Thomas A. Christie is the author of The Cinema of Richard Linklater (Crescent Moon, 2008). His other books include The Spectrum of Adventure: A Brief History of Interactive Fiction on the Sinclair ZX Spectrum (Extremis, 2016), Mel Brooks: Genius and Loving It! (Crescent Moon, 2015), The James Bond Movies of the 1980s (Crescent Moon, 2013), The Christmas Movie Book (Crescent Moon, 2011), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Pocket Movie Guide (Crescent Moon, 2010), and John Hughes and Eighties Cinema: Teenage Hopes and American Dreams (Crescent Moon, 2009). He is a member of The Royal Society of Literature, The Society of Authors and The Federation of Writers Scotland.

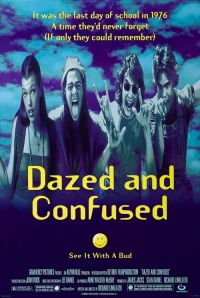

Christie kindly spoke to The Bits about the appeal and legacy of Dazed and Confused.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Dazed and Confused should be remembered on its 25th anniversary?

Thomas A. Christie: Dazed and Confused remains one of the most iconic teen movies of the early nineties, and yet for Richard Linklater aficionados it’s much more than just that. For such an assertively autonomous figure of the indie scene, Dazed and Confused marked a definite move towards a more mainstream sensibility after the startling, bewildering Slacker had burst onto the scene in 1991 and brought his talents firmly into the eyes of the critics. While the film hasn’t garnered as many admirers as the later Before Sunrise, it was undoubtedly a significant film for Linklater in the sense that it laid out many of his existential concerns in an appealingly understated way while also presenting an involving environment that was filled with mostly likeable but always interesting characters. He coaxes some agreeable performances and inspired dialogue from his young cast, established themes that he would return to later in his directorial career, and ensured that he would build confidently upon the goodwill that existed amongst commentators.

Coate: What do you remember about the first time you saw Dazed and Confused?

Christie: I first saw the film at the time of its original release, and while it didn’t quite blow me away to the same extent as the hugely original Slacker had done, it was still a pleasing break from the norm which suggested that Linklater had so much more to say that was valuable and insightful. In particular, I was hugely impressed by his absolute refusal to rely on long-established tropes of the teen movie genre, instead demonstrating an unerring willingness to push the boundaries of the format and present characters who were believable individuals rather than simply walking plot devices. Even in supporting characters who have only a fleeting appearance, Linklater is able to suggest a level of depth and complexity that built admirably upon the genre’s reinvention in its 1980s glory days. It was also a movie that refused to treat teenage concerns in a glib or superficial way. There was no patronizing attempt to reduce the characters’ anxieties about their futures into a series of facile truisms, and many a stereotype was to be subverted before the end credits rolled.

Coate: In what way is Dazed and Confused a significant motion picture?

Christie: One of the most important things about Dazed and Confused is the way in which it’s often held up, quite rightly, as being an example of how the youth cinema of the nineties was evolving rapidly in comparison to the teen movies of the preceding decade. The kids that Linklater is documenting aren’t by any means John Hughes’s brand of teenager, even though an artistic reaction to Hughes is undeniably there. Here we’re seeing a deliberate move away from the class consciousness of filmmakers like Lewis John Carlino, Robert Boris or Joel Schumacher in the eighties, heading instead for the kind of contemplative reflectiveness surrounding young adulthood that would typify the work of Whit Stillman, Amy Heckerling, Kevin Smith and Cameron Crowe heading towards the turn of the millennium. While Linklater’s later Eric Bogosian drama adaptation subUrbia would belong more comfortably within the distinctive mode of Gen-X disaffection movies popularized by filmmakers like Gregg Araki and Larry Clark during the nineties, with Dazed and Confused he was instead tapping into a much more affable, conversational style of teen movie that owed a great deal to the Hughesian ideal of fashioning each young adult character as a living, breathing individual rather than a cliché-ridden archetype (a strategy that Hughes had, of course, employed to brilliant effect in the expectation-redefining The Breakfast Club in 1985). Here we see the usual teen movie stalwarts dragged out and dusted off – the hazing-obsessed jock, the intellectual loners, and so on – only for Linklater to subvert audience anticipation by layering each character with greater profundity and sophistication that might otherwise have been expected at an earlier point in the genre’s history. Like Hughes before him, Linklater obviously believed that each young character deserved to be treated with respect and portrayed as a fully fleshed-out figure with dimension and believable motivations, though he was also to voice skepticism about the high drama surrounding teen life which was presented in some Hughes movies which led him to deliberately portray a more low-key evocation of the subject. As such the result is an admirably nuanced take on the teen movie that was congruent with the fresh wave of nineties entries in the genre which included films such as Metropolitan (1990), Pump Up the Volume (1990), and Mallrats (1995).

