CHAPTER 5: THE CINEMATOGRAPHY

M. David Mullen, ASC (cinematographer, The Love Witch, The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel; co-editor, American Cinematographer Manual Eleventh Edition): The 1983 Oscar Cinematography nominations pointed to the new era of film stocks—you had one feature shot on Fuji high-speed stock get nominated, Das Boot, and two others used the first high-speed Kodak stock to come out, 5293, but E.T. and Gandhi were shot on slower Kodak 5247, the 125 ASA film stock released in the mid-1970s. They were probably in production before the new Kodak stock became available in 1982.

Allen Daviau’s use of smoke and shadowy lighting transformed the mundane suburban setting into something magical, more like life as seen through the eyes of a child. To help with this perspective, the movie is often shot from lower angles with wider-angle lenses. Spielberg and Daviau also studied Alien (photographed by Derek Vanlint), calling it a textbook on textured lighting. Besides haze, much of the movie was shot with a light Double Fog filter, creating halation around light sources (McCabe and Mrs. Miller, photographed by Vilmos Zsigmond, is one of the more notable examples of the use of a Double Fog for diffusion.) In E.T. there is also a complex version of the dolly-zoom combination made famous by Hitchcock in Vertigo (and used by Spielberg in The Sugarland Express and Jaws for a key moment.) The shot involves a hilltop view of the neighborhood where the government agents looking for E.T. are revealed, ending on a shot of keys hanging from actor Peter Coyote’s belt.

Allen Daviau was not a fan of anamorphic lenses, perhaps because he preferred a less-wide aspect ratio that was closer to the frame used by the European art films and classic Hollywood films that he admired. Also, for various reasons, the 1980s was a period of decline for anamorphic photography until a resurgence in the 1990s. Some say it was because of the rise of home video before letterboxing had become accepted, causing filmmakers to avoid the experience of seeing their 2.40:1 anamorphic framing butchered by panning-and-scanning. But in the case of E.T., the use of 1.85:1 instead of 2.40:1 might have been a signal to the audience that Spielberg was making a more intimate, personal film rather than a spectacle.

CHAPTER 6: THE MUSIC

Mike Matessino: By the time Steven Spielberg made E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, it was not at all surprising that John Williams would compose its score. It was their sixth project together, three of which—Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Raiders of the Lost Ark—had yielded instantly recognizable music. The latter of these was a collaboration between Spielberg and Star Wars creator George Lucas, which solidified the sheer creative power and box office dominance that both men had brought to cinema. John Williams was the musical voice not only of the films the pair made, but of the era itself.

Raiders was an important milestone for Spielberg. As successful as Jaws and Close Encounters had been, both had gone over-schedule and over-budget. When the same thing happened with the epic comedy 1941, only with no blockbuster receipts saving the day at the back end, Spielberg’s sure-fire bankability was questioned. It even gave Lucas pause about having him direct Raiders, which his company was itself financing. But Spielberg promised to finish the first Indiana Jones adventure on-time and on-budget, which he not only fulfilled but exceeded. Apart from assuring its financial success, Spielberg came away from the experience with a discipline of working efficiently that stays with him today.

Following his first two hits, Spielberg had begun backing other films as an executive producer, but with the success of Raiders came the ability to formally establish “Amblin Productions” through the auspices of M-G-M, which had agreed to make the Spielberg production of Poltergeist. E.T. was made in parallel, to be released by Universal, although it was filmed at the neighboring Laird Studios (previously Desilu Culver and the Selznick International). The film went before the cameras in September 1981, after Poltergeist had wrapped, and even during filming Spielberg discussed what he had in mind for Williams’ music: “It’s to be a very expansive score, and yet it’s going to focus down in a rather intimate style because it’s a love story. We need pure violins and oboes, and harp and piano, and a rather quiet ensemble probably comprised of over 70 musicians. This movie is a tiny epic and I think John’s score will be very suitable for that description.”

Williams had recorded his scores for Jaws, Close Encounters and 1941 at the 20th Century Fox and Warner Bros. scoring stages, with Raiders taking place in London, where the production (like the Star Wars films) was based. But with Amblin’s deal at M-G-M came access to their legendary stage, and on the day after Williams’ 50th birthday, February 9, 1982, the composer came to the final Jerry Goldsmith session for Poltergeist and was asked by Spielberg if he could do E.T. there with the same core crew. This would include music editor Ken Hall, who, along with Williams, had been among the talent present in Lionel Newman’s music department at Fox in the 60s, and recording engineer Lyle Burbridge, whose career had started by recording Williams’ underscore cues for the 1969 musical version of Goodbye, Mr. Chips. As for the M-G-M stage, it was a homecoming, as Williams had played there as a session pianist in the late 50s and into the 60s. Herbert Spencer, another alum from the 20th days, would orchestrate E.T. (and he’d even done a couple of cues on Poltergeist), and supervising the cutting-edge digital mix-downs would be Bruce Botnick, who would become Goldsmith’s regular scoring mixer beginning the following year.

