”Thunderball will always be the ‘big one.’ When Bond was bigger than anything on the planet, except maybe the Beatles.” — Steven Jay Rubin

The Digital Bits is pleased to present this retrospective commemorating the golden anniversary of the release of Thunderball, the fourth cinematic James Bond adventure starring Sean Connery as Agent 007 and, notably, the first produced in widescreen and, when adjusted for inflation, the most successful entry in the series. [Read on here...]

As with our previous 007 articles (available here, here, here, here, and here), The Bits and History, Legacy & Showmanship continue the series with this retrospective featuring a Q&A with an esteemed group of James Bond authorities who discuss the virtues and shortcomings of Thunderball. The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

The participants…

Jon Burlingame is the author of The Music of James Bond (Oxford, 2012; and recently issued in paperback with an updated Skyfall chapter). He also authored Sound and Vision: 60 Years of Motion Picture Soundtracks (Watson-Guptill, 2000) and TV’s Biggest Hits: The Story of Television Themes from Dragnet to Friends (Schirmer, 1996). He writes regularly for the entertainment industry trade Variety and has also been published in The Hollywood Reporter, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, and The Washington Post.

Robert A. Caplen is an attorney and the author of Shaken & Stirred: The Feminism of James Bond (Xlibris, 2010). He recently was featured in a segment on SPECTRE for an episode of the BBC World News’ Talking Movies.

James Chapman is a professor of Film Studies at the University of Leicester and is the author of Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films (Tauris, 2007). His other books include Inside the Tardis: The Worlds of Doctor Who—A Cultural History (Tauris, 2006), Saints and Avengers: British Adventure Series of the 1960s (Tauris, 2002), and (with Nicholas J. Cull) Projecting Empire: Imperialism and Popular Cinema (Tauris, 2009). Chapman is also a Council member of the International Association for Media and History and is editor of the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television.

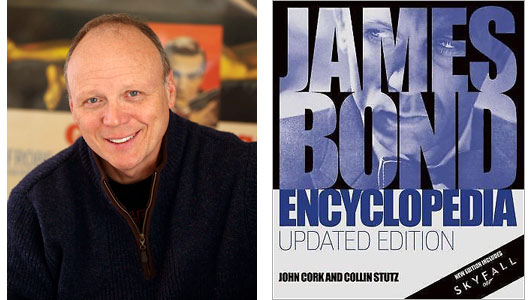

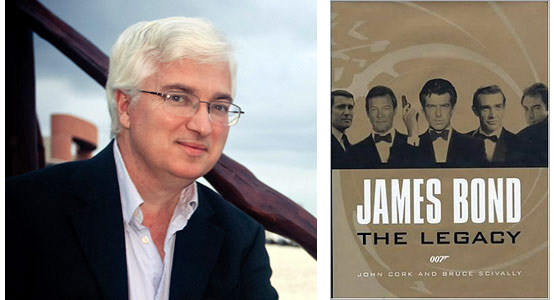

John Cork is the author (with Bruce Scivally) of James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002). He also wrote (with Maryam d’Abo) Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003) and (with Collin Stutz) James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company, producing documentaries and supplemental material for movies on DVD and Blu-ray, including material for Chariots of Fire, The Hustler, and many of the James Bond and Pink Panther titles. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home (1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek. He recently wrote and directed the feature documentary You Belong to Me: Sex, Race and Murder on the Suwannee River for producers Jude Hagin and Hillary Saltzman (daughter of original Bond producer, Harry Saltzman); the film is available on iTunes, Google Play and other streaming platforms.