Coate: Where do you think Dazed and Confused ranks among Richard Linklater’s body of work?

Coate: Where do you think Dazed and Confused ranks among Richard Linklater’s body of work?

Christie: Certainly among Linklater’s early work, Dazed and Confused occupies an interesting space – more structurally coherent than Slacker, less overtly theatrical than subUrbia, and exhibiting slightly less dialogic polish than Before Sunrise. Given the immediacy of these other films, each of which were very much contemporary takes on modern society and culture, Dazed and Confused uses its nostalgic mid-1970s situation to make some inspired points about the modern day (not least the somewhat poignant, if ultimately mistaken, expectation amongst some of the teenagers that the eighties would turn out to be a golden age of progressive socio-cultural development). Linklater avoids the temptation to turn this period piece into a kind of wistful, idealized consideration of a more innocent age. If anything, there is a subtle theme of “the more things change, the more they stay the same” – a motif which has been threaded through some of his later work – while also suggesting that for each of the kids, the shape of their future will turn out to be limited only by what they make of it.

Coate: In what way did having a cast of unknown and early-in-career actors help (or hurt) the film?

Christie: That’s an interesting question. Certainly many of the performers were complete unknowns, and the film came early in the careers of many of the actors who featured in it, including Ben Affleck, Parker Posey, Milla Jovovich and Cole Hauser, to name only a few. I think, overall, this probably aided Dazed and Confused more than it hurt it; the idea of having a plethora of disparate teenagers celebrating the end of school one spring day in 1976 just seems to work so much better when we have no particular expectation of how a specific big-name performer would likely be approaching a particular role. There is a sense of creative exuberance that would otherwise be denied if the audience is actively expecting a certain actor to play their part in a manner that was distinctive to their usual, expected mode of performance. In later interviews, for instance, Linklater spoke of a desire to cast Affleck in the role of the film’s antagonist Fred O’Bannion precisely because of the actor’s engaging personality, thus ensuring that the character became a suitably larger-than-life figure that didn’t fit the expectations of the mean-spirited school bully archetype. Ironically, while many people best remember Matthew McConaughey in the distinctive role of David Wooderson – an excessively easy-going slacker who is now in his twenties, but still hanging out with high schoolers – as being the standout figure of Dazed and Confused, McConaughey was actually a late addition to the cast, and much of the material to expand Wooderson’s role was improvised.

Coate: How would you describe Dazed and Confused to someone who has never seen it?

Christie: When people ask me what Dazed and Confused is about, my usual answer is that it’s about an hour and a half long – because that’s as good a description as any! One of the things that I’ve always admired about Linklater is that he often refuses to impose a plot on his films; from Slacker to Waking Life, he seems content to meander from one sequence to another in the most casual, free-wheeling way, deftly concealing the fact that every little incident is actually planned out with incredible precision and care. So much thought and consideration, both technical and philosophical, goes into every frame. And so it was with Dazed and Confused, where Linklater takes the basic premise of the last day at school in the mid-seventies and then proceeds to dispense with any conventional narrative thereafter, content to use the environment he has chosen as a backdrop for various incidents rather than attempting to enforce a rigid plot on proceedings. If this suggests a kind of Robert Altman-esque approach to the ensemble comedy-drama, it’s probably fair to say that Linklater shares Altman’s inclination to articulate cultural concerns and social observations as much as he is concerned with the dynamics of juggling multiple characters. For him, one is never subordinate to the other.

Coate: What is the legacy of Dazed and Confused?

Christie: Dazed and Confused was a movie that spoke to teens of all ages, from the freshman to the senior. Some of the characters are coming to terms with arriving at a new school, thus entering a new phase of their lives, while others are struggling with expectations about what they should be striving for from adulthood after they graduate. (Indeed, Wooderson is still struggling with this issue several years after leaving school, proving the old adage that sometimes the most interesting people are those who never really decide what they want from life.) Yet it was also a film that made abundantly clear Linklater’s love of naturalistic dialogue, his aptitude for offering audiences an engaging cinematic milieu, and his talent for presenting appealing, watchable characters. His obvious enthusiasm for period detail was rarely so evident, nor was his undeniable fervor for pop culture and pleasingly meandering observations on the small but important aspects of life. Dazed and Confused was a joy to watch back then, and it is no less so today.

Coate: Thank you, Tom, for sharing your thoughts about Dazed and Confused on the occasion of its 25th anniversary.

---

IMAGES:

Selected images copyright/courtesy Alphaville Films, Austin American-Statesman, The Criterion Collection, Gramercy Pictures, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Thomas A. Christie author photo by Eddy A. Bryan.

- Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)