the later daylight terror, Jaws is a movie that will draw oohs and aahs and perhaps retire bathing suits.” — James Meade, The San Diego Union

“If you think about Jaws for more than 45 seconds you will recognize it as nonsense, but it’s the sort of nonsense that can be a good deal of fun if you like to have the wits scared out of you at irregular intervals.” — Vincent Canby, The New York Times

“Spielberg ranks with [William] Friedkin as a foremost commercial practitioner of a gritty, punchy, visual equivalent of best-seller prose.” — Tom Allen, The Village Voice

“The technical credits, from Bill Butler’s photography to John Williams’ music, with a theme that recalls Bernard Herrmann’s classic score for Psycho, all add up to movie magic of a high order.” — George Anderson, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

THE ORIGINAL ENGAGEMENTS:

Listed below are the theaters in the United States and Canada that opened Jaws on June 20th, 1975. These were the only theaters, with a few exceptions, that showed the movie during its first few weeks of release. (A few additional bookings and some non-traditional rotational bookings in coastal resort regions opened the movie in between the June 20th first wave and the July 25th second wave.) Contrary to numerous historical accounts, the number of theaters in which Jaws opened was not an industry record.

The duration of the engagements, measured in weeks, has been included in parenthesis after most of the entries.

During its sixth week, the release of Jaws was expanded by about 200 bookings, with additional bookings added weekly throughout the summer and into autumn and winter. By the end of the movie’s lengthy run it had played more than 2,000 engagements (plus hundreds more internationally). The film’s subsequent-wave, international and re-release bookings have not been included in the list below.

ALABAMA

- Birmingham — Cobb’s Village East Twin (26 weeks)

- Decatur — United Amusement’s Gateway Twin (14)

- Huntsville — Martin’s Westbury Cinerama (15)

- Mobile — Giddens & Rester’s Airport Twin (22)

- Montgomery — Martin’s Martin Twin (15)

ALASKA

No theaters in Alaska played Jaws during Release Wave #1

ALBERTA

- Calgary — 17th Avenue Drive-In (13)

- Calgary — Odeon’s Grand Twin (23)

- Edmonton — Odeon’s Rialto Twin (27)

- Edmonton — Sky-Vue Drive-In (16)

- Lethbridge — Famous Players’ Paramount (8)

- Red Deer — Famous Players’ Paramount Twin (8)

ARIZONA

- Phoenix — United Artists’ Chris-Town Mall 6 (36)

- Scottsdale — Nace’s Round-Up Drive-In (22)

- Tucson — Mann’s Park Mall 4 (42)

ARKANSAS

- Fort Smith — American Multi-Cinema’s Phoenix Village Twin (15)

- North Little Rock — General Cinema Corporation’s McCain Mall Cinema I & II (16)

BRITISH COLUMBIA

- New Westminster — Odeon’s Odeon (15)

- Prince George — Odeon’s Princess (9)

- Surrey — Odeon’s Surrey Drive-In (16)

- Vancouver — Odeon’s Vogue (18)

- Victoria — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (15)

- West Vancouver — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (13)

CALIFORNIA

- Anaheim — Vinstrand’s Brookhurst (20)

- Bakersfield — American Multi-Cinema’s Stockdale 6 (#1: 22)

- Bakersfield — American Multi-Cinema’s Stockdale 6 (#2: 12)

- Buena Park — Pacific’s Buena Park Drive-In (16)

- Burlingame — Syufy’s Hyatt Twin (27)

- Carlsbad — Sanborn’s Cinema Plaza 4 (18)

- City of Industry — Pacific’s Vineland Drive-In (13)

- Concord — Syufy’s Solano Drive-In (15)

- Costa Mesa — Edwards’ Cinema (17)

- Culver City — Pacific’s Studio Drive-In (10)

- Daly City — United Artists’ Serra (26)

- Fresno — Lippert’s Country Squire (15)

- Gardena — Pacific’s Vermont Drive-In (10)

- Highland — Pacific’s Baseline Drive-In (13)

- Isla Vista — Metropolitan’s Magic Lantern Twin (#1: 17)

- Isla Vista — Metropolitan’s Magic Lantern Twin (#2: 14)

- La Habra — American Multi-Cinema’s Fashion Square 4 (27)

- La Mesa — Mann’s Alvarado Drive-In (27)

- Lakewood — Pacific’s Lakewood Center 4 (19)

- Long Beach — Pacific’s Los Altos 3-Screen Drive-In (10)

- Los Angeles (Canoga Park) — Century’s Holiday (19)

- Los Angeles (Century City) — Plitt’s Century Plaza Twin (17)

- Los Angeles (Hollywood) — Pacific’s Pix (19)

- Los Angeles (Panorama City) — Lippert’s Americana 6 (#1: 19)

- Los Angeles (Panorama City) — Lippert’s Americana 6 (#2: 19)

- Los Angeles (Van Nuys) — Pacific’s Sepulveda Drive-In (13)

- Mill Valley — Cinerama’s Sequoia Twin (19)

- Monterey — Kindair’s Steinbeck (15)

- Oakland — Cinerama’s Piedmont (26)

- Oxnard — Mann’s Esplanade Triplex (19)

- Palm Springs — Metropolitan’s Plaza (15)

- Paramount — Pacific’s Rosecrans Drive-In (10)

- Pasadena — Mann’s Hastings Triplex (19)

- Pleasant Hill — Syufy’s Century 25 (27)

- Redondo Beach — General Cinema Corporation’s South Bay Cinema I-II-III-IV (27)

- Redwood City — Syufy’s Redwood 4-Screen Drive-In (15)

- Riverside — United Artists’ Tyler Mall Cinema 4 (19)

- Sacramento — Syufy’s Century 24 (27)

- Sacramento — Syufy’s Sacramento 5-Screen Drive-In (20)

- San Diego — American Multi-Cinema’s Fashion Valley 4 (#1: 27)

- San Diego — American Multi-Cinema’s Fashion Valley 4 (#2: 27)

- San Francisco — United Artists’ Coliseum (26)

- San Jose — Syufy’s Century 24 Twin (38)

- San Leandro — Plaza Twin (27)

- South San Francisco — Syufy’s Spruce 2-Screen Drive-In (15)

- Stockton — General Cinema Corporation’s Sherwood Plaza Cinema I & II (20)

- Union City — Syufy’s Union City 3-Screen Drive-In (21)

- Ventura — Pacific’s 101 3-Screen Drive-In (10)

- West Covina — Sanborn’s Wescove Twin (27)

COLORADO

- Boulder — United Artists’ Regency (17)

- Colorado Springs — Commonwealth’s Rustic Hills North Twin (27)

- Denver — Cooper-Highland’s Cooper (27)

- Fort Collins — Commonwealth’s Campus West (16)

CONNECTICUT

- Danbury — Brandt’s Cine (9)

- Darien — United Artists’ Darien Playhouse (14)

- Greenwich — Trans-Lux’s Plaza (9)

- Groton — United Artists’ Groton (14)

- Hamden — Whitney (13)

- Manchester — United Artists’ Theatres East Triplex (19)

- Milford — General Cinema Corporation’s Milford Cinema I & II (16)

- Newington — General Cinema Corporation’s Newington Cinema I & II (16)

- Trumbull — United Artists’ Trumbull (10)

- Waterbury — General Cinema Corporation’s Naugatuck Valley Mall Cinema I-II-III (16)

- West Hartford — United Artists’ The Movies at Westfarms Triplex (20)

- Westport — Brandt’s Post (9)

DELAWARE

- Rehoboth Beach — Midway Enterprises’ Midway Palace Twin

- Wilmington — Brandt’s Edgemoor (15)

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

- Washington — General Cinema Corporation’s Jenifer Cinema I & II (18)

FLORIDA

- Altamonte Springs — General Cinema Corporation’s Altamonte Mall Cinema I & II (19)

- Bradenton — CinemaNational’s DeSoto Square Mall 4 (14)

- Clearwater — ABC Florida State’s Capitol (14)

- Coral Gables — Wometco’s Miracle (21)

- Daytona Beach — General Cinema Corporation’s Bellair Plaza Cinema I & II (20)

- Deerfield Beach — South Florida’s Gold Coast Drive-In (15)

- Fort Lauderdale — Gulf States’ Village Triplex

- Fort Myers — ABC Florida State’s Arcade (13)

- Fort Walton Beach — Gulf States’ Brooks Plaza Triplex (13)

- Gainesville — Eastern Federal’s Royal Park 4 (15)

- Hollywood — Wometco’s Plaza Twin (16)

