Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Jurassic Park for the first time?

Awalt: I’m a very emotional filmgoer, and I can still vividly remember the feelings Jurassic Park triggered in me. Watching the film the first time was an adrenaline shot to the frontal lobe, as it plays to so many emotional areas in its viewers. It’s awe-inspiring, terrifying, hilarious, and damned exciting throughout its running time.

You care for its characters — despite critics calling them “cardboard,” as they once did with Indiana Jones, these characters have the right shading for a plot-centric film and winning performances by likable actors so that audiences are fully engaged with them.

One personal note about my first viewing of the film: I stupidly had the tips of my sneakers resting on a crossbar on the bottom of the theater seat in front of me (this was pre-stadium seating and luxury chairs), and the person occupying it got so scared by something in the film, they jerked back violently in their chair and pinched the tips of my toes! Hurt like hell, but the pain couldn’t tear me from the movie for long.

Matessino: I can remember a palpable sense of anticipation on opening day, June 11, 1993. I saw it at the AMC 14 in Burbank, which was state-of-the-art at the time. But a few years later it was torn down and they built a new 16-screen complex across the street that has a Dolby Cinema. That whole area has changed and it’s basically right where the T-Rex chased people down the street in The Lost World. Anyway, this was in the last days before the Internet when you had to go to the cinema to buy the tickets in advance and then get on a ticket holders’ line. If you wanted a good seat, you got there early and waited. Consequently a lot of anticipation built and people on line started talking to each other. But now a lot of this social aspect of moviegoing has vanished. We click-click our mobile devices and get an assigned seat, scan our phone at the door and quietly walk to our recliner chair sometimes without speaking to another person other than whoever we’re with. And if there is a line to ever wait, everyone is staring at a phone the whole time. The theaters are nicer now but the social experience has changed, and for some reason when I reflect back on it, the opening day of Jurassic Park comes to my mind very vividly.

McBride: I felt like almost everyone else — overwhelmed by the wonderment of it all. I found in my research for Steven Spielberg: A Biography (1997), which I began working on in 1993, that in the Russian shtetlach from which some of Spielberg’s ancestors came, there often was a character known as “The Wonder Man.” He was a fellow who told stories that engaged people’s imagination with a sense of wonder and helped lift them out of their daily troubles. Spielberg is certainly “The Wonder Man” for modern movie audiences, even if he is much more as well, as a dedicated and ambitious maker of historical films and other dramas. But seeing the dinosaurs interact with humans so credibly in Jurassic Park was, and still is, pure cinematic magic of the highest order. The process by which this was created is shown vividly in an excellent documentary, John Schultz’s The Making of “Jurassic Park” (1995). I recommend that for anyone who wants to know how this cinematic advance from the old forms of stop-motion animation was achieved.

But naturally it’s a shame the old forms were rendered “obsolete” (a line uttered during production by stop-motion animator/dinosaur supervisor Phil Tippet and incorporated into the film by Spielberg), since they were so literally wonderful in their way, as the films of Ray Harryhausen and others demonstrate. Even though Jurassic Park holds up very well, today CGI has come a tremendous distance technically. But it’s so overused and so dominant in American filmmaking that I hope I never see another CGI effect again. Or at least not so many that they swamp the storytelling and become an end in themselves, as is too often the case today. Large-scale features today are mostly cartoons. The audience in effect is saying what the psychologically unhinged Blanche says in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire: “I don’t want realism. I want magic!” People not surprisingly find the modern world almost unbearable and desperately want to escape, even more than they did in the Depression era. We’ve lost a lot with this overindulgence in fantasy. Not everything needs to be “realistic” — a malleable concept in any case — but not as much of our entertainment should be purely fantastical and escapist.

Coate: In what way is Jurassic Park a significant motion picture?

