CHAPTER 10: MEMORABLE SCENES

Joseph McBride: The sock hop scenes are marvelously charged with energy, humor, and nostalgia. The drag race and crash at the end—based on an incident that changed Lucas’s life when he was in high school—is powerful. But really the film is all of a piece, and the cruising scenes that dominate the movie are all beautifully done. The cars gleam like precious gems, and the film is a funny paean to and something of a satire of the American obsession with car culture. The cars compete with the actors as characters, much as the robots and space ships do in the Star Wars movies. I found it intriguing on a recent viewing that American Graffiti, unlike most films today, takes the time to linger on emotional scenes in its last parts rather than getting more frenetic.

Ray Morton: The cruising “ballet” of cars that comes soon after the opening scenes at Mel’s…. Milner and Carol’s shaving cream and tire deflation “revenge” on the girls in the Cadillac…. Milner and Carol’s walk through the junkyard…. Curt’s walk through the empty halls of his high school and his subsequent encounter with Mr. Wolfe…. Ripping out the axel of the police car…. The liquor store scene…. Curt’s meeting with Wolfman Jack…. The climactic race between Milner and Falfa…. Curt seeing the white T-Bird as he looks down from the airplane…. The “where are they now” legends that appear just before the end credits.

John Cork: The Toad trying to park his Vespa at the film’s opening breaks me up every time. The look on John Milner’s face when Carol gets into his hot rod, the reaction of Curt when Joe, the head of the Pharaohs, mentions a “blood initiation,” the carefully-planned out “let’s see other people” talk that goes sideways between Steve and Laurie, and Debbie talking about The Goat Killer as The Toad tries to suppress his rising fear.

Ray Morton: Curt’s meeting with Wolfman Jack. It’s a sweet scene (literally and figuratively--“Sticky little mothers….”) with a lovely twist at the end. It also perfectly summarizes the message of the movie—if you want to make something of your life, you have to leave the comfort and safety of home and head out into the big wide world. It’s the exact message that Curt needs to hear. That all of us need to hear.

John Cork: My favorite scene is Curt going to the radio station to get a request out for the girl in the T-Bird, and the complex moment of honesty as he realizes the man to whom he’s been talking is the legendary and glamorous Wolfman Jack, and the realization that The Wolfman is just a local DJ who never made it out of the small town, whose dreams and ambitions are melting away each night like the popsicles in the station’s broken fridge.

CHAPTER 11: SUCCESS!

William Kallay: [During the Q&A at the Academy’s 25th anniversary screening,] George Lucas was his usual self and did not make a big deal with how successful his film was. He spoke about how Universal and Ned Tanen were not enthusiastic about American Graffiti and that there was a desire to simply put it on TV instead of releasing it in theaters. As the legend goes, producer Francis Ford Coppola stepped in and wanted to buy the movie. Tanen relented and, of course, the film became one of the biggest hits of all time.

Peter Krämer: The reason I became so interested in the careers of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg was that they managed (separately and jointly) to make a string of massive hit movies across the 1970s and 1980s (and beyond). It was (and is) so rare that filmmakers succeed at the box office with several films in a row, and it is even rarer that they do so with films which are based on original stories that they have come up with and developed themselves (often with the help of other writers). Throughout American film history most films have flopped at the box office, and most hit movies have been based on previously-published material (that is they have been adaptations of novels, stage musicals etc. or they have been sequels, prequels, spin-offs etc.). But here is American Graffiti, only Lucas’s second film (the first one having been a terrible flop); the story is largely based on his own youth and he co-wrote the screenplay. What is more, unlike almost all previous big Hollywood hits, Graffiti had no stars and a, by the standards of the time, tiny production and marketing budget. And yet it became one of the highest-grossing films in Hollywood history up to this point, while also being enthusiastically received by critics, eventually coming to be recognized as one of the best American movies of all time. I would call that very noteworthy indeed. Of course, it is also the case that the success of American Graffiti enabled George Lucas, whose film career might otherwise well have ended in the early 1970s, to make Star Wars—and that film in turn changed American and indeed global cinema culture forever.