- Jacksonville — ABC Florida State’s Regency Twin (20)

- Lakeland — General Cinema Corporation’s Imperial Mall Cinema I & II (17)

- Lauderhill — General Cinema Corporation’s Lauderhill (15)

- Merritt Island — General Cinema Corporation’s Merritt Cinema I & II (15)

- North Miami Beach — General Cinema Corporation’s 170th Street (15)

- North Palm Beach — Budco’s Twin City (13)

- Orlando — ABC Florida State’s Plaza Twin (19)

- Panama City — Martin’s Capri (13)

- Pensacola — Giddens & Rester’s Cordova Twin (16)

- St. Petersburg — ABC Florida State’s Plaza Twin (19)

- Sarasota — ABC Florida State’s Plaza Twin (13)

- Tallahassee — Eastern Federal’s Miracle Twin (13)

- Tampa — ABC Florida State’s Hillsboro Twin (18)

- Tampa — General Cinema Corporation’s University Square Mall Cinema I-II-III-IV (18)

- West Palm Beach — General Cinema Corporation’s Cinema 70 (17)

GEORGIA

- Atlanta — ABC Southeastern’s Phipps Plaza Triplex (27)

- Augusta — ABC Southeastern’s Imperial (15)

- Jonesboro — Weis’ Arrowhead Cinema Centre Triplex (23)

- Macon — Weis’ Cinema Centre Triplex (16)

- Savannah — Weis’ Cinema Centre Triplex (16)

- Smyrna — Georgia Theatre Company’s Belmont (17)

HAWAII

- Honolulu — Consolidated’s Waikiki Twin (16)

IDAHO

- Boise — Plitt’s Midway Drive-In (17)

- Idaho Falls — Rio (14)

ILLINOIS

- Aurora — L & M’s West Plaza Twin (14)

- Champaign — Kerasotes’ Orpheum (15)

- Chicago — General Cinema Corporation’s Ford City Cinema I-II-III (26)

- Chicago — Plitt’s Gateway (26)

- Chicago — Plitt’s United Artists (24)

- DeKalb — CinemaNational’s Cinema Twin (14)

- Joliet — Mode (14)

- Lombard — General Cinema Corporation’s Yorktown Cinema I & II (25)

- Milan — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 6 (18)

- Niles — Fink & Fink’s Golf Mill Triplex (26)

- Peoria — Mann’s Fox (19)

- Rockford — Plitt’s Midway (16)

- Springfield — Kerasotes’ Capital City (21)

- Waukegan — Plitt’s Genesee (15)

INDIANA

- Anderson — General Cinema Corporation’s Mounds Mall Cinema I & II (13)

- Elkhart — Kerasotes’ Concord Twin

- Evansville — Mid-States’ North Park Twin (27)

- Fort Wayne — General Cinema Corporation’s Northwood Cinema I & II (20)

- Greenwood — General Cinema Corporation’s Greenwood Cinema I-II-III (18)

- Indianapolis — General Cinema Corporation’s Glendale Cinema I-II-III-IV (25)

- Indianapolis — General Cinema Corporation’s Washington Square Cinema I & II (19)

- Kokomo — General Cinema Corporation’s Kokomo Mall Cinema I-II-III (12)

- Lafayette — Lafayette

- Muncie — General Cinema Corporation’s Northwest Plaza Cinema I & II (20)

- South Bend — Plitt’s Scottsdale (14)

- Terre Haute — General Cinema Corporation’s Honey Creek Square Cinema I & II (15)

IOWA

- Cedar Rapids — Dubinsky’s Eastown Twin (22)

- Des Moines — Dubinsky’s Fleur 4 (20)

- Des Moines — Dubinsky’s Forum 4 (27)

- Dubuque — General Cinema Corporation’s Kennedy Mall Cinema I & II (12)

- Sioux City — Dubinsky’s Plaza Twin (20)

- Waterloo — Cinema Entertainment Corporation’s Crossroads Twin (15)

KANSAS

- Lawrence — Commonwealth’s Hillcrest Triplex (15)

- Salina — Dickinson’s Mid-State Twin (14)

- Topeka — General Cinema Corporation’s Topeka Boulevard Cinema I & II (14)

- Wichita — American Entertainment’s Cinemas East 4 (30)

KENTUCKY

- Lexington — General Cinema Corporation’s Fayette Mall Cinema I & II (18)

- Louisville — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 6 (27)

LOUISIANA

- Alexandria — General Cinema Corporation’s Alexandria Mall Cinema I & II (13)

- Baton Rouge — Gulf States’ University Cinema 4 (33)

- Lafayette — Ogden-Perry’s Center Twin (15)

- Lake Charles — Ogden-Perry’s Charles Triplex (13)

- New Orleans — Joy’s Joy (27)

- Shreveport — Joy’s Cinema City 6 (#1: 20)

- Shreveport — Joy’s Cinema City 6 (#2: 10)

- West Monroe — McMillan Twin (18)

MAINE

- Brewer — Cinema Centers’ Brewer Cinema Center Triplex (23)

- Portland — E.M. Loew’s Fine Arts Twin (15)

- Waterville — Sonderling Broadcasting Corporation’s Cinema Center 4 (15)

MANITOBA

- Winnipeg — Famous Players’ Airliner Drive-In (12)

- Winnipeg — Famous Players’ Capitol (16)

MARYLAND

- Annapolis — Durkee’s Circle (13)

- Baltimore — Durkee’s Senator (17)

- Catonsville — Westview 4 (17)

- Dundalk — Strand (12)

- Frederick — Interstate’s Frederick Towne Mall Twin (9)

- Hagerstown — Jack Fruchtman’s Cinema Twin (15)

- Ocean City — Schwartz’s Surf Twin

- Randallstown — Durkee’s Liberty Twin (12)

- Riverdale — District’s Riverdale Plaza (27)

- Wheaton — Aspen Hill Twin (23)

MASSACHUSETTS

- Boston — Walter Reade’s Charles Triplex (22)

- Brockton — General Cinema Corporation’s Westgate Mall Cinema I-II-III-IV (15)

- Burlington — General Cinema Corporation’s Burlington Mall Cinema I & II (20)

- Danvers — Sack’s Cinema City 4 (16)

- Dedham — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 3 (15)

- Fall River — Interstate’s Center Twin (9)

- Framingham — General Cinema Corporation’s Shoppers World Cinema I-II-III-IV (15)

- Hanover — General Cinema Corporation’s Hanover Mall Cinema I-II-III-IV (22)

- Hyannis — Interstate’s Cape Cod Mall

- Lawrence — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 4 (15)

- Mashpee — Seabury Twin

- North Dartmouth — General Cinema Corporation’s North Dartmouth Mall Cinema I-II-III-IV (15)

- Oak Bluffs — Island

- Pittsfield — Paris (16)

- Plymouth — Cinema Twin (12)

- Provincetown — New Art

- West Springfield — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 6 (17)

- Worcester — Redstone’s Cinema 1 at Webster Square (19)

MICHIGAN

- Ann Arbor — Butterfield’s State (14)

- Bay City — Butterfield’s State (9)

- Benton Harbor — CinemaNational’s Fairplain Twin (15)

- Detroit — Suburban Detroit Vogue (17)

- Flint — Butterfield’s Genesee Valley Twin (31)

- Grand Rapids — Loeks’ Alpine Twin (43)

- Jackson — CinemaNational’s Westwood Twin (15)

- Lansing — Plitt’s Mall (19)

- Livonia — Nicholas George’s Mai Kai (27)

- Portage — Loeks’ Plaza Twin (24)

- Roseville — General Cinema Corporation’s Macomb Mall Cinema I & II (26)

- Saginaw — General Cinema Corporation’s Green Acres (16)

- Southfield — Nicholas George’s Americana 4 (27)

- Southgate — Nicholas George’s Southgate Triplex (27)

- Sterling Heights — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas 5 (20)

- Waterford — General Cinema Corporation’s Pontiac Mall Cinema I & II (19)

MINNESOTA

- Duluth — Cinema Entertainment Corporation’s Kenwood Twin (16)

- Minneapolis — Berger Amusement’s Gopher (27)

- White Bear Lake — Carisch’s Cine Capri (33)

MISSISSIPPI

- Biloxi — Gulf States’ Surfside Twin (13)

- Hattiesburg — Gulf States’ Avanti (20)

- Jackson — Ogden-Perry’s Ellis Isle Twin (16)

MISSOURI

- Columbia — Commonwealth’s Uptown (17)

