Anybody know a good screenwriter? Here’s true scenario that would offer a perfect studio pitch.

And it’s a thriller, in a way, with a determined adventurer racing against time to seek justice for a hero from a past generation – one who sacrificed finances, reputation and goodwill to slay a dragon that was, in the long run, perhaps beyond even his reach.

This story is about John Wayne. This story is about Robert Harris. This story is about America and the importance of its cultural maintenance. And, ok, it’s also about personal obsession. Duke Wayne did what he said. No backing out. No cutting corners. No half assed. [Read on here...]

There are those who will argue that a poll be taken today, some 35 years after he died, John Wayne would remain the number one star in the world. In Scott Eyman’s compulsory new book John Wayne, he is described as a thoughtful, literate and savvy motion picture business insider workhorse who was among the first superstars to produce his own films as well as a hell of a fine actor.

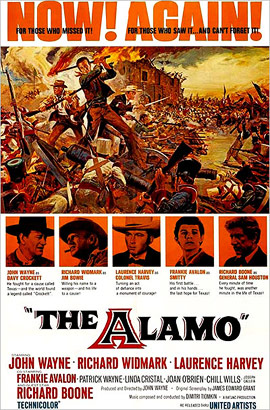

In the late 1940s, a after triumphant rise and astonishing fall resulting from a huge 1930 dud called The Big Trail, Wayne was back on top after being cast in the still influential western Stagecoach and was a contract star for Herbert Yates at Republic pictures when he announced that he wanted to star and direct a film about the 1836 battle of the Alamo. While the subject matter was important to Wayne, according to Eyman, the star also knew to sustain in his particular field he would have to diversify.

“Actors aren’t supposed to have a brain in their heads, but I had enough to know if I was going to stay in the business I was going to have to start moving up the ladder,” he said.

“Actors aren’t supposed to have a brain in their heads, but I had enough to know if I was going to stay in the business I was going to have to start moving up the ladder,” he said.

Yates, after making promise after promise to Wayne, finally passed on the Alamo project and that same day, the Duke packed up his offices and never made another film for Republic, although it was during this next chapter in his life that he would do some his finest and most financially rewarding work – from Red River to Fort Apache and from The Quiet Man for which Wayne directed a scene or two, to The Searchers. So toxic was Wayne’s Alamo project that Warner Brothers, the studio which presented The Searchers and which housed Wayne’s production company Batjac, passed on the project. It didn’t matter. John Wayne was going to produce and direct The Alamo no matter what anyone said.

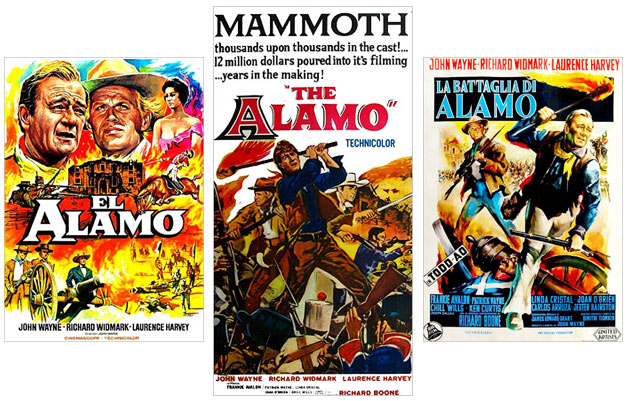

And so in 1956, saying that his career, personal fortune and standing in the business were at stake, John Wayne made deal after deal with United Artists, who invested $2.5 million of the ultimately $12 million budget, Texas oilmen and other independent investors. He began what became a year-long project to build his set and oversaw every single dimension of the film’s creation. Recognizing what a chore it would be to bring his dream project to the screen, Wayne was initially only going to make a cameo appearance in the movie – it was only after United Artists made his starring in the movie a proviso for box office insurance that he decided to play Davy Crockett.