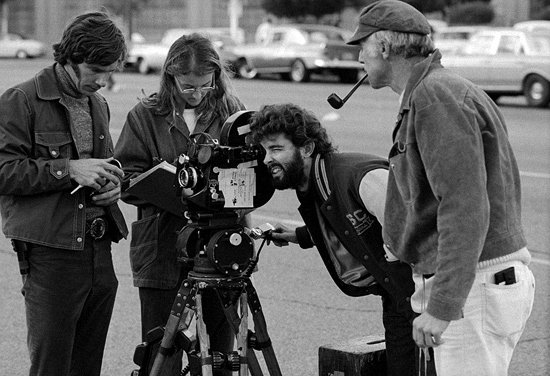

Beverly Gray: Writer-director George Lucas, not yet thirty, used the events of one hot summer night in a Northern California town to capture the essence of being a teenager in 1962, before Vietnam became the nation’s predominant nightmare. The movie, shot in Petaluma, California (standing in for Lucas’s own Modesto) over the course of twenty-eight nights, cost a mere $775,000. After its release in August 1973, it racked up $115 million in domestic box office, then went on to be nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Ray Morton: Not bad for a little movie that cost under a million bucks to make and that the studio didn’t want to release.

CHAPTER 12: SIGNIFICANCE AND INFLUENCE

Gary Leva: The film was hugely influential, particularly in two areas. The first is the use of popular songs instead of a score. The idea of scoring an entire film with Top 40 songs was revolutionary. No one had ever used more than a handful of songs in a film. In fact, the term “Song Score” hadn’t even been invented yet. Today this is commonplace, but it all started with American Graffiti.

Ray Morton: The Graduate was the first significant film to use pop music as a score, but apart from “Sounds of Silence,” the songs in The Graduate were composed for the film, or were at least introduced in the film. And all of the music in The Graduate were written by the same person and performed by the same artists. Graffiti was the first significant film to use existing pop songs by a multitude of artists as score, an approach to music in movies that eventually became standard.

Gary Leva: The second influential aspect of the film is the way the story is told. Rather than focusing on a single protagonist, Graffiti follows four separate stories that rarely intertwine until the film’s final scene. In fact, this unconventional structure is one of the reasons the script was initially turned down by the studios. Today, this kind of storytelling is commonplace—Pulp Fiction is a good example.

Rob Hummel: The reason John Bailey and Lawrence Kasdan wanted to shoot Silverado in Super Techniscope [aka Super-35] was because of films like American Graffiti, THX 1138 and Once Upon a Time in the West and the great depth of field they were achieving in the Techniscope format.

John Cork: It is incredibly complex in its structure, filled with brilliantly understated comic performances that launched the careers of oodles of stars. Its staggering success gave cinema some of the most talented and influential behind-the-camera creators in the history of the medium. Although it was not the first “American teen coming of age” film of that era (the success of Summer of ’42 and The Last Picture Show, both released in 1971, paved the way for American Graffiti to get made), it is the one that defined the genre, and it remains unabashedly the best.

Ray Morton: Along with Summer of ’42, it made coming-of-age movies a viable genre, and along with the stage musical Grease, it was one of the pop culture items that kicked off the 50s nostalgia craze of the 70s.

Joseph McBride: For one thing, it’s still Lucas’s best film all these years later. It showed he could make movies about real life and about people’s complex dilemmas. He mostly abandoned that mission (Capra’s comment aside). Lucas kept claiming that when he made money, he would go back to making little films like Graffiti and his first feature, THX 1138, but of course he never has. The Star Wars saga was a Faustian bargain that helped ruin him artistically though not financially. American Graffiti shows what he could and should have been.

Ray Morton: As cinema, it’s a classic—pure and simple. And, as my friend Brian observes, Graffiti has had a lasting impact on car culture, both in the U.S. and around the world: “The impact was nationwide, and spread to Europe and Japan at the least, (piggybacking somewhat) on GIs bring U.S. hotrod culture with them to bases around the world. In Europe there are still “Shine & Show” or “Show & Shine” gatherings for vintage cars and hotrods. Foreign roads really don’t lend themselves to “cruising,” but across the U.S., “Cruise Nights” at fast food restaurants or large parking lots popped up and continue to this day. “Show & Shine” car shows also still happen across the U.S. Some are spontaneous, some are sponsored by local car clubs. Some clubs went so far as to create a DJ trailer to play oldies at the gatherings. It’s a chance for car guys to bring out their pride and joy and show them off, to each other, and the next generation…. I’m not a car guy, but my lifelong friend Brian Finn is. He’s also a huge Graffiti fan and he reminded me that the film gave a significant real-life boost to John Milner’s trusty ride. As Brian says: “I recall hearing that a car magazine writer, after seeing the film, had only one thing to say about it: …’the price of yellow deuce coupes just went way up.’ The Ford ’32 coupe was always a popular car, and (became one) of the first hot rods, but Graffiti launched one yellow five window into icon status. In the film, the ‘Deuce Coupe’ is essentially a character, a supporting actor with no lines. It just has to be seen in the frame, to have an impact.”

