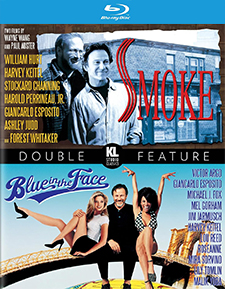

Smoke/Blue in the Face: Double Feature (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Wayne Wang, Paul AusterRelease Date(s)

1995 (September 2, 2025)Studio(s)

Mirimax Films (Kino Lorber Studio Classics)- Film/Program Grade: See Below

- Video Grade: See Below

- Audio Grade: See Below

- Extras Grade: B-

- Overall Grade: B+

Review

Wayne Wang made a name for himself directing low-key slice of life films like Chan Is Missing, Dim Sum: A Little Bit of Heart, and Eat a Bowl of Tea, but his career looked like it might take a turn after the success of his luminous adaptation of Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. While it did feel like a natural progression from his earlier work, it was still a progression into a different scale of storytelling. Yet quietly, in the background, he had already started to work with author Paul Auster on developing the script for another low-key slice of life drama set in and around a Brooklyn tobacco shop: Smoke. Their partnership was so fruitful that they hatched the idea for a spinoff called Blue in the Face while they were still filming Smoke, and they managed to turn it around in a few days using the same sets and many of the same actors. While the two films share the same DNA, each of them takes a drastically different approach in terms of the actual filmmaking: Smoke was carefully planned and scripted, while Blue in the Face was largely improvised on the fly.

Paul Auster’s script for Smoke entangles the lives of several different characters who live in Brooklyn, with the intersection between all of them being the Brooklyn Cigar Co. run by Auggie Wren (Harvey Keitel). Everyone in the film ends up connected to the tobacco shop in one form or another, either as patrons, employees, or those who end up affected by its patrons and employees. In other words, Smoke is really about community. It involves family in all of its forms, both natural and extended, and it demonstrates the way that neighborhoods can revolve around familiar locations that can become a staple part of resident’s lives. The other key characters in the film include Paul Benjamin (William Hurt), an author who serves as a thinly-veiled stand-in for Auster, and Rashid (Harold Perrineau), a drifter whose travails throughout the neighborhood end up affecting everyone else involved.

That’s barely scratching the surface of the extended family in Smoke, however. There’s also the shop’s owner Vinnie (Victor Argo); the mentally disabled janitor (Jared Harris); Auggie’s ex-girlfriend Ruby (Stockard Channing); a troubled young woman who may or may not be Auggie’s daughter (Ashley Judd); a local gangster (Malik Yoba); Augie’s current girlfriend Violet (Mel Gorham); a nearby garage owner connected to Rashid (Forest Whitaker); and a few of the regulars at the shop (Giancarlo Esposito, José Zúñiga, and Stephen Gevedon). And that’s still just a taste of all the myriad characters whose lives are touched by the events that revolve around the Brooklyn Cigar Co. over the span of a few short days.

Despite a handful of major reveals, Smoke isn’t about the big moments, but rather about the small workaday ones. Auster and Wang’s goal was to create the equivalent of a Yasujirō Ozu film set in Brooklyn, so everything unfolds at a leisurely pace in lengthy single takes. Smoke involves the erratic rhythms of real life rather than the cinematic rhythms of conventional dramas. Of course, for classical film critics and theorists like André Bazin and Siegfried Kracauer, reproducing the natural rhythms of life was inherently cinematic—Kracauer even subtitled his book on film theory The Redemption of Physical Reality. Paradoxically, the only artificiality that Smoke embraces is the entirely naturalistic ones that are inherent to the human experience. People’s lives tend to be filled with artificiality of their own creation, and Auster has said that in Smoke, stealing is a form of giving, and lying is a form of truth-telling. Smoke is cinematic storytelling that embraces the personal storytelling that people use to get through life on their own terms.

The creative process for Smoke took place over several years while Wang and Auster hashed out the details, and nearly every last word of dialogue in the film was carefully scripted in advance. That’s in sharp contrast with Blue in the Face, which they conceived of while shooting Smoke and threw it together over the span of a few days. Wang and Auster still contributed their own ideas, along with documentarian Harvey Wang (who shot the video segments that are interspersed throughout the film), but those ideas mostly involved creating situations, setting up the cameras, and letting the actors improvise the actual scenes. That necessitated completely different rhythms than the ones in Smoke, since improvisation leaves less room for space between the words—as soon as one actor pauses, another one usually jumps in. The threads between the characters are also less connected this time around; it’s less of chronicle of their lives than it is a paean to Brooklyn itself.