E.T. scoring began on March 25, 1982, and among the first music recorded was for the finale of the picture, specifically The Bike Chase and The Departure, which yielded the most oft-recounted anecdote from the sessions. Williams had designed both cues to precisely synchronize with specific visual and emotional beats on the screen, but the fluid tempo variances proved difficult to achieve. Spielberg then offered the solution: he would let Williams record the music without the picture, capturing the tempos that felt emotionally right, and then later recut the film to the music. Williams summarized the result: “I think part of the reason the end of the film has such an operatic sense of completion and real emotional satisfaction, is that it was music first, and then refinement of the picture editing second.”

The Bike Chase was one of the few action-based cues in the E.T. score. In contrast to what Spielberg’s previous films has required of the composer, the music reflected the director’s note that it was, essentially, a love story, and called for a purity of instrumentation. Rich with thematic material, its melodies all related to each other (as well as subtly, almost subconsciously, connecting with some of Close Encounters’ music), E.T. features several noteworthy solos for flute, piano, and harp. The ensemble called for two of the latter instrument, played by Dorothy Remsen and Catherine Gotthoffer, who offer a duet of the theme in the cue At Home. It is in the score’s more intimate passages such as this, rather than the action material, that the Spielberg-Williams collaboration truly solidifies in the score for E.T. In this masterwork (arguably among many for both men), Williams finds the emotional core of the story, characters, and the suburban and forest settings, and helps it resonate on levels beyond the tangible.

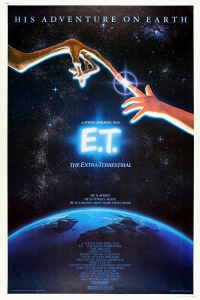

Recording sessions for the film concluded on April 2, 1982, but an additional two days at the end of the month were booked for album arrangements, which comprised about half the running time of the soundtrack that was released the same week as the film. As a listening experience it worked beautifully, freed of narrative constraint and conveying the thematic material almost as an emotional memory. The album achieved Gold Records status and won two Grammy Awards, both for best soundtrack as well as for the track Flying, which presents the well-known main theme and instantly summons the iconic image of harvest moon-silhouetted Elliott and E.T. on airborne bicycle. Said icon would, in just two years’ time, become the logo for Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment, formed with E.T.’s and Poltergeist’s producers (and soon to be spouses) Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall, established at Universal Studios, where it remains today.

The music of E.T. has had a remarkable life beyond the movie. Williams began his third season as principal conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra just as the film was completed, and immediately added selections from the score to concert repertoire. The following year the composer received an Academy Award for the score (his fourth), followed by the aforementioned Grammys. He then revisited the material in 1990 for the theme park ride The E.T. Adventure, and in 1996 the first expanded version of the score was released. An updated version appeared in 2002, when the film was reissued for its 20th anniversary (in a since retracted, recut and CG-tweaked edition), the celebration kicking off with Williams conducting live orchestra in sync to the picture. This event in itself laid the groundwork for the numerous live-to-picture concerts that we enjoy today, with E.T. itself being presented beginning in 2016, including a newly composed “entr’acte” penned by Williams to begin the second half of the program. Another updated and remastered presentation of the soundtrack, that I produced with original mixing engineer and album producer Bruce Botnick, was released for the film’s 35th anniversary in 2017. For the first time, the full film score, along with alternates and extras, plus the 1982 original soundtrack album, were all comprehensively presented in a single package. The 40th anniversary was marked with an IMAX format reissue of the film, coming in the midst of celebration for Williams’ 90th birthday and just ahead of the 50th anniversary of the remarkable director-composer collaboration. Clearly there is every reason to be “over the moon” about John Williams’ timeless music for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

CHAPTER 7: THE SOUND

Bill Mead (Dolby Laboratories): By 1982, Dolby had become a critical ingredient brand that simply meant that a particular cinema had invested in equipment that would deliver the best sound. Prior to the 1977 Star Wars release, many moviegoers in the smaller markets had never heard surround sound before. The standard 35mm soundtrack was plagued with clicks and pops, distortion, and was generally a bad audio experience. The audiences may not have understood the technology, but they had become aware of Dolby from their experiences with the Dolby releases beginning with Star Wars, and on to many other blockbuster titles. They knew that a Dolby-equipped theatre, identified by the Dolby logo, would give them a sound experience that was better than what they would get otherwise. Those moviegoers in the major markets where a 70mm Dolby print was available, got a state-of-the-art sound experience. This is still true today, with Dolby Cinema and Dolby Atmos.

Steve Lee (The Hollywood Sound Museum): Creating believable sounds for alien creatures in movies can be pretty tricky, especially when the character is a completely manufactured puppet. But the sounds of E.T. are absolutely brilliant and completely sell that character to the audience. The sound effects for the film were supervised by the late great Charles Campbell, and E.T.’s voice was by Star Wars sound designer Ben Burtt. He mostly used the voice of an old chain-smoking woman named Pat Welsh that he met in a Northern California camera shop. She had a peculiar, androgynous voice... you couldn’t tell if it was male, female, or an alien creature! Ben supplemented it with otters and other animals he recorded. (He hired Pat again later for the voice of bounty hunter Boushh who is Princess Leia’s disguise in the first part of Return of the Jedi.). I remember hearing that they were very concerned that E.T. might be too scary for small kids. So Steven Spielberg gave a note to the Foley crew performing movement sound effects for the film that they should do whatever they can to "make E.T. funnier." When E.T. is getting drunk in the kitchen and waddling around, they filled a T-shirt with Jell-O for some funny sloshy body movement sounds. Really clever stuff. Chuck Campbell and Ben Burtt won the Oscar for Best Sound Editing that year for the film. [And for the film’s production audio and re-recording mixing, Robert Knudson, Robert Glass, Don Digirolamo and Gene Cantamessa won the Oscar for Best Sound.]