- Creve Coeur — Wehrenberg’s Creve Coeur (17)

- Florissant — General Cinema Corporation’s Grandview (17)

- Joplin — Dickinson’s Eastgate Triplex (19)

- Kansas City — American Multi-Cinema’s Midland Triplex (26)

- Mehlville — General Cinema Corporation’s South County (17)

- St. Louis — Arthur Enterprises’ Stadium I (17)

MONTANA

No theaters in Montana played Jaws during Release Wave #1

NEBRASKA

- Lincoln — Cooper-Highland’s Plaza 4 (#1: 14)

- Lincoln — Cooper-Highland’s Plaza 4 (#2: 14)

- Omaha — Cooper-Highland’s Indian Hills (17)

NEVADA

- Las Vegas — Cragin’s Red Rock 11 (26)

- Reno — United Artists’ Granada Twin (18)

NEW BRUNSWICK

- Moncton — Odeon’s Capitol (14)

- Saint John — Famous Players’ Plaza (9)

NEW HAMPSHIRE

- Bedford — General Cinema Corporation’s Bedford Mall Cinema I & II

- Nashua — General Cinema Corporation’s Nashua Mall Cinema I & II (9)

- Portsmouth — Jerry Lewis Twin (16)

NEW JERSEY

- Beach Haven — Colonial

- Berkeley Township — Music Makers’ Berkeley Twin (14)

- Brick Township — Tri State’s Circle Twin (19)

- Cherry Hill — Budco’s Ellisburg (13)

- East Brunswick — United Artists’ Turnpike Twin (15)

- Edison — United Artists’ Plainfield Drive-In (14)

- Fair Lawn — United Artists’ Hyway (18)

- Freehold — Triangle’s Pond Road (16)

- Hackensack — United Artists’ Fox (18)

- Hazlet — United Artists’ Hazlet Twin (18)

- Jersey City — General Cinema Corporation’s Hudson Plaza Cinema I & II (18)

- Long Branch — Grant’s The Movies Twin (14)

- Maplewood — Triangle’s Maplewood (16)

- Montclair — Clairidge (22)

- Ocean City — Shriver’s Village (5)

- Parsippany — General Cinema Corporation’s Morris Hills Cinema I & II (18)

- Pleasantville — Frank’s Towne 4 (26)

- Princeton — Garden (16)

- South Plainfield — United Artists’ Cinema (18)

- Vineland — Budco’s Vineland Twin

- Wayne — United Artists’ Wayne (18)

- Westfield — United Artists’ Rialto (18)

- Wildwood — Hunt’s Blaker (12)

- Willingboro — SamEric’s Twin Willingboro (19)

NEW MEXICO

- Albuquerque — Commonwealth’s Cinema East Twin (27)

NEW YORK

- Amherst — General Cinema Corporation’s Boulevard Mall Cinema I-II-III (16)

- Bay Shore — United Artists’ Bay Shore (18)

- Big Flats — General Cinema Corporation’s On the Mall Cinema I & II

- Bronxville — United Artists’ Cinema (18)

- Cheektowaga — Holiday’s Holiday 6 (27)

- Coram — United Artists’ Coram Drive-In (14)

- East Hampton — United Artists’ East Hampton (3)

- Endicott — Cinema

- Floral Park — Century’s Floral (18)

- Hauppauge — Creative’s Hauppauge (21)

- Henrietta — General Cinema Corporation’s Todd Mart Cinema I & II (27)

- Hicksville — United Artists’ Hicksville (18)

- Huntington — Century’s Shore Twin (18)

- Latham — United Artists’ Towne (23)

- Middletown — CinemaNational’s Cinema (14)

- Monticello — General Cinema Corporation’s Mall Cinema I & II (11)

- New City — United Artists’ Cinema 304 (15)

- New Hartford — CinemaNational’s Cinema (18)

- New York (Bronx) — United Artists’ Capri (21)

- New York (Brooklyn) — Century’s Kings Plaza Twin (18)

- New York (Brooklyn) — Century’s Rialto (18)

- New York (Brooklyn) — United Artists’ Marboro (18)

- New York (Manhattan) — Loews’ Orpheum (16)

- New York (Manhattan) — United Artists’ Rivoli (22)

- New York (Manhattan) — Walter Reade’s 34th Street East (18)

- New York (Queens) — Century’s Prospect (18)

- New York (Queens) — United Artists’ Astoria (14)

- New York (Queens) — United Artists’ Lefrak (18)

- New York (Staten Island) — United Artists’ Island Twin (18)

- Ossining — General Cinema Corporation’s Arcadian Cinema I & II (12)

- Patchogue — United Artists’ Patchogue (14)

- Pearl River — Pearl River (14)

- Peekskill — Lesser’s Beach Triplex (9)

- Plattsburgh — Cinema Centers’ Pyramid Mall Twin (12)

- Poughkeepsie — CinemaNational’s Dutchess (18)

- Queensbury — Cinema Centers’ Route 9 Triplex

- Syracuse — CinemaNational’s Shop City (27)

- Valley Stream — Century’s Green Acres (18)

- Wantagh — Mann’s Wantagh (18)

- White Plains — United Artists’ Cinema (18)

NEWFOUNDLAND

- St. John’s — Famous Players’ Capitol (5)

NORTH CAROLINA

- Asheville — Irvin-Fuller’s Merrimon Twin (17)

- Charlotte — ABC Southeastern’s Tryon Mall Twin (18)

- Durham — Martin’s Yorktowne Twin (14)

- Fayetteville — Consolidated’s Bordeaux Twin (19)

- Greensboro — ABC Southeastern’s Terrace Twin (16)

- Raleigh — Martin’s Village Twin (16)

- Wilmington — Stewart & Everett’s Bailey (9)

- Winston-Salem — Martin’s Parkview Twin (15)

NORTH DAKOTA

- Fargo — Cinema Entertainment Corporation’s Cinema 70 (17)

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

No theaters in Northwest Territories played Jaws during Release Wave #1

NOVA SCOTIA

- Dartmouth — Famous Players’ Penhorn Mall Triplex (8)

- Halifax — Famous Players’ Paramount Twin (15)

OHIO

- Akron — General Cinema Corporation’s Chapel Hill Cinema I-II-III (27)

- Canton — General Cinema Corporation’s Mellett Mall Cinema I & II (20)

- Cincinnati — Mid-States’ Northgate 5 (27)

- Cincinnati — Mid-States’ Skywalk Twin (27)

- Cincinnati — Mid-States’ Valley Twin (17)

- Cleveland Heights — Rappaport’s Severance Twin (26)

- Columbus — General Cinema Corporation’s University City (20)

- Dayton — Chakeres’ Dayton Mall 2 (21)

- Elyria — National’s Midway Twin (16)

- Fairview Park — National’s Fairview Twin (21)

- Mentor — General Cinema Corporation’s Mentor Mall Cinema I-II-III (27)

- Niles — National’s Eastwood Twin (17)

- Ontario — General Cinema Corporation’s Richland Mall Cinema I & II (15)

- Parma — General Cinema Corporation’s Parmatown Cinema I-II-III (27)

- Springdale — Mid-States’ Princeton Twin (20)

- Springfield — Chakeres’ State (9)

- Steubenville — Cinemette’s Cinema Hollywood Plaza (14)

- Toledo — Redstone’s Showcase Cinemas Triplex (26)

- Trotwood — Levin’s Kon-Tiki Twin (20)

- Whitehall — Sugarman’s Cinema East (20)

- Youngstown — Cinemette’s Uptown (17)

OKLAHOMA

- Lawton — Video Independent’s Video Twin (14)

- Oklahoma City — Oklahoma Cinema’s North Park 4 (18)

- Tulsa — General Cinema Corporation’s Southroads Mall (21)

ONTARIO

ONTARIO

- Belleville — Odeon’s Quinte Mall Twin (12)

- Brampton — Odeon’s Odeon (15)

- Brantford — Odeon’s Odeon (9)

- Burlington — Odeon’s Odeon (15)

- Concord — Odeon’s Dufferin Drive-In (15)

- Hamilton — Odeon’s Hamilton Drive-In (10)

- Hamilton — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (14)

- Kingston — Odeon’s Odeon (8)

- Kitchener — Odeon’s Odeon (16)

- Kitchener — Odeon’s Parkway Drive-In (10)

- London — Mustang Drive-In (9)

- London — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (12)

- Mississauga — Odeon’s Sheridan Twin (16)

- North Bay — Odeon’s Odeon (9)

- Oshawa — Odeon’s Plaza (12)