Lee Pfeiffer is the author (with Philip Lisa) of The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992) and The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001), and (with Dave Worrall) The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999). He also wrote (with Michael Lewis) The Films of Harrison Ford (Citadel, 2002) and (with Dave Worrall) The Great Fox War Movies (20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2006). Lee was a producer on the Goldfinger and Thunderball Special Edition LaserDisc sets and is the founder (with Dave Worrall) and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

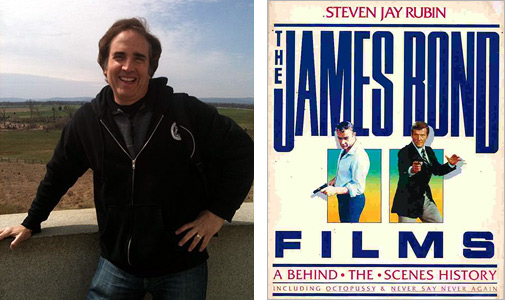

Steven Jay Rubin is the author of The James Bond Films: A Behind-the-Scenes History (Random House, 1981) and The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopedia (McGraw-Hill, 2002). He also wrote Combat Films: American Realism, 1945-2010 (McFarland, 2011) and has written for Cinefantastique magazine.

Graham Rye is the editor, designer and publisher of 007 Magazine and the author of The James Bond Girls (Boxtree, 1989).

Bruce Scivally is the author (with John Cork) of James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002). He has also written Superman on Film, Television, Radio & Broadway (McFarland, 2006), Billion Dollar Batman: A History of the Caped Crusader on Film, Radio and Television from 10¢ Comic Book to Global Icon (Henry Gray, 2011), and Dracula FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Count from Transylvania (Backbeat, 2015). As well, he has written and produced numerous documentaries and featurettes that have appeared as supplemental material on LaserDisc, DVD and Blu-ray Disc, including several of the Charlie Chan, James Bond, and Pink Panther releases. He is the Vice President of New Dimension Media in Chicago, Illinois.

And now that the participants have been introduced, might I suggest preparing a martini (shaken, not stirred, of course) and cueing up the soundtrack album to Thunderball, and then enjoy the conversation with these James Bond authorities.

---

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is Thunderball worthy of celebration on its 50th anniversary?

Jon Burlingame: Where to begin? With Goldfinger, the Bond series really hit its stride in terms of style; the mix of action, suspense and humor; Connery’s performance as 007; and, my special interest, music. Thunderball took it one step farther, and by setting so much of the action underwater, lent a new and intriguing “depth” (sorry) to the screen saga of Britain’s greatest secret agent. I loved the story, in particular; this brought back SPECTRE in a fascinating way—and now here we are, 50 years later, talking about SPECTRE in a new Bond film! Who could have guessed?!

Robert A. Caplen: Thunderball is one of the most intriguing Bond films and novels, complete with the drama of a legal dispute. In the early 1960s, Kevin McClory claimed that the novel infringed upon an earlier screenplay on which he and Jack Whittingham collaborated with Ian Fleming. In light of the pending litigation, Danjaq opted to introduce audiences to James Bond through Dr. No. That decision forever changed the trajectory of the franchise…. When Ian Fleming eventually conceded that his novel reproduced a substantial part of the Fleming/McClory/Whittingham screenplay, a settlement was reached, and Fleming assigned some of his rights in the novel to McClory. McClory then granted Danjaq a license to produce a film version of Thunderball. McClory was given credit as the film’s producer, and the rest is apparently history…. Fast-forward 50 years: the legal issues surrounding Thunderball, once again, reemerged as ownership of SPECTRE and related characters again was the subject of dispute. A recent settlement between McClory’s estate and Danjaq finally resolved the issue once and for all, and paved the way for development and release of the latest Eon Productions installment, SPECTRE. Thunderball is a fantastic film that is more than deserving of renewed celebration during its golden anniversary. But its influence is far-reaching. Thunderball, perhaps more so than other films, plays a central part in an even larger, complex story that enables us to continue enjoying James Bond today.