CHAPTER 8: THE SPECIAL EFFECTS

Joe Fordham (writer, Cinefex): I considered myself a savvy movie-goer, Harryhausen aficionado, early consumer of imported Cinefex magazines, and a dabbler in Super-8, so I was cocky in my knowledge of go-motion and animatronic creations. But this thing confounded me. E.T. was a perfect illusion, and completely spellbinding.

William Kallay: Carlo Rambaldi’s creation of a moving and three-dimensional being still astounds me. The combination of puppetry and the voicing of E.T. made him all the more believable.

John Scoleri (co-author, The Art of Ralph McQuarrie): Ralph’s primary role was designing E.T.’s ship. This time out, Ralph’s marching orders were to create a ship that looked like Dr. Seuss designed it. Ralph said, “I thought that was kind of interesting. Very off the wall. I made five or six sketches of spaceships… Steven looked at them. I think I sent them down to L.A., he looked at them there, and he picked one out and I made a painting of it. They built the model at ILM, it looked almost exactly like the painting. And it had all the features, with the retractable lights and everything. It was amazing. They did a beautiful job and I thought it was good. I suggested that it take off with a sort of a blue flame, which they did, and as it lifted into the evening sky it would be very quiet, and the sound of like a jet in the distance, like an airliner, would come in as it disappeared. They did all that I think pretty much the way I described it in my sketch.” Ralph was also asked to come up with some alternate concepts for E.T. himself; including embellishments on the design based on reference photos of Carlo Rambaldi sculpts: “Steven was working with Carlo Rambaldi, and he had sculpted what was really E.T. Steven was just kind of tweaking little wrinkles and so forth, and he had me making sketches of E.T.s, and I made a whole lot of off-the-wall E.T.s. Rambaldi’s version stood up. Steven was just wanting to get another opinion, you might say, which I gave him. But he stayed with the E.T. that Rambaldi made, which I thought was very good.”

Julie A. Turnock (author, The Empire of Effects: Industrial Light & Magic and the Rendering of Realism): The film is a good example of ILM’s maturing house style. ILM only opened to outside (non-Star Wars) business in 1980, so E.T. is a good example of the ILM artists applying what they learned on the original Star Wars and showing their range; in this case, for more “real life” earthbound effects.

Joe Fordham: Steven Spielberg memorably stated it was John Williams that made the bikes fly in E.T. Without a doubt, the musical score was the transformative magic that put the breath of life into those two sequences in E.T. In my first screening, during the classic shot of E.T. and Elliott silhouetted against the moon audience members cheered and one person popped a flashbulb photo of the screen in the darkened theatre of the Empire Leicester Square. What’s heart-stopping about that scene is the authenticity of the image for such an iconic fantasy emblem. E.T., Elliott, and the moon have become as emblematic of cinematic magic as Georges Méliès’ moon face with a rocket in his eye. As Cinefex revealed in Paul M. Sammon’s January 1983 article, it was Industrial Light & Magic effects cameraman Mike McAlister, working under visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren, who captured that moon as an original motion picture image. After calculating the moon’s ascension, and the exposure and composition of a 1000mm lens, it took three months of long cold nights in a Marin County valley to capture that giant silvery, shimmering orb perfectly through the trees. Little Elliott and E.T. were go-motion miniatures brought to life with subtle motion control movements under animation supervisor Sam Comstock. The 20th anniversary version gave Elliott a flapping cape. But it was still pure magic. And it was the same attention to detail that brought the boys’ final flight to life. Spielberg and cinematographer Allen Daviau’s choice to have the boys race through dappled lighting of an end-of-the-summer’s-day in Granada Hills gave a perfect strobing light effect, emphasizing E.T.’s magic. ILM replicated the light and shadow play in their bluescreen shots of the riders, followed by a gentle progression from twilight to sunset, through aerial photography, real and miniature forests, go-motion puppets, and the final studio landing. We soar on the score, and it’s still exhilarating today.

Julie A. Turnock: To judge whether E.T. deserved the Oscar for Best Visual Effects that year against Blade Runner and Poltergeist [and Tron, which wasn’t even nominated!], I always find the effects Oscar arbitrary since by the time it gets to the final ballot, it is the full Academy body voting and they tend to vote for the movie in the lineup they liked the best. But for 1982, E.T. makes sense because it is demonstrating that ILM isn’t just Star Wars. Its artists can make a naturalistic, even mundane setting appear fantastic and magical, and not just a galaxy far, far away. And those effects appearing in the biggest movie of the year just solidified ILM’s position at the top of the effects business, a place they have held since that time.