- Ottawa — Famous Players’ Airport Drive-In (14)

- Ottawa — Famous Players’ Nelson (19)

- Peterborough — Odeon’s Odeon (10)

- Pickering — Odeon’s Bay Ridges Drive-In (10)

- Sarnia — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (12)

- St. Catharines — Odeon’s Lincoln (16)

- Sault Ste. Marie — Odeon’s Odeon (8)

- Scarborough — Odeon’s Elane (19)

- Sudbury — Odeon’s Odeon Twin (12)

- Thunder Bay — Odeon’s Victoria (10)

- Toronto — Odeon’s Albion Twin (20)

- Toronto — Odeon’s Hyland Twin (27)

- Windsor — Odeon’s Odeon (13)

OREGON

- Beaverton — Moyer’s Town Center Tri-Cinema (26)

- Eugene — Moyer’s West 11th Tri-Cinema (24)

- Milwaukie — Luxury Theatres’ Southgate Quad (27)

- Portland — Luxury Theatres’ Foster Tri-Drive-In (27)

- Salem — Luxury Theatres’ Lancaster Mall Quad (27)

PENNSYLVANIA

- Camp Hill — United Artists’ Camp Hill Twin (16)

- Chester — SamEric’s Twin West Goshen (19)

- Erie — Cinemette’s Strand (19)

- Fairless Hills — SamEric’s U.S. #1 North Drive-In (19)

- Feasterville — SamEric’s Feasterville (17)

- Glenolden — SamEric’s MacDade Mall (19)

- Harrisburg — Union Deposit Twin (18)

- Horsham Township — SamEric’s Twin Horsham (18)

- Johnstown — Richland Mall Twin (17)

- Lancaster — Budco’s Wonderland Twin (18)

- Monaca — General Cinema Corporation’s Beaver Valley Mall Cinema I-II-III (20)

- Montgomeryville — Budco’s 309 Drive-In (13)

- Philadelphia — Budco’s City Line Center Twin (13)

- Philadelphia — Budco’s Goldman Twin (18)

- Philadelphia — Merben (19)

- Pittsburgh — Cinemette’s Gateway (18)

- Plymouth Meeting — General Cinema Corporation’s Plymouth (13)

- Scranton — General Cinema Corporation’s Viewmont Mall Cinema I-II-III (17)

- Wayne — Budco’s Mainline Drive-In

- Whitehall — Budco’s Plaza (16)

- Wilkes-Barre — General Cinema Corporation’s Wyoming Valley Mall Cinema I & II (18)

- Wyomissing — United Artists’ Berkshire Mall (18)

- York — United Artists’ Delco Plaza Mall Triplex

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND

No theaters in Prince Edward Island played Jaws during Release Wave #1

QUEBEC

- Dorval — United’s Dorval Twin (12)

- Greenfield Park — United’s Greenfield Park Twin (16)

- Laval — United’s Laval Twin (16)

- Montreal — United’s Kent (12)

- Montreal — United’s Loew’s (13)

RHODE ISLAND

- Warwick — General Cinema Corporation’s Warwick Mall Cinema I & II (16)

- Westerly — Interstate’s Westerly Twin

SASKATCHEWAN

- Regina — Odeon’s Centre (12)

- Saskatoon — Famous Players’ Capitol (12)

SOUTH CAROLINA

- Columbia — Irvin-Fuller’s Dutch Square Twin (19)

- Greenville — Martin’s Astro Twin (17)

- North Charleston — ABC Southeastern’s Terrace (15)

- Spartanburg — Irvin-Fuller’s Hillcrest Twin (15)

SOUTH DAKOTA

No theaters in South Dakota played Jaws during Release Wave #1

TENNESSEE

- Chattanooga — ABC Southeastern’s Eastgate Twin (15)

- Goodlettsville — Martin’s Rivergate 4 (19)

- Knoxville — ABC Southeastern’s Studio One (19)

- Memphis — Southern Theatre Service’s Park (26)

- Nashville — Martin’s Green Hills (19)

TEXAS

- Abilene — ABC Interstate’s Westwood (12)

- Amarillo — General Cinema Corporation’s Western Plaza Cinema I & II (17)

- Arlington — American Multi-Cinema’s Forum 6 (27)

- Austin — General Cinema Corporation’s Highland Mall Cinema I & II (17)

- Beaumont — Gulf States’ Gaylynn Twin (9)

- Corpus Christi — United Artists’ Cine 4 (26)

- Dallas — ABC Interstate’s Inwood (27)

- El Paso — General Cinema Corporation’s Cielo Vista Mall Cinema I-II-III (19)

- Fort Worth — General Cinema Corporation’s Seminary South Cinema I & II (19)

- Galveston — General Cinema Corporation’s Galvez Plaza Cinema I-II-III (14)

- Houston — General Cinema Corporation’s Galleria Cinema I & II (36)

- Lubbock — Video Independent’s Cinema West (16)

- Port Arthur — Gulf States’ Park Plaza Twin (9)

- Richardson — ABC Interstate’s Promenade Twin (19)

- San Antonio — ABC Interstate’s Broadway (18)

- San Antonio — Santikos’ Century South 6 (22)

- Texarkana — Joy’s Cinema City Triplex

- Waco — ABC Interstate’s Cinema Twin (11)

- Wichita Falls — ABC Interstate’s Parker Square Twin (12)

UTAH

- Provo — Mann’s Academy (18)

- Riverdale — Tullis-Hansen’s Cinedome 70 Twin (16)

- Salt Lake City — Plitt’s Regency (27)

VERMONT

- South Burlington — CinemaNational’s Burlington Plaza Twin

VIRGINIA

- Hampton — Martin’s Riverdale Twin (19)

- Lynchburg — ABC Southeastern’s Boonsboro Twin

- Richmond — Neighborhood’s Westhampton (23)

- Roanoke — ABC Southeastern’s Towers Twin (15)

- Springfield — General Cinema Corporation’s Springfield Mall Cinema I & II (18)

- Vienna — Neighborhood’s Tysons (27)

- Virginia Beach — ABC Southeastern’s Pembroke Twin (20)

WASHINGTON

- Everett — General Cinema Corporation’s Everett Mall Cinema I-II-III (21)

- Kenmore — United’s Kenmore Drive-In (17)

- Lakewood — General Cinema Corporation’s Villa Plaza Cinema I & II (14)

- Seattle — Mann’s Coliseum (37)

- Tacoma — United’s Auto-View Drive-In (14)

WEST VIRGINIA

- Charleston — Capitol (17)

WISCONSIN

- Brookfield — General Cinema Corporation’s Brookfield Square Cinema I & II (20)

- Green Bay — Marcus’ Marc Twin (14)

- Kenosha — Carmichael’s Roosevelt (9)

- Madison — Marcus’ Esquire (17)

- Milwaukee — Marcus’ Skyway Triplex (27)

- Milwaukee — United Artists’ Northridge Triplex (27)

- Racine — General Cinema Corporation’s Cinema I & II (16)

WYOMING

No theaters in Wyoming played Jaws during Release Wave #1

YUKON

No theaters in Yukon played Jaws during Release Wave #1

PRODUCTION & EXHIBITION INFORMATION + TRIVIA:

Steven Spielberg told The New York Times in 2002: “Frankly, I don’t think that Jaws would do as well today as it did in 1975, because people would not wait so long to see the shark. Or they’d say there’s too much time between the first attack and the second attack. Which is too bad. We have an audience now that isn’t patient with us. They’ve been taught, by people like me, to be impatient with people like me.”

The longest theatrical engagement of Jaws in the United States was the 43-week engagement at the Alpine Twin in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The longest run in a single-screen theater was the 37-week run at the Coliseum in Seattle. The longest run with a move-over extension is believed to have been the 40-week engagement in Denver (27 weeks at the Cooper, followed by 13 additional weeks at the adjacent Cooper Cameo).

Jaws was test-screened on March 26th, 1975, in Dallas, Texas (at the Medallion), and on March 28th, 1975, in Lakewood, California (at Lakewood Center). An analysis of the screenings and questionnaire results prompted the filmmakers to shoot additional footage (in a Los Angeles swimming pool) for one scene. The final release version of the film was sneak-previewed in numerous cities during April and May of 1975 (often as a double feature with Universal’s The Great Waldo Pepper).

Jaws has been spoofed numerous times, most memorably in Mad (as Jaw’d), in Playboy (as Jugs), in the adult film Gums, on an episode of Saturday Night Live, and even in the Spielberg-directed 1941 and Spielberg-produced Back to the Future Part II.