Awalt: I think some critics use this to take away from the quality of Jurassic Park as a movie itself, but without argument the most significant part of Jurassic Park so far as its influence on cinema is its epochal visual effects work. Audiences up to 1993 had never seen anything like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, having become accustomed to all manner of once innovative special effects makeup, puppetry, and stop- and go-motion animation. But Dennis Muren and his team were giants standing on their own broad shoulders with the strides they made from computer-generated visual effects throughout the 1980s — from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan to Young Sherlock Holmes, Willow, The Abyss and Terminator 2. Jurassic Park was the first time identifiable, non-fantasy creatures truly lived and breathed on the screen despite being composed of nothing more than binary code and polygons. The dinosaurs then and even now feel wholly real, so much so that I’d argue the digital effects in Jurassic Park still stand superior to some CG-animated films made in this era, twenty-five years on.

It’s too easy to discount the physical special effects in Jurassic Park alongside the CG dinosaurs, however, and I think that’s another part of the film’s secret of enchantment. Stan Winston and crew’s full-scale dinosaur creations are every bit as important as the CG in the film, as they’re an integral part of the illusions. Without them, the film would not be complete.

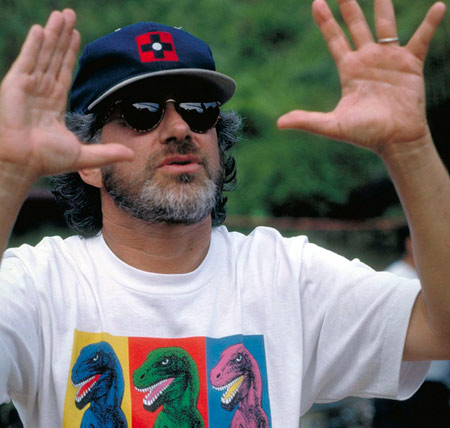

Finally, it takes a filmmaker as deeply imaginative, but also technically savvy as Steven Spielberg to orchestrate these elements and bring them all together into a cohesive whole that works with his intricate vision as a storyteller, in both moments and big picture. There are other filmmakers who would have made wonderful adaptations of the Crichton book, no doubt, but the project landed in the right, highly skilled hands, heart and imagination.

Matessino: Its greatest significance is probably in the field of computer generated visual effects. There was a lot of buzz about that at the time, and the brilliant thing is that story itself was about a breakthrough technology making it possible to do something that could never been done before. So there was a clear parallel between the experience of the audience and the experience of the characters within the story. There are a lot of elements that suggest the whole thing is a movie within a movie, and it’s something the audience gets to be in on, perhaps subconsciously. This brings me back again to the experience of seeing the movie on opening day because I remember being aware of this aspect of the experience. There was also the digital sound, which itself was groundbreaking. So at the technical level this was a very significant picture, not just in how movies would be made, but it also played a role in how cinemas would change, and also in how movies would be marketed. It’s a textbook summer blockbuster.

McBride: For the reasons I outlined [earlier in the interview], the film is historically significant for its technical advances and achievements. But too often people talk about Spielberg films purely in terms of technology. He is a master craftsman, but he is also a great storyteller and a marvelous director of actors. That latter talent is seldom remarked-upon, but Anson Williams, who was a youthful actor in a Spielberg TV show and went on to become a director himself, told me, “Any director can get a great performance out of Al Pacino. Not every director can get a great performance out of a rubber puppet.” The dramatic spine of Jurassic Park is not the confrontation with dinosaurs per se but the Sam Neill character’s irrational hatred for children and how he overcomes it in the course of the story. That’s a quintessentially Spielbergian theme. The Neill character becomes the protector of the children beautifully played by Joseph Mazzello and Ariana Richards, and they and he and the Laura Dern character silently form a symbolic new “family” at the end. Most viewers seem to miss that running theme (people often don’t notice silent storytelling), or if they do, many reject it, since our culture too often hates children. Spielberg’s work was long obsessively concerned with irresponsible father figures. Oskar Schindler is another, and in that film too he learns to become responsible for his “family” of “Schindler Jews.”