Beverly Gray: American Graffiti had personal resonance for Ron Howard, as well as for audiences, because it touched on themes that were very much a part of his own life. The two central characters in the film, Steve and Curt, both wrestle with the challenge of growing up and leaving a familiar world. On the eve of their departure for an east coast college, Steve is only too glad to be “getting out of this turkey town,” while his friend Curt agonizes over whether it makes sense “to leave home to look for a home.” A teacher chaperoning the high school dance represents an object lesson: he once had a scholarship to Vermont’s Middlebury College, but retreated back to his hometown after only a semester away. By the end of the film, Curt has been persuaded by a mysterious DJ named The Wolfman that “there’s a great big beautiful world out there,” and that it needs to be explored. But Steve, faced with losing Laurie, ultimately opts to stay behind. The famous epilogue of the film reveals to the audience the future of these two young men: “Steve Bolander is an insurance agent in Modesto, California. Curt Henderson is a writer living in Canada.” Howard has said, “The fact that I knew that Steve was going to wind up being an insurance salesman and stay there definitely informed my performance. This was not an entirely adventuresome person.” The final-crawl device, updating the audience on the future lives of the film’s central characters, was soon to become a well-worn movie convention in its own right.

Ray Morton: It’s the first successful film in the career of one of the major directors of the 1970s and one of the major filmmakers of all time, and it was one of the first films to treat teenagers and their lives and concerns realistically, rather than in sitcom fashion or as exploitation fodder. It is also one of the first films to tell teenage stories from the perspective of the teenagers themselves, rather than from an adult perspective, which so many films, especially in the 50s and 60s did.

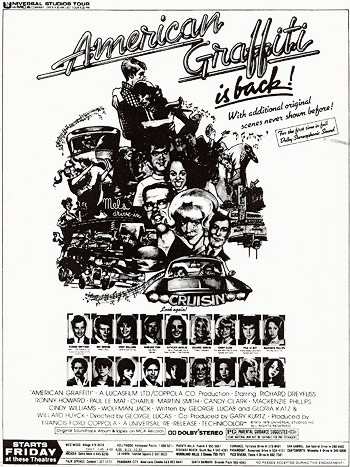

CHAPTER 13: THE 1978 RE-RELEASE

Joseph McBride: Although I generally am supportive of directors adding back material the studios made them cut originally, I don’t think Lucas’s additions particularly helped.

John Cork: I don’t mind the changes. I love the used car scene with John Brent, which was added for the 1978 release, and, apparently, was a cut demanded by the studio in 1973. The “Louie, Louie” sequence at the school dance doesn’t detract from anything for me. Remixing in Dolby didn’t faze me, but movies now have so many mixes for different theatrical and home theater formats that there is rarely a definitive mix on a film.

Ray Morton: I don’t mind the minutes that were added back in because they were taken out by the studio over Lucas’s protestations, so putting them back in was truly a restoration—putting the movie back the way Lucas originally wanted it. The additions don’t radically change the movie except perhaps to make Steve a slightly stronger character when he tells off the chaperone at the dance, although my buddy Brian feels that including the scene of Falfa singing to Laurie was a mistake because “it tries to humanize the character, who is a cocky, arrogant, outsider invading their turf. He’s the villain, you’re not supposed to sympathize until he’s defeated and his steed destroyed.”

John Cork: The only material change I really know about in the 1978 version is the change in the month of John Milner’s death. I didn’t know about that until someone pointed it out to me.

Peter Krämer: What is so annoying about Lucas’s penchant for modifications is the fact that it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to get hold of the original theatrical release versions. And in some cases, there is not even any acknowledgement that changes to that original version were being made. I think that the version of THX 1138 most widely available today is far removed from the original—and on my DVD there is not even a hint that the film ever looked differently.

CHAPTER 14: THE HOME MEDIA EXPERIENCE

William Kallay: This was one of the first VHS cassette tapes I bought once I got a job. My dad had very mediocre speakers, but I would still crank up the sound when I played this cassette.

John Rotan (Dave’s Video/The Laser Place): Aside from the tweaked sunset shot under the main title card, the MCA/Universal Signature Edition of American Graffiti is my personal favorite home video presentation of the film. The solid THX transfer combined with Walter Murch’s immersive sound montage make me feel as if I am right there, cruising through Modesto at night, alongside Curt, Steve, Milner, and Laurie.

John Cork: I certainly don’t mind the sunset shot at the beginning. The original script stated “the sun drops behind a distant hill.” Had they had a bit more money when they shot the film, Lucas would have gotten the shot, and since the film is an ode to an era on which the sun had set, I don’t begrudge him getting the shot like he wanted, even decades later.