Promotional slogans used for the Jaws release included “And so it began...” “She was the first...” “The terrifying motion picture from the terrifying No. 1 best seller.” “Amity Island had everything. Clear skies. Gentle surf. Warm water. People flocked there every summer. It was the perfect feeding ground.”

Author Peter Benchley appears as a reporter in the Fourth of July sequence.

Jaws was re-released multiple times between 1976 and 1979, adding tens of millions of dollars to its already phenomenal box-office take.

In September of 1975, Jaws overtook The Godfather to become the movie industry’s top-grossing movie. It held the Number One spot until November of 1977 when it was surpassed by Star Wars.

Jaws spawned three sequels, a theme park attraction, a video game, a musical, countless imitations, and several retrospective documentaries.

The first international, foreign-language presentations of Jaws were held in Portugal in October 1975, with most developed nations opening the movie in December. The difficult-to-translate title was re-titled for most international engagements. Foreign titles included Shark, The Killer Shark, The Summer of the White Shark, The Teeth of the Sea, and Jaws of Death.

For his Jaws music, John Williams won an Oscar, a Grammy and a Golden Globe.

The majority of Jaws was photographed on location in and near Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts.

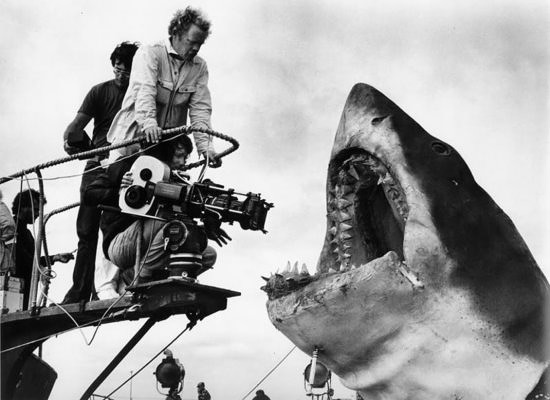

The original shooting schedule called for 55 filming days. The shoot was so problematic and difficult that, ultimately, principal photography lasted 159 days. Crew members jokingly referred to the film as Flaws.

Director Steven Spielberg was 27 years old when Jaws was produced. (Many references, including one elsewhere in this article, cite 26 as Spielberg’s age at the time. Spielberg was 26 when he was offered Jaws to direct, but the age discrepancy can also be explained by pointing out that biographical information published early in Spielberg’s career often cited his year of birth as 1947 when, in fact, he was born in 1946.)

In 1975 and 1976, Steven Spielberg participated in several Inside Jaws Symposium events held at educational institutions including Cal State Fullerton and the American Film Institute Center for Advanced Film Studies.

Jaws won three Academy Awards: Film Editing (Vera Fields), Original Score (John Williams) and Sound (Robert Hoyt, Roger Heman Jr., Earl Madery, John R. Carter). It addition, Jaws was nominated for Best Picture…. Aside from the Oscars, other awards and nominations Jaws received included an American Cinema Editors “Eddie” and Films and Filming Magazine’s Best Editing, a Grammy and Golden Globe for John Williams’ music, six BAFTA nominations, a Directors Guild and Golden Globe nomination for Spielberg’s direction, and a People’s Choice Award for Favorite Motion Picture. In addition, Show-A-Rama awarded Spielberg Director of the Year and the Publicists Guild awarded Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown Producers of the Year.

The shark featured in the film was a combination of special effects (mechanical sharks nicknamed “Bruce” by the crew) and real underwater footage of live sharks shot near Australia by Ron and Valerie Taylor (Blue Water, White Death).

The memorable “treadmill” shot (i.e. simultaneous dolly-zoom) of Brody reacting to the shark attack during one of the beach sequences is one of the most effective examples of such a shot. It was inspired by similar shots featured in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and has been used (often to great effect) in numerous films since.

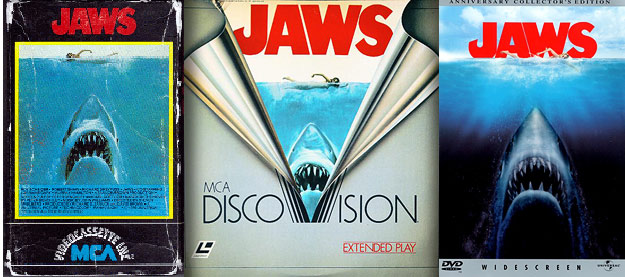

Ancillary markets…. In 1978, Jaws was the first movie mastered for release on the then-new DiscoVision videodisc format. The film was also among early releases on the Beta and VHS formats…. Jaws was first broadcast on Pay TV (i.e. cable television) in August of 1979…. Jaws was first broadcast on network television on November 4th, 1979. An estimated 80 million viewers tuned in to the ABC broadcast, and it was at the time the second-most-watched movie broadcast, being out-watched only by a 1976 airing of Gone With the Wind. Its first letterboxed home-video release, on LaserDisc, was in 1992.

Jaws is often mistakenly cited as the first motion picture to have grossed over $100 million. It was actually the first to exceed $100 million in rental revenue (i.e. the percentage of the gross receipts returned to the distributor). A few movies released prior to Jaws grossed over $100 million (but a rental figure less than $100 million), including The Sound of Music, The Godfather, The Exorcist, and, thanks to numerous re-releases, Gone With the Wind.

In February 1976, certain he would receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Director, Spielberg had a television news crew record his reaction to the announcement broadcast of the Academy Award nominations. To his shock and disappointment, and recorded for posterity, Spielberg was not nominated in the Best Director category. (Spielberg would subsequently be nominated seven times, winning twice.)

Jaws was the second collaboration between composer John Williams and director Steven Spielberg. Their first collaboration was The Sugarland Express in 1974. Subsequently, Williams has scored every one of Spielberg’s directorial efforts (except for his segment of 1983’s Twilight Zone: The Movie and 1985’s The Color Purple).

Repeat performances…. Jaws cast members Richard Dreyfuss, Murray Hamilton, Lorraine Gary, Susan Backlinie, and Ted Grossman appeared in subsequent Spielberg films. Hamilton, Gary and Backlinie all appeared in 1941 (1979), with Backlinie spoofing her role as the first shark victim. Dreyfuss played the lead in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and Always (1989). Ted Grossman appeared in small roles (and provided stunt work) in Spielberg’s Indiana Jones series and a few other films.

Jaws producers Richard D. Zanuck and Robert Brown also produced Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express (and offered Spielberg the Jaws directorial assignment during its production).

John Milius (The Wind and the Lion, Big Wednesday) and Howard Sackler (The Great White Hope) did uncredited rewrites of the script.

Roger Kastel was the artist who painted the famous image used on the cover of the Jaws novel and which subsequently was used on the film’s promotional material. (Other noteworthy work by Kastel included the “Style A” poster art for The Empire Strikes Back.)

The camera operator on Jaws was Michael Chapman, who would go on to a prolific career as a cinematographer (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Lost Boys) and director (All The Right Moves, The Clan of the Cave Bear).

In 1995, a feature-length retrospective documentary, produced by Laurent Bouzereau and showcasing new interviews with cast and crew members, was included on a collector’s edition LaserDisc set. A condensed version of the documentary subsequently appeared on the Jaws DVD. The original, full-length version appears on the Jaws Blu-ray Disc.

In 2001, Jaws was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

In June of 2005, Martha’s Vineyard hosted JawsFest, which featured a cast and crew reunion, Q&A and autograph sessions, film screenings and other activities.

THE INTERVIEW:

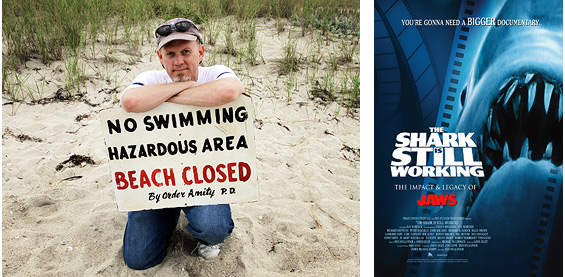

Steven Awalt is the author of Steven Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film Career (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014). A film historian and noted Spielberg authority, Awalt was the editor of SpielbergFilms.com from 2001 to 2009 and appeared as an interview subject in the 2007 Jaws documentary, The Shark is Still Working. He is currently working on a book on the making of The Sugarland Express.