In more recent years, Spielberg has put some of his family demons to rest by reconciling with his father, Arnold, who is still with us at the age of 101. In my 1997 biography I revealed that Arnold, with whom I had a rare interview, was unfairly blamed for the breakup of the family (as Steven now realizes, and as his late mother, Leah, admitted) and that Arnold, a computer pioneer and amateur filmmaker, helped guide Steven in his early filmmaking. That theme of the irresponsible father was brought to a degree of rest with the depiction of the relationship between John Quincy Adams (Anthony Hopkins) and his late father, John Adams, in Spielberg’s superb and underrated 1997 film Amistad. In some other late films Steven has gone back and forth between dealing with irresponsible father figures and mother figures (though there was one of those in Sugarland Express as well, not long after his parents’ divorce, which so traumatized him). An artist never quite escapes his obsessions, but Spielberg has evolved a lot over the years as he ages. He’s been in something of a slump the last few years but undoubtedly will recover.

Coate: In what way was Spielberg an ideal choice (or not) to direct, and where does the movie rank among his body of work?

Awalt: It takes a filmmaker as deeply imaginative, but also technically savvy as Steven Spielberg to orchestrate [all of the] elements and bring them all together into a cohesive whole that works in both moments and big picture. There are other filmmakers who would have made wonderful adaptations of the Crichton book, no doubt, but the project landed in the right, highly skilled hands, heart and imagination.

Matessino: I remember Siskel & Ebert appearing on David Letterman’s show to discuss that summer’s movies and they gave Jurassic Park two thumbs-up, but said “just don’t go in expecting Jaws.” And that’s probably a fair assessment. Obviously Jaws, Raiders, E.T. and Schindler’s List are considered Spielberg’s greatest and most successful films, so while Jurassic Park might not have quite hit that level, it’s actually the Jaws for that generation. And Spielberg was the perfect choice to direct it. He had a long history with Michael Crichton that went back to 1971: when Crichton visited Universal at the time when The Andromeda Strain was being made, it was a young Spielberg who was asked to show him around the lot. Later they did ER together. Steven Spielberg has a passion for and fascination with technology, but technology tends to fail in the stories he tells and some of his film have themes that warn of the dangers of its misuse or our complacency about it, most recently Ready Player One. So Jurassic Park was perfect for him in that it was a way for him to revisit the same genre of Jaws while also addressing some of these technology themes as well as themes about family and procreation. And he got to do all of this through a movie that itself was a technological breakthrough.

McBride: One of my director friends was also competing for the job of directing this film version of Michael Crichton’s novel, but he wanted to portray the Richard Attenborough character, the elderly theme-park creator, in a darker, more satirical light. My friend felt that Spielberg would identify too much with that character as a creator of theme park attractions, even if they run amok, and that is what happened to the film. But Spielberg’s ambivalent fondness for that character helps make Jurassic Park a personal film, along with the reconstituted-family theme. You could call the Attenborough character the “irresponsible grandfather figure.” Spielberg does show a certain satirical distance from the character from time to time — Spielberg’s advanced penchant for parody is seldom recognized — but clearly he loves the old guy for bringing dinosaurs to life as he himself does in the film, regardless of the consequences (and he learns a lesson from that too, the familiar one from horror films of the danger of man tampering with nature). The fact that the character is played by an important film director is no accident. After Attenborough won the Directors Guild of America Award in 1983 for Gandhi over E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, he generously, and accurately, told Spielberg, while passing his table, that he should have won.

And certainly the film Spielberg made of Jurassic Park is miles ahead of the Michael Crichton source novel artistically, which is partly due to the smoothly efficient script David Koepp wrote with Crichton that brings out more human values latent in the story. Crichton does not know how to write people, and though his scientific discussions are often fascinating (if sometimes mumbo-jumbo), his writing style is flat and pedestrian. It’s astonishing what a semiliterate piece of junk his sequel novel The Lost World is, and the 1997 film sequel version is one of Spielberg’s few truly bad films. The director’s heart was not in it, and it shows; he only made it because he couldn’t bring himself to let someone else do the first sequel, as had happened with the Jaws sequels. But as Crichton said of Spielberg in 1995, after they made Jurassic Park, “He is arguably the most influential popular artist of the twentieth century. And arguably the least understood.”