Many of the actors from Smoke returned for Blue in the Face, including Harvey Keitel, Victor Argo, Malik Yoba, Mel Gorham, Jared Harris, Giancarlo Esposito, José Zúñiga, and Stephen Gevedon. This time around, they were joined by an eclectic group that includes Lou Reed, Michael J. Fox, Jim Jarmusch, Madonna, Roseanne Barr, Keith David (as the ghost of Jackie Robinson!), Mira Sorvino, Lily Tomlin, Michael Badalucco, and RuPaul (because of course RuPaul). John Lurie and his band The John Lurie National Orchestra also make an appearance. As a result, Blue in the Face has an easygoing charm that’s quite different than Smoke—I mean, it features Victor Argo, of all people, singing and playing the guitar, and how more easygoing can you get than that? (He also composed the amusing ditty Dime a Dozen with pithy lyrics like “Girls like you are a dime a dozen, but I’ve got a nickel to spend.”)

Yet however rambling and discursive that Blue in the Face may seem, the same sense of community from Smoke still shines all throughout it. Both films serve as a poignant reminder that true families aren’t born, they’re made. Communities like these only exist thanks to the people who work together to help them thrive. Life goes on and the world keeps moving forward (for good or for ill), but however much that Brooklyn may have changed since Wang made both of these films, that’s a message that never goes out of style.

Cinematographer Adam Holender shot Smoke on 35mm film using Panavision cameras with spherical lenses, framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. This version is based on a 2K restoration that was done back in 2016 by ZAP Zoetrope Aubry Productions, with Kim Aubrey serving as producer. Compared to the dated master that Via Vision used for their 2024 Blu-ray boxed set of both films, the differences are immediately obvious. That one had the signature look of early Mirimax Blu-rays, with the grain minimized and an overall digitally processed look. In this case, it’s like that digital veil has been lifted (although this is definitely a new scan, not just a return to the original raw scans from the older version, since the damage marks don’t line up between the two). The grain has been left alone this time around, which means that fine detail has also been improved. Facial textures and costuming look better resolved, with those extreme closeups of William Hurt and Harvey Keitel during the Christmas story really digging into every pore on their faces. The color balance and contrast also show small improvements, and the grayscale in the black-and-white flashback (or is it one?) during the closing credits is significantly improved—it no longer looks like desaturated color, but rather proper black-and-white.

Adam Holender also shot Blue in the Face on 35mm film using Panavision cameras with spherical lenses, although his work was supplemented by the video segments that were shot by Harvey Wang (no relation to Wayne). The SD video footage was scanned out to film and cut in with the rest of the material, with everything framed at 1.85:1 for its theatrical release. This version is based on a 4K restoration that was done in 2024 by ZAP Zoetrope Aubry Productions, and compared to the master that Via Vision used in their set, the differences are even more dramatic. That one almost looked like upscaled 480p, or else like native 1080p that had been filtered so heavily that it ended up looking like 480p. It was so soft that some of the signs at the back of the store were difficult to read. That’s no longer a problem here, with the results of the new restoration looking comparable to the one for Smoke. There are still some minor damage marks visible, but the instability and frame jumping that plagued the older version have been cleaned up here. It’s a night-and-day improvement.

Audio for Smoke is offered in English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English subtitles. Via Vision’s Blu-ray also offered a 5.1 remix that was a relatively straightforward discrete encoding of the original matrix-encoded four channel Dolby Stereo mix. While that arguably offered more precise steering, this is still a solid Dolby mix, with consistent immersion from the sounds of the city streets and the countryside locations. While the score from Rachel Portman and the various pieces of source music did benefit from the 5.1 treatment, they still sound good enough in 2.0.

Audio for Blue in the Face is also offered in English 2.0 DTS-HD Master Audio, with optional English subtitles. In this case, there was no 5.1 remix on Via Vision’s Blu-ray, so there’s not much difference here. Blue in the Face was also released in Dolby Stereo, but it’s largely a mono mix with stereo music. The dialogue and effects remain firmly anchored to the center channel, and while the music does benefit from having a stereo spread, it lacks the dynamic punch of the music in Smoke. (Side note for Lou Reed fans: the version of Egg Cream that plays over the closing credits is not the same one that he included on his album Set the Twilight Reeling. It’s an alternate mix with a completely different vocals and a subtly different backing track.)