Laurent Bouzereau is the writer, director and producer of The Making of Jaws, originally produced in 1995 for a Collector’s Edition LaserDisc release of Jaws and subsequently issued on the movie’s DVD and Blu-ray releases. In addition to Jaws, Laurent has made behind-the-scenes and retrospective documentaries for several Steven Spielberg films. Other documentary projects include Don’t Say No Until I Finish Talking: The Story of Richard D. Zanuck (2013), Roman Polanski: A Film Memoir (2011), A Night at the Movies: The Horrors of Stephen King (2011), and The Making of American Graffiti (1998). He has also written several books including Hitchcock: Piece by Piece (Abrams, 2010), The Art of Bond (Abrams, 2006), Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays (Ballantine, 1997), and The DePalma Cut: The Films of America’s Most Controversial Director (Dembner, 1988).

Sheldon Hall is the author (with Steve Neale) of Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010) and is a Senior Lecturer in film studies at Sheffield Hallam University, UK. He was a speaker at the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. Other books include Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It—The Making of the Epic Movie (Tomahawk Press, 2005; updated in 2014). He was editor (with John Belton and Steve Neale) of Widescreen Worldwide (Indiana University Press, 2010).

Erik Hollander is the director and co-producer of the 2007 documentary The Shark is Still Working: The Impact and Legacy of Jaws, which was included in the supplemental material of the Jaws Blu-ray Disc. He is an award-winning short-film director (The Doorpost Film Project, 2008), an on-set stills photographer, and has directed numerous documentaries and shot behind-the-scenes supplemental featurettes for motion pictures. He is an accomplished book cover and film poster artist and has served as book jacket designer for some of Steve Alten’s popular Meg novels and The Loch, as well as Titan Books’ edition of Matt Taylor’s Jaws: Memories from Martha’s Vineyard (2014). Presently, he is a freelance graphic designer at ErikHollanderDesign.com.

Joseph McBride is the author of Steven Spielberg: A Biography (Simon & Schuster, 1997; University Press of Mississippi, 2011, second edition; Faber & Faber, 2012, third edition; Chinese translation published in Beijing in 2012). A professor in the Cinema Department at San Francisco State University, McBride has written several other books, including Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J.D. Tippit (Hightower Press, 2013), Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (first published in 1992; 2000 revised edition, published by University Press of Mississippi, 2011), Searching for John Ford (first published in 2001; University Press of Mississippi, 2011), What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career (University Press of Kentucky, 2006), and Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless (Vintage, 2012). He was a co-writer of the screenplay for Rock ’n’ Roll High School (1979) and won a Writers Guild of America Award for the CBS-TV special The American Film Institute Salute to John Huston (1983).

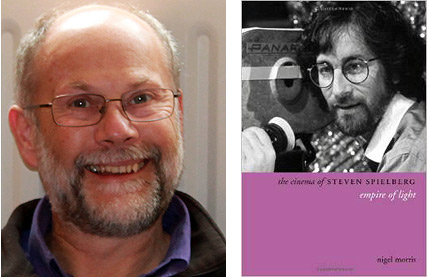

Nigel Morris was a keynote speaker at the Jaws 40th Anniversary Symposium at De Montfort University, Leicester, UK and is the author of The Cinema of Steven Spielberg: Empire of Light (Wallflower Press, 2007). He is the Principal Lecturer in Media Theory, School of Film & Media, University of Lincoln, UK. Nigel convened the first international conference on the work of Steven Spielberg (Spielberg at Sixty) at the University of Lincoln in 2007. He guest edited a Spielberg special edition of The New Review of Film and Television Studies in 2009 and is Project Editor of The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Steven Spielberg (forthcoming, 2015/16).

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

---

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is Jaws worthy of celebration on its 40th anniversary?

Steven Awalt: Jaws is more than worthy of celebration on its 40th anniversary or at any given time when people want to talk about great movies. The fact that we’re still talking about Jaws, passionately even, speaks to the film’s importance in cinema history and popular culture. While the film’s fashions or even the grain of the stock it was shot on may grow more foreign to new audiences and younger generations, I can’t foresee the heart of the film—the characters and its impeccable sense of exciting, high-emotion storytelling—ever falling out of fashion.

Laurent Bouzereau: Jaws was defining for a whole generation of filmgoers, but it’s one of those special films that is still relevant today. You look at the film and it still “works.” The approach to the story and the characters still feel fresh, and Steven Spielberg’s vision is timeless. It’s worthy of a 40th Anniversary celebration—and I predict it will be as worthy in another 40 years!

Sheldon Hall: It’s undoubtedly a landmark in contemporary American cinema, and not just because of its commercial success and influence. It also happens to be a very good movie!

Erik Hollander: I think the better word is “ways”—plural. Having spent seven years of my adult life exploring this very thesis with our doc, The Shark is Still Working, I can tell you there are enough “ways” to necessitate the drastic cutting of material from it—simply for time’s sake. I’ve lost count of how many documentaries, retrospectives, books, articles, blogs, tributes, pop culture references, and spoofs have been made on this one single film. Whether celebrating the movie itself, or recollections of its infamously troubled production, public fascination with Jaws never seems to dry up. I’m hard pressed to think of another single motion picture, made in the last forty years, that has been as documented and studied as this one has. (Maybe the original Star Wars?)

Joseph McBride: It helps remind us that good filmmaking, good drama of any kind—even in a “blockbuster”—relies primarily on character. Jaws is a fine character piece about three disparate men on a boat who air their differences in the midst of action and find some similarities and rally together to conquer an external menace. The suspense comes as much from their interactions with each other, and with the shark, as it does from the mechanics of the shark itself. The fact that the shark rarely “worked” helped Steven Spielberg and his colleagues concentrate on the characters while mostly suggesting the external menace. There’s a lesson here for those who make movies composed of little more than giant pieces of indistinguishable metal smashing into each other for two hours and forty minutes. Spielberg, among his many other roles, unfortunately has become Michael Bay’s enabler on the Transformers movies, which represent the worst in today’s degraded filmmaking environment, but that is part of the price Spielberg pays for preserving his relative independence and being able to make his own more personal films such as Lincoln or A. I. Artificial Intelligence or Amistad.

Nigel Morris: Same reasons you’d celebrate anything. It’s good—really good. But beyond that it’s a commemoration. Jaws is seen, rightly or wrongly, as the movie that changed cinema history. It was the first to break the $100 million box-office barrier. That led a lot of snooty critics to accuse it of dumbing down, crass commercialism, appealing to lowest-common-denominator base instincts, and so on. The fact that, four decades on, it’s still held in huge affection—we wouldn’t be having this conversation if it weren’t—proves that there was much more to it than clever marketing.

Coate: When did you first see Jaws and what was your reaction?

Awalt: I actually have no concrete visual recollection of the first time I saw Jaws, which kind of pains me as an admirer of Steven’s work. In its way, it feels like a pre-natal experience for me, like something that was always there, formed in the same evolutionary soup all of our generation once swam in. I’m fairly certain I first saw it when it was broadcast on network television in the late 1970s, at least that’s my vague memory about it. I do have a funny story about Jaws when I was young, though. I was a massive fan of Close Encounters of the Third Kind at a very young age, but the very concept of Jaws petrified me. We were at the grocery, I’m assuming around ’76, ’77, and one of those old gum-ball machines had big plastic pods in which folded mini-posters were tucked inside. There was a Jaws poster you could get, amongst other popular movie and TV show images. I really wanted to get the poster of John Travolta from Welcome Back, Kotter. Of course I wound up with the poster with the image of the gore-slicked shark (a publicity shot used for the film’s marketing, but not from the film) instead of Vinnie Barbarino, and I wanted nothing to do with the Jaws poster. My older sister and brother cruelly (but damned funny in hindsight) taped the Jaws poster above my bed so when I rolled over on my back and looked up, instant terror. Thankfully, by the time we saw the film’s network TV premiere, I’d found enough courage to watch, surely hiding behind my hands or the couch at times, but I learned to love the shark despite my fear of it. That love increased exponentially as I grew up and grew into the film’s many, many charms.

Bouzereau: I saw Jaws as a reissue release. In France, where I grew-up, the film was restricted to anyone under 13 and I didn’t make the cut that year. The interesting thing is that I collected all of the lobby cards, the poster, I knew the soundtrack by heart and I had read the book by the time I saw it. It was a fascinating experience to finally see the film after fantasizing about what it was like through photos, a novel and a score! Needless to say, it didn’t disappoint!