Coate: By the time of the production of Jurassic Park, Spielberg’s team seemed a well-oiled machine with numerous long-time collaborators (Kahn, Williams, Kennedy/Marshall, ILM, etc.). In what way did Jurassic Park benefit from this type of collaboration?

Awalt: I’m not entirely sure the film could’ve been made as we now have it if not for the team of collaborators who’d been working together for over a decade.

Matessino: When you put together the right football team, you keep it intact if they’re on a winning streak. So Jurassic Park benefited entirely from this “well-oiled machine,” as you describe it, not just by making the movie itself, but in Amblin acquiring the rights to such a lucrative property. That was a big boon for the company and the success of Jurassic World two years ago demonstrated that it was a pretty good investment. Also, Jurassic Park had to be made in a specific time window because Spielberg immediately left to make Schindler’s List right after. So he needed his reliable team to handle the postproduction, which was done in conjunction with Lucasfilm, and coordinated by Kathy Kennedy, who is now its president. So I think this team of filmmakers was essential in making Jurassic Park a success.

Coate: How does the Jurassic Park movie compare to the novel on which it was based?

Awalt: The film is famously known for having more heart, more character, more humor than the novel itself. The book, as are most Michael Crichton novels, is very technical, wherein Crichton and David Koepp’s script is lighter on its feet when imparting the technobabble integral to our understanding the plot. Casting Jeff Goldblum in particular was a master stroke to help with such exposition, not only given his proved, deft and winning verbal patter with such material (e.g. David Cronenberg’s The Fly from 1986), but with the singular character Goldblum breathed into his portrayal of Dr. Ian Malcolm.

And of course Richard Attenborough’s John Hammond is avuncular and despite his unchecked enthusiasms and ultimate folly, miles apart from the more simplistic and wholly self-serving and corrupted Hammond of the novel. You can’t imagine the film’s Hammond meeting the same fate — let alone deserving of it — as the Hammond of Crichton’s novel.

Ultimately, it is Spielberg’s personality, Koepp’s playfulness as a screenwriter and the charming ensemble cast that helps make Jurassic Park as a film a more multifaceted affair. The movie has heart, but it also has moments in it that can rip your heart out. I think that very thing applies to many of Spielberg’s adventure-thrillers.

Matessino: The film is very streamlined in the way any good adaptation should be, and from a character standpoint I think the film made all the right choices, from making the Hammond character sympathetic to reversing the ages of the children, to making the Ellie Satler character a contemporary and love interest of Alan Grant rather than his young intern — this gave the film a way to address the themes about family and parenting. As far as the dinosaurs were concerned I have to admit that all of the scenes I was hoping to see did not appear in the film, and some of them were even drawn as preproduction art. But they all eventually appeared in the sequels. There is also a lot more science in the novel, which is Crichton’s forte, but that was also streamlined in the film, but in the correct way.

Coate: How do you think the subsequent Jurassic movies stack up against the original movie?

Awalt: While the sequels all have their delights, I don’t know that anything stacks up to the original film. It’s one of those movies that just has all the right elements to it. That said, I do think that The Lost World has one of the greatest set pieces of Steven Spielberg’s entire career in it, the impossibly tense and terrifying sequence where the T-Rex push the conjoined lengths of trailers over the edge of a cliff, causing Julianne Moore’s character to land on an increasingly fragile pane of glass that’s the only thing keeping her from falling to her death in a chasm far below. It’s one of the most grueling, punishing sequences of suspense you could watch in any film, expert in every note. Without a doubt on par with the roadside T-Rex attack in the original film.

