THE Q&A

Stephen Rebello is the author of Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho (Dembner, 1990). His other books include Reel Art: Great Posters from the Golden Age of the Silver Screen (Abbeville, 1988), Bad Movies We Love (Plume, 1993), The Art of Pocahontas (Hyperion, 1995), The Art of the Hunchback of Notre Dame (Hyperion, 1996), The Art of Hercules: The Chaos of Creation (Hyperion, 1997), and Dolls! Dolls! Dolls! Deep Inside Valley of the Dolls—The Most Beloved Bad Book and Movie of All Time (Penguin, 2020). He has also written for Cinefantastique, Cosmopolitan, GQ, Los Angeles Times, and Playboy.

Rebello kindly spoke to The Bits about Psycho’s appeal and legacy.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): How do you think Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho should be remembered on its 60th anniversary?

Stephen Rebello: On the 60th anniversary of Psycho — its White Diamond anniversary — it should be remembered as the first truly modern thriller, the one that showed us that no movie ghost, wolfman, vampire, zombie is as terrifying, cruel or relentless as a human mind unhinged. It should be remembered as the film that forever changed how Americans went to the movies. That is: at the start of the movie not whenever they felt like dropping in, as was the case before Psycho. It should be remembered as a film that took critics decades to fully appreciate, but only after it became a box-office sensation with audiences. We should remember it as An Event Movie because that’s what Hitchcock’s and Paramount’s iconic promotional campaign turned it into. It should be remembered as the gold standard of psychological horror thrillers because it respects the audience by paying as much attention to delivering memorable, relatable characters, smart dialogue, a gripping plot, and emotional punch as well as jump scares. It should be remembered and celebrated as a movie made by experts who know that what we don’t see but are made to imagine is much scarier than showing everything. It should be remembered and celebrated as a film that has inspired countless imitations, homages, remakes and sequels — official and unofficial — and helped inspire a generation of writers, directors and other moviemakers. It also should be remembered as one hell of a tight, smart, scary, highly entertaining, once in a lifetime classic.

Coate: What do you recall about the first time seeing Psycho?

Rebello: I took a bus downtown after school and sneaked off alone to see Psycho at the Durfee Theater in Fall River, Massachusetts. I wasn’t supposed to do that, so that made the trip all the more forbidden and exciting. In those days, my idea of scary was watching classic old Universal horror movies on TV with my dad or catching up on William Castle, American-International and Mario Bava movies. My parents loved going to the movies and, to them — and to the whole moviegoing world — the name Hitchcock was synonymous with movies that delivered thrills, suspense, intrigue, style, class, high adventure, gorgeous movie stars, Technicolor. The stuff of Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, To Catch a Thief, North by Northwest. Then, there was Hitchcock’s weekly television show with its droll, macabre humor and, sometimes, edgier, twisty plots.

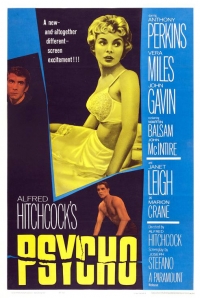

Psycho announced itself as a whole other thing. Its advertising, from the movie trailers to the posters, was stark, sexy, bold, hinting at horror, darkness, something much darker than the usual Hitchcock film. So my parents weren’t about to let me see that movie. Everybody was talking about, whispering about Psycho. I remember pretending to be asleep as my mom drove home Betty, one of her close friends, after they’d seen some glossy Lana Turner or Susan Hayward movie. I guess they’d seen a trailer for Psycho that night and when my mother asked Betty what Psycho was about, she whispered, It’s about a queer! (Wrong but whatever.)

Of course I had to see what the whispering was all about but I knew my parents wouldn’t take me, so I took myself to the movies — on the sly. I remember a long line of buzzing, chattering, raucous people outside the theater. It was like people sound when they’re about to ride a scary roller coaster. There was a life-size cardboard poster of Hitchcock and tape recorded messages warning no one will be admitted into the theater once Psycho has begun. This was a first.

The Durfee was a showplace, a true movie palace with marble floors, chandeliers, and a fish pond in the lobby, but just slightly past its prime and a little seedy. The audience was mostly grownups, people I’d see in grocery stores, in bowling alleys, shopping downtown, even one of my schoolteachers. For some reason, the sound of Psycho made a big impression. It didn’t sound like any movie I’d heard before — so clear, quiet, intimate, except for that jittery, driving, edge-of-the-seat musical score. The audience was spellbound, very quiet. When Janet Leigh reached the Bates Motel, met Norman Bates in the form of Anthony Perkins, went back to her cabin, tore up a piece of paper and flushed it down the toilet, you could hear nervous giggle. You could also feel dread. Anything could happen in a movie that broke the rules

Once the shower scene began, all hell broke loose. People screamed, they were groaning. The lady a few seats away from me covered her mouth with both hands and went running up the aisle toward the exit. I saw my schoolteacher do the same thing. Psycho was a whole other thing. I’m not going to lie. I loved seeing grownups reduced to acting like scared kids. But when I went back and saw the movie for a second time and the audience was much smaller, I loved the movie. It packed a punch and had such power.