Hall: I saw Jaws for the first time at the ABC Haymarket Cinema in Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, in early 1976—my hunch is that it was in February. I now know that its run of 13 weeks was the longest in that cinema’s history (the building is no longer extant). I have quite a vivid memory of that evening, when I was eleven years old. I went with my parents (it was relatively rare for both to go with me—one or other usually had the duty). There had been a lot of anticipation about it and we all loved the movie. I recall the audience reaction to the big shock moments and climax, but also my parents’ response to the warmth of the Brody family scenes. I still have the souvenir brochure that was bought for me on that evening.

Hollander: Jaws came out when I was eight, and my well-meaning parents deemed me too young to go see it. This, of course, only served to make me want it all the more. The airwaves were flooded with Jaws TV spots which were mesmerizing to me. Percy Rodrigues’s menacing voice over a silhouetted nude woman’s form followed by a violent tug on her leg sent chills down my spine every time. Those images, combined with the Bantam novel’s terrifying cover of a giant shark with a mouth full of knives were enough to hook me—big time. Soon, it seemed I was the only fourth-grader who hadn’t seen what had become all the buzz on the playground. Admitting to your grade school peers that you were “not allowed” to see the coolest movie ever was not an option, so I did what any kid in my shoes would do: I lied. After gleaning sufficient details from all the chatter around me, I began parroting my “favorite parts,” making sure to “recount” the shark scenes in broad brush strokes so as not to betray a false detail I wouldn’t be aware of…. Three years of dwelling on these second-hand memories weaved together for me an alternative interpretation of the movie—one I can still remember. In 1978, when the movie was re-released for a limited engagement, I was finally taken by my dad to see it. Never had I experienced such anticipation. I still remember shaking like a leaf for the first 30 minutes—partly for the excitement, partly for the terror, and partly because it was freezing in that theater. Surprisingly, for all the time my fertile imagination had to do its work over the years, the real thing surpassed my wildest expectations. It instantly became my favorite movie. And my obsession. When Jaws made its network TV debut a year later on ABC, it was an event. I taped it on audio cassette, pausing to edit commercials out, and spent many years repeatedly listening to it, searing every word— every sound—into my memory forever.

McBride: I first saw it at the initial Hollywood preview at the Cinerama Dome on April 24th, 1975. That was the third time it had been shown in public (following previews in Dallas and Long Beach, California). I knew Jaws would be a huge hit at the moment when the young woman swimmer is yanked under by the shark, and the whole audience jumped in a rolling movement. I had never seen that happen before. I enjoyed the film but have to admit that I underrated it for a while because at the time I thought, as did some others, that while it was undoubtedly an efficient thriller, it also seemed something of a regrettable advance in Hollywood’s march into Grand Guignol territory. I was wrong. Now it seems notably tame and character-driven. Jaws was something of an accidental blockbuster. It should not be blamed for being a good movie. Carl Gottlieb’s witty shooting script (adapted with Peter Benchley from the latter’s pulpy novel) has a lot to do with its quality, along with the acting of Richard Dreyfuss, Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, and Lorraine Gary (who never gets enough credit for her relaxed, believable, and often droll portrayal of Scheider’s wife). Spielberg’s least-discussed talent is that he is a superb director of actors. As actor-director Anson Williams, who acted for Spielberg on TV in his youth, told me: “Any director can get a great performance out of Al Pacino, but how many directors can get a great performance out of a rubber puppet (in E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial)?”

Morris: Well, that’s an interesting one! David Brown, one of its producers, claimed that everyone remembered their first viewing of Jaws. Believe it or not, I was 20 when the movie came out but it took me something like another 10 or 15 years before I saw it. I’d been aware of all the hype—it was impossible to ignore, over here in the UK just the same as Stateside—and I made a decision that I was not going to be manipulated by commercial interests into joining the herd, as I saw it. I’d just finished my first year at university, studying English. The way I was taught was that the sign of whether anything was worthwhile was if it stood the test of time. Outside the curriculum I was seeing all the recent American New Wave movies and catching up on the older classical Hollywood and European and World Cinema stuff that I’d missed thanks to my small-town suburban upbringing. There was no DVD or downloading in those days and the only way to get a crash course in film was to join film societies or go to art houses. I did both, three or four times a week, because being in a student community made it possible. Even in the days before Jaws and Star Wars, anything that was mainstream Hollywood was tainted with commercialism and had to prove itself (as exceptions such as The Godfather and The Exorcist had done). Much of what was aimed at the masses seemed pretty clapped out and cynical, formulaic, and populated by geriatric actors: think of Earthquake, The Towering Inferno, Airport, and The Poseidon Adventure. The louder Hollywood shouted the more desperate it seemed to be…. A year later I was over in the States as an exchange student. The films that excited the kids there were different, but the ones on the billboards and the cover of Time and Newsweek were just the same. I shuddered and carried on watching character-driven dramas, heavy with symbolism, and often subtitled. Nothing wrong with that, I hasten to add, but I was inadvertently depriving myself of a balanced diet. I really enjoyed Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. when they came along but didn’t immediately twig the connection with Jaws. It was only when I started teaching film at high school level in the 1980s that I realized, because it was a non-assessed, elective course that I’d have to get to grips with what the students were watching. At the same time I did a stint as a radio film critic for a couple of years and had to pass judgment on a lot of Hollywood movies. Suddenly the penny dropped—most Hollywood movies were dross but a few were brilliant; but that was true also of other media, literature, even art movies, the worst of which had been filtered out before they got anywhere near me. It must have been around then that I first watched Jaws—probably on a rented VHS cassette—and, even on a small square screen, I was blown away by it…. If you’d told me when I first heard of Jaws that I’d be giving a keynote at the 40th anniversary symposium or doing a transatlantic Q&A for the Internet, I absolutely would not have believed you. To be honest, if you’d told me then that I’d be making my living teaching film, and certainly if you’d described the Internet to me, I wouldn’t have believed you either. And that perhaps is the point. Jaws is a relic from another era. But it seems as fresh now and it works just as well as ever.

Morris: Well, that’s an interesting one! David Brown, one of its producers, claimed that everyone remembered their first viewing of Jaws. Believe it or not, I was 20 when the movie came out but it took me something like another 10 or 15 years before I saw it. I’d been aware of all the hype—it was impossible to ignore, over here in the UK just the same as Stateside—and I made a decision that I was not going to be manipulated by commercial interests into joining the herd, as I saw it. I’d just finished my first year at university, studying English. The way I was taught was that the sign of whether anything was worthwhile was if it stood the test of time. Outside the curriculum I was seeing all the recent American New Wave movies and catching up on the older classical Hollywood and European and World Cinema stuff that I’d missed thanks to my small-town suburban upbringing. There was no DVD or downloading in those days and the only way to get a crash course in film was to join film societies or go to art houses. I did both, three or four times a week, because being in a student community made it possible. Even in the days before Jaws and Star Wars, anything that was mainstream Hollywood was tainted with commercialism and had to prove itself (as exceptions such as The Godfather and The Exorcist had done). Much of what was aimed at the masses seemed pretty clapped out and cynical, formulaic, and populated by geriatric actors: think of Earthquake, The Towering Inferno, Airport, and The Poseidon Adventure. The louder Hollywood shouted the more desperate it seemed to be…. A year later I was over in the States as an exchange student. The films that excited the kids there were different, but the ones on the billboards and the cover of Time and Newsweek were just the same. I shuddered and carried on watching character-driven dramas, heavy with symbolism, and often subtitled. Nothing wrong with that, I hasten to add, but I was inadvertently depriving myself of a balanced diet. I really enjoyed Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. when they came along but didn’t immediately twig the connection with Jaws. It was only when I started teaching film at high school level in the 1980s that I realized, because it was a non-assessed, elective course that I’d have to get to grips with what the students were watching. At the same time I did a stint as a radio film critic for a couple of years and had to pass judgment on a lot of Hollywood movies. Suddenly the penny dropped—most Hollywood movies were dross but a few were brilliant; but that was true also of other media, literature, even art movies, the worst of which had been filtered out before they got anywhere near me. It must have been around then that I first watched Jaws—probably on a rented VHS cassette—and, even on a small square screen, I was blown away by it…. If you’d told me when I first heard of Jaws that I’d be giving a keynote at the 40th anniversary symposium or doing a transatlantic Q&A for the Internet, I absolutely would not have believed you. To be honest, if you’d told me then that I’d be making my living teaching film, and certainly if you’d described the Internet to me, I wouldn’t have believed you either. And that perhaps is the point. Jaws is a relic from another era. But it seems as fresh now and it works just as well as ever.

Coate: How is Jaws significant within the thriller genre?