Matessino: As with most multi-film series, I don’t think the original can be touched. The Lost World is a film Spielberg has admitted he was not particularly happy with, but it was successful and there are many good things in it. It takes the idea into a darker, grittier place. Joe Johnston’s Jurassic Park III takes a lot of criticism, but it’s a short movie that delivers the dinosaur action and you get in and out quickly. It’s not a bloated self-important lumbering sequel, and I happen to appreciate that. Jurassic World relaunched the series in a spectacular way, giving the current generation their Jurassic Park movie.

Coate: What is the legacy of Jurassic Park?

Awalt: Jurassic Park is beloved as a movie, so much so that its legacy lives on to this very day in the Jurassic World franchise. Clearly people can’t get enough of these stories, characters and majestic and monstrous beasts from prehistory that hubris has wrought and brought into our modern world. I’m personally very excited to see Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, if only because as history over the last twenty-five years has shown us, it’s going to be one helluva time at the movies this summer.

Matessino: There’s a new film in the series opening, so we’re living in the legacy. Audiences still watch Jurassic Park, which is the greatest legacy for any movie when it’s twenty-five years old. It will forever be marked by film historians as a flashpoint for digital effects and digital cinema and an essential movie in studying the career of Steven Spielberg.

Coate: Thank you — Steven, Mike, and Joseph — for participating and sharing your thoughts about Jurassic Park on the occasion of its 25th anniversary.

--END--

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy Amblin Entertainment, Universal Pictures, Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Home-video collage by Cliff Stephenson. DTS logo artwork courtesy Bobby Henderson. DTS discs photo courtesy Blaine Young.

SOURCES/REFERENCES

The primary references for this project were regional newspaper coverage and trade reports and articles published in Billboard, Boxoffice, The Hollywood Reporter, Variety and Widescreen Review. Selected details referenced from BoxOfficeMojo.com, CinemaTour.com, CinemaTreasures.org, and Movie-Theatre.org. All figures and data included in this article pertain to the United States and Canada except where stated otherwise.

SPECIAL THANKS

Jerry Alexander, Brad Allen, Bernie Anderson Jr., Steven Awalt, Claude Ayakawa, Mike Babb, Jim Barg, Don Beelik, Martin Brooks, Mark Campbell, Raymond Caple, Jonathan M. Crist, DATASAT Digital Entertainment, Nick DiMaggio, Mike Durrett, Mitchell Dvoskin, John Eickhof, Monte L. Fullmer, Aaron Garman, Paul Gordon, Nicholas Grieco, Steve Guttag, Edward Havens, John Hazelton, Bobby Henderson, Manny Knowles, Bill Kretzel, Ron Lacheur, Ronald A. Lee, Mark Lensenmayer, Victor Liorentas, Dave Macaulay, Stan Malone, Adam Martin, Mike Matessino, Joseph McBride, Gordon McLeod, Brad Miller, Chris Mosel, Tom Mundell, Gabriel Neeb, Scott Neff, Tim O’Neill, Jim Perry, Tom Procyk, Joe Redifer, Lyle Romer, Greg Routenburg, Daniel Schulz, Jesse Skeen, Cliff Stephenson, Terry Lynn-Stevens, Chris Strobel, Sean Weitzel, Jason Whyte, Blaine Young, Vince Young, and a huge thank-you to all of the librarians who helped with the research for this project.

IN MEMORIAM

- Richard Kiley (“Jurassic Park Tour Voice”), 1922-1999

- Bob Peck (“Muldoon”), 1945-1999

- Stan Winston (Live Action Dinosaurs), 1946-2008

- Lata Ryan (Associate Producer), 19??-2008

- Greg Burson (“Mr. D.N.A. Voice”), 1949-2008

- Michael Crichton (novel, screenplay), 1942-2008

- Jophery Brown (“Worker in Raptor Pen”), 1945-2014

- Richard Attenborough (“Hammond”), 1923-2014

-Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)