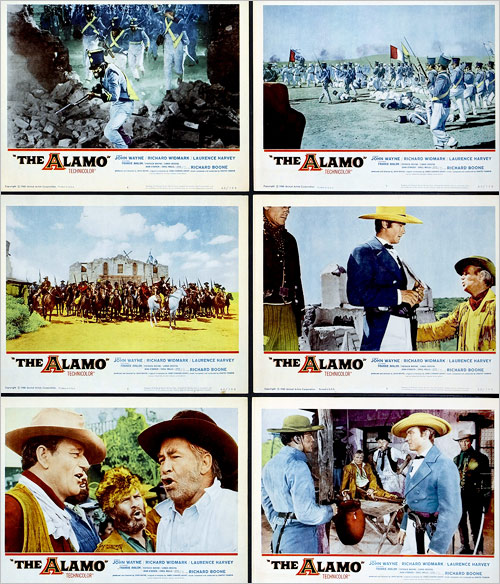

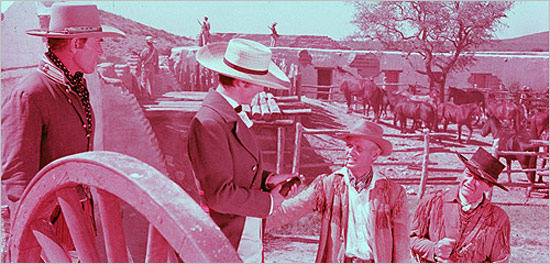

Wayne spared no production expense. Every dollar spent is on the screen. The production was historic and Wayne used his almost, at the time, 30 years in the film business to get the look and accuracy he wanted. The Alamo began production on September 9, 1959 and wrapped December 18 of that same year, some 17 days over schedule. Wayne shot a whopping 560,000 feet of film and lost twenty pounds while filming. He also continued mortgaging everything he owned to pump into the budget, while, at the same time, accepted other funds that would eventually diminish his ownership of the film.

Wayne spared no production expense. Every dollar spent is on the screen. The production was historic and Wayne used his almost, at the time, 30 years in the film business to get the look and accuracy he wanted. The Alamo began production on September 9, 1959 and wrapped December 18 of that same year, some 17 days over schedule. Wayne shot a whopping 560,000 feet of film and lost twenty pounds while filming. He also continued mortgaging everything he owned to pump into the budget, while, at the same time, accepted other funds that would eventually diminish his ownership of the film.

“I have everything I own in it,” Wayne was quoted as saying.

As Wayne was editing the picture, he released a statement which might shed some insight into his determination to make the film at all costs.

“The best reminder of what makes this a great nation is what took place at the Alamo in San Antonio. It was there that 182 Americans holed up in an Adobe mission fought for 13 days and nights against 5,000 troops of the dictator Santa Anna. These 182 men killed 1,700 of the enemy before they were slaughtered because they didn’t think a bully should push them around.”

No grit, John Wayne? Not much.

When the picture opened, it was reviewed as a majestic achievement, with a subpar script. Even with luminaries such as John Ford and William Wyler telling him to edit the script before shooting, Wayne was so loyal to its writer James Edward Grant that The Alamo was shot as written, including speeches that were too long, romantic subplots that were meaningless and an overall sense of, well, cornball.

The Alamo was originally slated by UA to play a “roadshow engagement” with expensive reserved seats, however the type of people who attended those pictures, like Oklahoma! and Porgy and Bess were not necessarily John Wayne fans and it was ironic that a subpar Wayne film North to Alaska, in release at the same time, was outperforming The Alamo at the box office. The Alamo eventually went into general release in both domestic and foreign markets, where it amassed $15 million, which, what with prints, advertising and other costs represented a $2 million dollar loss.

In 1967, Wayne’s company, Batjac, sold all of its final ownership to UA and the studio owned the movie outright. After some thought of putting The Alamo back on screens in those pre home video days, the movie finally premiered on NBC television almost 11 years after it was released.

This is actually how our story begins.

After being created in 1919 by then superstars Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith, United Artists studio was on lean times when it was taken over by attorneys turned producers Arthur Krim and Robert Benjamin in 1951. From that point, it became a Hollywood mainstay – starting with The African Queen and later becoming home to such disparate artists as Burt Lancaster, Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger and Stanley Kramer. Its first Best Picture Oscar was for Marty and the studio would later win for West Side Story and The Apartment. UA was the home for the James Bond films, the Clint Eastwood/Sergio Leone spaghetti westerns and the Pink Panther series. In the 70s, the studio was home to Woody Allen and Last Tango in Paris.

Krim and Benjamin, in 1978, left UA to form a company called Orion with Warner Brothers. The new team at UA immediately sank all the company’s resources into a little film called Heaven’s Gate.

United Artists was eventually sold to an MGM studio to form MGM/UA Entertainment. In 1985 Ted Turner bought the company for $1.5 billion and it was renamed MGM Entertainment Co. Turner then sold the UA portion of the studio to studio investor Kirk Kerkorian, while keeping the pre 1986 MGM film library for himself, which included all pre 1950 Warner Brothers pictures and all from RKO. The new Kerkorian led MGM Entertainment Co. had some produced hits in the 80s, such as the Bond film The Living Daylights and Rain Man but eventually became dormant.