Awalt: The best thing about Jaws as far as genre designation goes is that while large passages of it fit into the thriller genre, and stand as top-shelf examples of how great scenes of cinematic tension are planned, designed, engineered and constructed (not a bad thing, as film is emotional, artistic and mechanical), it’s not entirely accurate to designate the film as simply "a thriller." That makes it hard for me to rank it within the genre. Along with its thrills, Jaws is terrifying, grotesque (horror genre), filled with compelling, engaging, feeling and funny characters (drama, comedy genres), exciting as hell, especially in the third act (adventure genre), and all of the elements that we ascribe to films to give them generic designations rise and fall, entwine, push to the forefront or move off stage depending on the act, the sequence, the scene or even given moments in a scene. So the moments of expertly-crafted thrills in Jaws would rank it as an example of a film absolutely worthy of study for those filmmakers intending on making thrillers, but Jaws stands above any single genre. It’s one of cinema history’s best horror-thriller-drama-comedy-adventure films.

Bouzereau: It always threw me to see Jaws called a thriller. Marathon Man was also called a thriller and there’re two very different types of films. To me, Jaws is a monster movie, an adventure film and yes, thrilling.

Hall: I’m not sure that I’d describe it as a thriller, though it has plenty of thrills. The first act more closely resembles a horror film, the second act is a melodrama of sorts (small-town politicking and all), and the last act a sea adventure. This generic mix is in itself interesting and significant.

Hollander: Jaws seems to be one of the few thrillers that transcends the genre. Its pitch-perfect balance of horror, suspense, drama, humor and adventure place it far above any of its contemporaries—especially its imitators. I think it bridged the gap between the horror and adventure genres, all while elevating them to a higher cinematic treatment than formerly seen. The result was a new kind of thriller and a new collective appetite for them.

McBride: It’s akin to the Val Lewton films of the 1940s in which the menace was more suggested than seen. Lewton knew that fear was more effectively conveyed in the mind than by mayhem on the screen. Spielberg is a film maven who probably knows the Lewton films well, but his initial conception for Jaws was more blatant, with the shark jumping out of the water more often and doing more violent tricks. He admits that the hokiest part of the movie is when the shark jumps onto the boat and eats Robert Shaw. It had to happen, but the shark creator, Bob Mattey, had scrimped on the cost of the motor, so the shark looked anemic as it jumped. Zanuck/Brown production executive Bill Gilmore told me in an interview for Steven Spielberg: A Biography, “The shark sort of came up like a limp dick, skidded along the water, and fell onto the boat.” Spielberg threw a fit but was forced by Gilmore to move on and use his and Verna Fields’s editing magic to cut around it. And by necessity, since the shark seldom worked, Spielberg mostly used the barrels and the unseen presence of the shark to cause fear. It’s mostly psychological. And John Williams’s music, which Spielberg admits is fifty percent of the effect of the movie. When you look at Jaws rushes with the mechanical shark tooling through the water with grinding valve noises, it’s comical. Jaws easily could have been ridiculous, but it’s a masterwork of suspense thanks largely to the shark not working and Spielberg and his team creatively working around that problem.

Morris: There’s some debate, actually, about what genre it belongs to. In its early days it was widely regarded as science fiction, probably because of the way it presented a largely off-screen alien threat to a human community. Then again, it’s a horror flick with its monster dismembering human bodies before our very eyes, even if we don’t directly see it. Also it’s a buddy movie, in the way it builds the relationship between Brody and Hooper as they deal with both Quint and the shark…. But Hollywood studios don’t really deal in genres. They are an after-the-event categorization imposed by critics, academics, fans, and subsequent markets such as broadcasters and, back in the good old days, video rental stores. There are two exceptions. The first is the B-movies that Jaws in many ways resembles. They were given genre descriptions so that theater managers would know how best to program them alongside the main features. But often their categories shifted. The Universal horror movies of the 30s, for example, were marketed as science fiction when they were re-released in the 50s, not least because sci-fi had become the more popular genre. The other exception is the low-budget straight-to-video movies that cash in on the success of a hit; they had to be designated a genre so the video shops would know where to shelve them. Jaws succeeds in being what every other mainstream new movie claims to be—not like something you’ve seen before but, as the grizzly voiceovers in the trailers say, an unprecedented motion picture experience.

Coate: Where do you think Jaws ranks among Steven Spielberg’s body of work?

Awalt: As far as mainstream, critical and even academic consideration for Jaws over the decades, the film surely sits at the top-tier of Spielberg’s work. For audiences, it seems to maintain the same vintage as Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., Jurassic Park, and on the opposite end of the spectrum, Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan…. For critics and entertainment journalists, it retains its juice as a film to write about even after four decades, although in more recent times there’s a paucity of thought or originality, with most trotting out the inaccuracies of how the film supposedly created from whole-cloth the summer market for films (patently untrue), the “blockbuster” (hugely untrue and exposing a willful ignorance of cinema history), how it sounded the opening chimes of the death knell for serious cinema (films both great and poor, original and imitative, transcendent and sheer dreck have been peddled by producers, studios and indies long before Jaws, to this day, and surely will be well into the future). "Hollywood" is still in business, and arguably remained viable thanks to the wave that films of the mid-to-late 1970s like Jaws and others created…. As far as Steven’s personality in his films, his lightness of touch with and humanist insight into his characters are there and his woefully underrated handling of both character comedy and situational comedy is razor sharp. And while Jaws is easily one of Spielberg’s best jobs out as far as his direction is concerned (it’s like a precision clockwork how it’s built) it doesn’t shine as brightly in a personal sense. That’s absolutely not a criticism of Jaws, but just to note that we’d have to wait until real personal passion projects like Close Encounters and E.T., along with Poltergeist (a film riddled with Spielberg’s fingerprints and even DNA no matter what the credits read) to see a clearer window into the man and also the boy inside the man. Steven has said Jaws was a mechanical film for him, but I do think he undersells his essential spirit within the film. So if he had yet to put all of his soul into a film, Jaws certainly has Spielberg’s truly unique imagination and heart. Just imagine how different it would be if any other director shooting in 1974 had made it…. As for my own tastes, I adore Jaws to my marrow. It’s as near perfect as a film could be, and I have yet to tire of seeing it at home and especially projected on the big screen (the best way to see the film).

Bouzereau: It is my favorite Steven Spielberg film and one that continues to inspire me. It is perfection on all levels of storytelling, acting and filmmaking.

Hall: It’s still among his finest work, and it remains my personal favorite of his films.

Hollander: Since Jaws irrevocably remains my favorite film, it’s hard to answer that objectively. I’d say that while it may not necessarily be the best-crafted or most culturally significant of his films, I do think an argument could be made for it having the most diverse set of high-water marks within his body of work. But that’s for a different question. One thing is certain, Jaws is the movie that launched his career out of gravitational pull and into the stratosphere where he would remain to direct so many diverse and wonderful films. Speaking to this, when interviewing Mr. Spielberg for The Shark is Still Working, we asked him, “Viewing all your films as your ’children,’ which child would Jaws be?” He replied, “Jaws would have to be the errant, wayward child who never listened to his father, but wound up growing up, doing good, and then supporting his father for the rest of his life.” Ever the storyteller…. As for my personal picks, the top five Spielberg films, based on their original emotional impact on me, are as follows: (1) Jaws (childhood obsession/fear), (2) Raiders of the Lost Ark (edge of seat excitement), (3) Schindler’s List (sobering, disturbing, important), (4) Saving Private Ryan (reverence, gratitude), (5) E.T. (wonder, and yes, I cry a little at the end).

Hollander: Since Jaws irrevocably remains my favorite film, it’s hard to answer that objectively. I’d say that while it may not necessarily be the best-crafted or most culturally significant of his films, I do think an argument could be made for it having the most diverse set of high-water marks within his body of work. But that’s for a different question. One thing is certain, Jaws is the movie that launched his career out of gravitational pull and into the stratosphere where he would remain to direct so many diverse and wonderful films. Speaking to this, when interviewing Mr. Spielberg for The Shark is Still Working, we asked him, “Viewing all your films as your ’children,’ which child would Jaws be?” He replied, “Jaws would have to be the errant, wayward child who never listened to his father, but wound up growing up, doing good, and then supporting his father for the rest of his life.” Ever the storyteller…. As for my personal picks, the top five Spielberg films, based on their original emotional impact on me, are as follows: (1) Jaws (childhood obsession/fear), (2) Raiders of the Lost Ark (edge of seat excitement), (3) Schindler’s List (sobering, disturbing, important), (4) Saving Private Ryan (reverence, gratitude), (5) E.T. (wonder, and yes, I cry a little at the end).