SMOKE (FILM/VIDEO/AUDIO): B+/A-/B+

BLUE IN THE FACE (FILM/VIDEO/AUDIO): B/A-/B-

Kino Lorber’s Double Feature Blu-ray release of Smoke and Blue in the Face is a two-disc set that includes each film on a separate disc, as well as a slipcover. (They’re also offering each film separately, but the two form such an intertwined unit that it’s hard to imagine not wanting both.) The following extras are included:

DISC ONE: SMOKE

- Behind-the-Scenes (SD – 20:51)

- Berlin Film Festival Press Conference (SD – 44:23)

- Interview with Wayne Wang (HD – 22:32)

- Interview with Paul Auster (HD – 23:08)

The only new extra here is an Interview with Wayne Wang, which is moderated by Kate MacKay, associate film curator of the Berkeley Art Museum and the Pacific Film Archive. She explores his background (including whether or not he smokes!) and then asks him questions about meeting Paul Auster and developing Smoke. They also discuss the textural details like production designer Kalina Ivanov’s work in crafting the environment of the Brooklyn Cigar Co., and the process of organizing the structure of the film. Wayne says that the black-and-white version of Auggie’s Christmas story was originally intercut with him telling the story to Paul Benjamin, but it just didn’t work, so they ended up making it into part of the closing credits instead.

The Interview with Paul Auster is an excerpt from the feature-length interview Running Off to the Circus: Paul Auster on Film that Via Vision included on their 2024 Blu-ray release of Smoke. The full interview is a comprehensive look at his entire life and career, including the influence that the cinema had on him as a child. This excerpt narrowly focuses narrowly on the writing of his short Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story and how he and Wang expanded it into a feature film.

The rest of the extras are taken from the previous DVD and Blu-ray releases of Smoke. The Behind-the-Scenes featurette covers the conception and production of the film, featuring on-set and promotional interviews with Paul Auster, Wayne Wang, William Hurt, Harvey Keitel, Stockard Channing, Forest Whitaker, Ashley Judd, Harold Perrineau, and Adam Holender. The Berlin Film Festival Press Conference is from a Q&A session that took place during the 1995 Festival. Participants included Wang, Auster, Keitel, Hurt, Gregg Johnson, Peter Newman, and co-producer Hisami Kuroiwa.

DISC TWO: BLUE IN THE FACE

- Archival Interview with Lou Reed (SD – 18:12)

- Berlin Film Festival Press Conference (SD – 44:23)

- Interview with Wayne Wang (HD – 18:05)

- Interview with Paul Auster (HD – 23:08)

The only new extra for Blue in the Face is a second Interview with Wayne Wang, also moderated by Kate MacKay (although it’s a from a completely different interview session). Wang explains how (and why) the spinoff happened, including why they took such a completely different approach this time. He wanted the music to be front and center this time, so he brought in David Byrne to serve as music supervisor. (The various star cameos, on the other hand, were Harvey Weinstein’s idea.) While Wang’s films have varied quite a bit in terms of form and content, from tightly controlled to wildly improvisational, Blue in the Face felt natural to him despite his inherently controlling nature.

Aside from the Berlin Film Festival Press Conference and the Interview with Paul Auster, both of which are identical to the ones on Smoke, the last extra is an Archival Interview with Lou Reed. It’s an extended version of Reed’s improvised storytelling in Blue in the Face. Auster can be heard in the background prodding him with questions, and it’s interesting to compare his uninterrupted monologue with the way that it’s broken up in the final film.

While it’s nice to have the new interviews with Wang, most of the extras from Via Vision’s set aren’t included here. For Smoke, they produced their own interviews with Harold Perrineau, editor Maisie Hoy, and production designer Kalina Ivanov, and they offered the full-length version of the Running Off to the Circus: Paul Auster on Film interview. They also added a variety of archival extras that aren’t included here, like the 2003 DVD commentary track, two deleted scenes, a second (and briefer) vintage making-of featurette, the theatrical trailer, and a second Q&A with Wang from 2007. For Blue in the Face, they produced interviews with Jared Harris, editor Christopher Tellefsen, and line producer Diana Phillips. They also included archival extras like the 2003 DVD commentary, an interview with Mel Gorham, the theatrical trailer, and a set of outtakes from the improvisational sessions at the cigar shop.

Needless to say, Via Vision has the edge in terms of extras, and it’s not even a close contest. On the other hand, it’s no contest at all between the two in terms of video quality—Kino Lorber wins that one hands-down. After seeing the improvements in their versions, you’ll never want to watch Via Vision’s again. Thus, we have a quandary. If you want the best possible video with the maximum extras, then you’ll just have to pick up both. But that’s not realistic for most people, so if you have to choose only one, I would lean towards Kino Lorber. The film’s the thing, and no quantity of extras can make up for inferior video quality. Your own mileage may vary, however. Yet isn’t it interesting that in 2025, with the streaming wars continuing to rage and uncertain economic conditions that affect production, replication, and distribution of physical media, we’re still in a position where we have to make tough choices between different releases of the same films from competing boutique labels? As frustrating as that situation may be sometimes, it’s better than having no choice at all.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter, Facebook, and Letterboxd).