In the early 90s an Italian promoter named Giancarlo Parretti bought the company but soon his bank, Credit Lyonais had to take over due to non payment and began production on new Bond and Pink Panther films. The studio bounced around again, at one time it was managed by Tom Cruise, but, by this point, UA is completely under the MGM logo and was listed as a co-producer of Fame, a remake of an MGM release, and Hot Tub Time Machine.

Today MGM is co financing movies and letting other studios distribute. It distributes those properties to international television as well as its other titles, which include product from, listen up here, United Artists, Orion, American International (Roger Corman pictures), Filmways (Dressed to Kill), The Cannon Group (52 Pickup), The Samuel Goldwyn Company (Sid and Nancy), Polygram (Fargo), Hemdale (The Terminator), Gladden (Fabulous Baker Boys), Castle Rock (Misery) and Island (Trip to Bountiful). It also owns Blue Velvet and Manhunter.

And, either because the classic films known by their MGM brand are now owned by Turner, or because management doesn’t see it as a profitable enterprise or because, after so many ownership groups have held the MGM name, there is no emotional investment, MGM, the all new MGM and owners of all the pictures we’ve been talking about like Sweet Smell of Success or Network or The Fortune Cookie or Annie Hall or, yes, The Alamo does not in any form or fashion have a film restoration department and, as we hear from the front lines, there are no plans to form such at all.

Enter now our digital dreamer, a righter of studio malfeasance – a sort of John T. Chance or Hondo Lane or Ethan Edwards. He restores pictures.

Enter now our digital dreamer, a righter of studio malfeasance – a sort of John T. Chance or Hondo Lane or Ethan Edwards. He restores pictures.

Robert A. Harris, perhaps the world’s most distinguished film preservationist wants to get his hands on The Alamo. He has taken on the big dogs like Lawrence of Arabia, Spartacus and My Fair Lady and using his latest book of digital magic tricks has used modern technology to make them shine like, well, better than new.

Mr. Harris says that The Alamo is the highest profile studio film in the worst shape. He has preached non-stop to all of consequence that every day spent not restoring The Alamo is another day toward that film’s disintegration for all time. And, for some, he’s been saying it for too long.

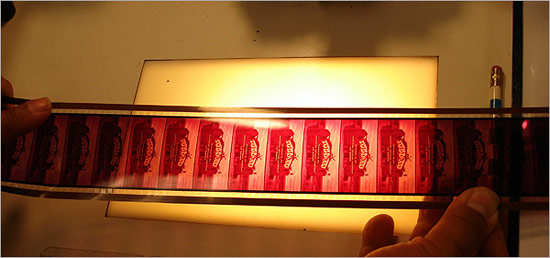

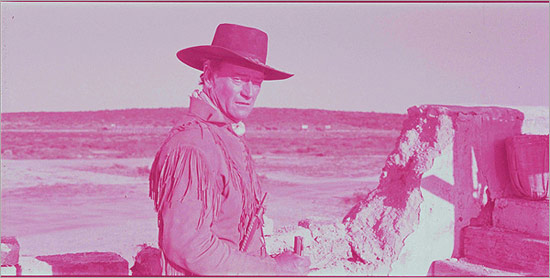

The Alamo’s original negative is faded, missing a high percentage of its yellow layer, which controls blue and contrast, therefore yielding no true blacks and Crustacean-like facial highlights. Any attempt to pump color back into an analogue print turns the skies a muddy green, as yellow is added,” he said. “The negative also has additional damage due to improperly prepared black leader used in negative cutting, which has chemically attacked the emulsion through the two outermost dye layers. The original negative is unusable to make either prints or preservation elements. Add to those problems, a continuously moving discoloration coming in from both sides of the image.”

In an article he wrote for The Digital Bits in 2009 (see link), Harris explained how The Alamo was treated upon release.

“The Alamo was released to roadshow audiences with an original running time of 192 minutes plus Overture, Entr’acte and Exit music. For general release, the film was cut by 30 minutes,” he said.

Harris says that as Wayne himself was in Africa shooting Hatari, a picture into which he immediately went into to help stabilize his finances, Michael Wayne, who was John Wayne’s son and the president of his production company Batjac, along with The Alamo editor Stuart Gilmore shortened the movie themselves.

“Because the 6 track audio could only be either cut or slightly remixed, a detailed fine cut was not an option. Those involved in the cut were led to believe that the extant 70mm prints would be trimmed and resounded, and new printing matrices produced for the 35mm release in the shorter form – but that the original negative would not be harmed or modified,” he said. “That is not what occurred. The original negative and all protection elements, inclusive of the 65mm separation masters, were cut to conform to the new 161-minute length; the trims and deletions were destroyed – and the original 65mm separation masters, which would normally have served as an ultimate backup, were improperly produced and have focus issues.”