Ray Morton: I don’t care for the new CGI sunset, because that’s an example of Lucas doing what we want him to stop doing—altering his old films rather than restoring them. My main objection to the new sunset is that the original blown-out sky is in line with the documentary style of the rest of the movie—that’s what a sunset shot by a doc crew on the fly without the time to perfectly balance the light and capture the sunset would look like. The revised version is too formal, too gorgeous. It feels like something out of a big budget epic rather than a low budget comedy.

William Kallay: I may have bought the LaserDisc, but I do remember getting my first DVD player. In the early days of widespread Internet, I bought the player from a retailer who included 10 DVDs for free. One of the discs I got was American Graffiti. The picture and sound quality for the time was very good and miles above VHS and LaserDisc. Too bad I had mediocre speakers from the same manufacturer as the ones my dad had!

Cliff Stephenson (home media special features producer, Knives Out, Everything Everywhere All at Once): Laurent Bouzereau’s Making of American Graffiti (along with his making-ofs for Jaws, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind) still stands as one of the keystones of the modern “making-of” era. What Laurent did is essentially the same thing producers like me (and, to no surprise, Laurent) are still doing. While the tools to make them have changed and they’ve often become glossier and more tightly edited, the storytelling within The Making of American Graffiti still holds up. Certainly movie making-ofs had existed before, but this kind of retrospective making-of didn’t really exist in that form until Laurent came along. There hadn’t been a market (or frankly the perspective) to look back at some of these films until the 1990s and LaserDisc and DVD were the right formats at the right time to launch this new type of making-of. The fact that twenty-five years after this documentary was created, I’m doing essentially the same thing on titles like Saw X, Knives Out or Everything Everywhere All at Once is a testament to the format Laurent pioneered and The Making of American Graffiti, as I said, is one of the earliest examples of that. It’s also an incredibly important historical document because you get to hear stories and insights from people who are no longer with us. The experiences of Cindy Williams and Suzanne Somers (both of whom we lost in 2023), co-screenwriter Gloria Katz, and visual consultant Haskell Wexler all live on because of the existence of Laurent’s documentary. For as long as American Graffiti lives on as a film, Laurent Bouzereau’s Making of American Graffiti will live beside it. It’s a part of the film now that will accompany every release of American Graffiti forever.

Gary Leva: I had the pleasure of producing George’s video commentary for the Blu-ray of American Graffiti, which I did by simply setting up a camera in The Stag Theater at Skywalker Ranch and letting him talk to me as he watched the film again. What struck me was how sweet the memory of making the film was, despite all the difficulties he and his crew had to endure to get it in the can. They lost locations, had to move to a different city, were chronically underfunded… and yet it all came together. When I produce a commentary with a filmmaker, I study the film thoroughly beforehand. That way, in case he or she runs dry, I can ask intelligent questions to get them going again. So I knew American Graffiti really well when we shot the commentary, and having worked with George for so long—I produced all his Star Wars commentaries as well—I knew what sort of questions would intrigue him. But as well as I knew the film, I learned something sitting with him that day. I realized that all the male characters in the film are aspects of George. There is some of him in the straight arrow Ron Howard plays, some of him in the restless rebel played by Richard Dreyfuss, and some of him in the hot-rodding, grease monkey played by Paul Le Mat. George wanted to be a professional race car driver for years, until he was almost killed in a crash. In a way, Graffiti is like his sweet goodbye to that dream.

William Kallay: Recently, I saw that Netflix had American Graffiti, along with a number of Universal Studios titles, on its streaming service. Eagerly, I clicked on the American Graffiti icon on the screen and was horrified that they were showing it in 16:9! Why in the world, in this day and age of gigantic TV sets, are streamers and broadcasters going back to cropping widescreen images “to fit” them onto the TV screen? This film, and others, do not deserve this butchering. I can remember in the early days of Netflix that they would crop widescreen movies. For shame in 2023.

Bill Hunt (editor, The Digital Bits): Unfortunately, Universal’s recent release of American Graffiti in 4K Ultra HD is rather unpleasant looking. It would appear to be a heavy-handed remastering effort (probably completed circa 2012) that was done by someone who decided that no photochemical grain or fine detail at all should appear in the remastered image. It appears artificially smoothed and decidedly unnatural looking—essentially comparable to Fox’s much-derided Predator: Ultimate Hunter Edition Blu-ray. This 4K release should therefore be avoided at all costs. At the very least, one should try to get a peek at the 4K Digital release before spending money on the physical media version.