Coate: In what way is Psycho a significant motion picture?

Rebello: [In addition to some of the points I made in answering your first question], it was also significant for shifting Hitchcock’s reputation from smooth, suave, expert thriller-maker to the man who outdid everyone else when it came to horror. He never fully recovered. Every movie he made after it lived or died not by whether that movie was as good as, say, Notorious or Strangers on a Train but also whether it was as scary as Psycho. Talk about a double-whammy for an artist who wanted to keep growing, changing, innovating with the times. In some ways, Psycho paralyzed him as much as it liberated him.

Coate: Where do you think Psycho ranks among Alfred Hitchcock’s body of work?

Rebello: I’d put Psycho among the Hitchcock’s five best that also include Notorious, Rear Window, Strangers on a Train, and Vertigo, followed by The Birds, Shadow of a Doubt, North by Northwest, The 39 Steps, and The Lady Vanishes.

Coate: Can you discuss Hitchcock’s choice in producing Psycho in black-and-white after doing several films in color and the previous few in VistaVision?

Rebello: It wasn’t a choice. The bosses at Paramount thought Hitchcock had been spending far too much money on Rear Window, To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much and wanted to curb him, especially when both The Trouble With Harry and Vertigo underwhelmed at the box-office. They told him point blank that they didn’t like the Psycho project and refused to give anywhere near his usual production budget. Hitchcock himself was nervous about the picture and decided to do Psycho quickly, inexpensively, in black-and-white but with all his usual meticulous planning. He shot it with his Alfred Hitchcock Presents crew, kept the budget low and even considered, at one point, cutting it and playing it off as a special one-hour TV show. We all know how it turned out, of course, but according to many of Hitchcock’s colleagues, when he said that he chose black-and-white for Psycho so he wouldn’t have to show blood? Not quite true.

Coate: What is the legacy of Psycho?

Rebello: Psycho blew wide so many censorship barriers, created so many iconic moments, reinvented so many tropes of the genre and left such a mark on audiences, let alone filmmakers, that it opened the floodgates for artists who truly understood what a milestone it was and built on its foundation — like Roman Polanski with, say, Repulsion, Nicolas Roeg with Don’t Look Now, William Friedkin and The Exorcist, Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia, Bong Joon-Ho’s Mother, stuff by George Romero and many more. It also paved the way for ambulance chasers and much lesser talents who only prove that imitations may be fun and flashy but at the end of the day, they’re too derivative to become legendary.

The movie has become so ingrained in the collective conscious and unconscious that it’s impossible for many to hear the name “Norman Bates,” to hear shrieking violins, to spot an old Victorian-style house, to step into a shower — let alone a shower in roadside motel — without thinking of Psycho. Today, the shocks and twists of the movie may be seem tame and refined in comparison to some of the cinematic bloodbaths we’ve had since. But its characters, performances and famous set-piece scenes are indelible and its legacy is indelible. How many other films still haunt our dreams 60 years later?

Coate: Thank you, Stephen, for sharing your thoughts about Psycho on the occasion of its 60th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy New York Daily News, Paramount Pictures, Shamley Productions. Universal Studios, Universal Studios Home Entertainment.

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were regional newspaper coverage and trade reports published in Billboard, Boxoffice, The Hollywood Reporter, and Variety.

All figures and data included in this article pertain to the United States and Canada except where stated otherwise.

SPECIAL THANKS

Don Beelik, Mark Lensenmayer, Stephen Rebello.

IN MEMORIAM

- George Tomasini (Editor), 1909-1964

- John L. Russell (Director of Photography), 1905-1967

- Bernard Herrmann (Composer), 1911-1975

- Alfred Hitchcock (Producer-Director), 1899-1980

- Joseph Hurley (Art Director), 1914-1982

- George Milo (Set Decorator), 1909-1984

- John McIntire (“Sheriff Al Chambers”), 1907-1991

- Robert Clatworthy (Art Director),1911-1992

- Anthony Perkins (“Norman Bates”), 1932-1992

- Robert Bloch (Novel), 1917-1994

- Martin Balsam (“Det. Milton Arbogast”), 1919-1996

- Saul Bass (Title Designer),1920-1996

- Janet Leigh (“Marion Crane”), 1927-2004

- Joseph Stefano (Screenplay), 1922-2006

- John Gavin (“Sam Loomis”), 1931-2018

-Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)