“Because the 6 track audio could only be either cut or slightly remixed, a detailed fine cut was not an option. Those involved in the cut were led to believe that the extant 70mm prints would be trimmed and resounded, and new printing matrices produced for the 35mm release in the shorter form – but that the original negative would not be harmed or modified,” he said. “That is not what occurred. The original negative and all protection elements, inclusive of the 65mm separation masters, were cut to conform to the new 161-minute length; the trims and deletions were destroyed – and the original 65mm separation masters, which would normally have served as an ultimate backup, were improperly produced and have focus issues.”

According to Harris, for over 30 years the pre-cut Roadshow version was lost until, in 1991, a lone surviving 70mm print was found in remarkably good condition in a film exchange in Toronto. This version of the film was released both VHS and Laser Disc, both extremely poor cousins of the digital platforms films enjoy today, and was then, well, discarded. Trashed. Dumped. Left for dead.

And Harris, because he’s the best at what he does in the world and because, well, he loves movies, wants this darn thing fixed for audiences to enjoy all over again, even though he understands that Wayne’s epic is most certainly not in the same league as, well, Lawrence of Arabia.

“Unfortunately, that unique remaining 70mm print is now totally faded,” he said, “and to better prepare for its transfer for laserdisc decades ago, it was chemically treated, which exacerbates vinegar syndrome, which eventually destroys film. While modern Eastman elements are robust with a long life expectancy, this is simply not the case for films made before the creation of Eastman 5250 color negative stock in 1961. All Eastman color stocks created before that point fade. Some more, some less, dependent upon a number of technical and storage factors, but the absolute is – they fade.”

So Harris, for longer than he would care to admit, knows the problem and knows how to fix it. And he would be in the laboratory at this very moment strengthening the sparkle in the old Duke’s eyes, but for one thing – the studio who owns the movie, remember them?, refuses to pay for its refurbishing, or allow donations to be made to save the film.

“For whatever reason, they do not see the benefit in restoring their films,” Harris said.

A very recent plea to MGM on behalf of The Alamo by Harris was, well, dismissed.

“We had discussion about the studio finally allowing the use of outside funding, but then they doubled back, and decided to take a ‘wait and see’ attitude. ‘Wait and see,’ for The Alamo, means losing the film in its large format glory. If there is no restoration effort at this time, it means that there may never be a restoration effort,” Harris said. “Several people have raised the concept of going to outside sources for funding. MGM has no interest in this mission, even if the film turns into industrial waste.”

Here would be Harris’ plan for the restoration.

“Our work would take about 10 to 12 months and the final result would be two versions of the film – the original Roadshow and the General Release, both with Overture, Intermission, Entr’acte and Exit Music,” he said. “I could see a major theatrical event projected restored in Digital Cinema in 4K that would come close to replicating the visual and aural splendor of The Alamo as it originally premiered in San Antonio on October 24, 1960, albeit in the general release version. The Roadshow cut of the film would be suitable for home video market, based upon the lower quality of extant elements. The general release version could go the 4k route.”

And the cost for all this? With a grimace, Harris says that it might be as high as $1.5 million.

And the cost for all this? With a grimace, Harris says that it might be as high as $1.5 million.

What? That’s all?

To put it in perspective, the bottled water on your latest Tom Hanks’ picture has a higher budget.

MGM has given no response, other than that from Trish Francis, Sr. VP Library Rights Management. Her message reads:

“Thank you for your email. I have spoken with our Technical Services staff who assured me that the film is not in danger of being lost. They proactively and routinely monitor and assess the condition of the various elements of all of MGM’s films and take steps as needed to protect and preserve them. The film is a valuable part of film history and naturally want to protect it. We appreciate your interest in The Alamo. I will mention your concerns to the appropriate people.”

One can’t imagine them turning down a single or cumulative donation specifically toward the restoration of The Alamo. But, according to Harris, the thought has been given no traction.

“One of the most important ways people know of the extraordinary gift of freedom given to Texas and our nation by those who defended the Alamo is by virtue of this film,” he said. “Although an imperfect representation historically, John Wayne’s work brilliantly portrays that larger than life tale, capturing the hearts and creating lasting memories for all who experience this great film. We are attempting to pull this important film back from the very brink of extinction and preserve it for generations to come.”

All concerned wish there was a quick happy ending – that MGM would fork over a pittance or allow Harris and his band of renegades the opportunity to find the money through other avenues and then allow the master magician to perform his magic.

However, after visiting with Robert Harris, one is reminded of the terrific line Rooster Cogburn says to young Mattie Ross as she heads down to get water from a creek unescorted in True Grit:

“Better for you than whoever comes up against you.”

- Bud Elder

(Photo Credit: Images provided by Robert Siegel)