James Chapman: Thunderball is a major landmark for the James Bond film series. It was the most successful Bond movie of all when the box-office is adjusted for inflation. It was released at the height of Bondmania and the associated spy craze of the 1960s. It was the fourth Bond movie but also marked several “firsts” for the series. It was the first shot in widescreen (Panavision) and the first with a more or less simultaneous release in Britain and the United States. In a sense it was the first really epic (in the sense of “Big”) Bond movie and to that extent the prototype for other “Big” Bonds such as You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker and SPECTRE…. As all Bond fans know, Thunderball started out as a screen treatment by Ian Fleming, Jack Whittingham and Kevin McClory in 1959. This was a couple of years before Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli teamed up to produce the Bond film series. Fleming used material from the screen treatment for the novel. In that sense Thunderball is a very cinematic novel. It was to have been the first film, but due to the court case between Fleming and McClory, and perhaps also because Thunderball would have been expensive to produce, it was decided to make Dr. No as the first film instead…. Kevin McClory is a controversial figure in Bond history, of course. I think that McClory himself probably overstated his role in the origin of the cinematic Bond while Saltzman and Broccoli tended to downplay his role. But McClory deserves credit for recognizing the cinematic potential of Bond. And ultimately Thunderball isn’t very far different from the final version of the Whittingham-McClory treatment. He became rather obsessive over his alleged or perceived “rights” to Bond later in life, but McClory should not be written out of the history of cinematic Bond. Robert Sellers’ fine book The Battle for Bond is the best account of the McClory episode, and he untangles the various contributions of Fleming, McClory and Whittingham to the development of the ultimately aborted project.

John Cork: “It’s the biggest.” Thunderball sold more tickets than any other Bond film. It marks the apex of success of the 007 franchise, the point where Bond was the complete focus on popular culture, the absolutely height of spymania. Thunderball is also the film that would come to define how Bond films would be made even to this day. Using multiple crews shooting major sequences simultaneously, building set-pieces around single “gags” like the Bell-Textron Rocket Belt or the Skyhook rescue system, massive product placement deals, coordinating the release with tie-in advertising and cross-promotions: all of these elements of the Bond series began with Thunderball…. Thunderball is also a very good film, but like so many Bond films, a beautiful mess. Where Goldfinger feels like a film where every shot was planned perfectly, Thunderball plays like live jazz. The fan magazine (and now website) for Led Zeppelin is named Tight but Loose, and that describes Thunderball for me. Just when you think the film is about to go completely off the rails, it pulls it back together. If you can go with the film, it’s like a great Led Zeppelin concert: over-the-top, outrageous, a bit silly, but at times absolutely brilliant, and it even has a drum solo. For me, the film remains one of my favorite Bond viewing experiences. It is also the Bond film with the most amazing behind-the-scenes stories, tales that begin with a famed former aid to a New York City mayor in 1958 and echo through to the release of SPECTRE. In the world of Bond, it all comes back to Thunderball.

John Cork: “It’s the biggest.” Thunderball sold more tickets than any other Bond film. It marks the apex of success of the 007 franchise, the point where Bond was the complete focus on popular culture, the absolutely height of spymania. Thunderball is also the film that would come to define how Bond films would be made even to this day. Using multiple crews shooting major sequences simultaneously, building set-pieces around single “gags” like the Bell-Textron Rocket Belt or the Skyhook rescue system, massive product placement deals, coordinating the release with tie-in advertising and cross-promotions: all of these elements of the Bond series began with Thunderball…. Thunderball is also a very good film, but like so many Bond films, a beautiful mess. Where Goldfinger feels like a film where every shot was planned perfectly, Thunderball plays like live jazz. The fan magazine (and now website) for Led Zeppelin is named Tight but Loose, and that describes Thunderball for me. Just when you think the film is about to go completely off the rails, it pulls it back together. If you can go with the film, it’s like a great Led Zeppelin concert: over-the-top, outrageous, a bit silly, but at times absolutely brilliant, and it even has a drum solo. For me, the film remains one of my favorite Bond viewing experiences. It is also the Bond film with the most amazing behind-the-scenes stories, tales that begin with a famed former aid to a New York City mayor in 1958 and echo through to the release of SPECTRE. In the world of Bond, it all comes back to Thunderball.

Lee Pfeiffer: Thunderball was a blockbuster in every sense of the word and the film that launched Bondmania into the stratosphere. The degree of success of Goldfinger took the producers and the studio by surprise. There were few merchandising opportunities. It’s hard to believe but no one had the foresight to even capitalize on the Aston Martin DB5 when Goldfinger was released in September 1964. Producers Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman weren’t going to let the next opportunity go by. They geared up for probably the biggest merchandise tie-in program since the Disney Davy Crockett craze a decade earlier. Bond toys and merchandise flooded the international market with predictable results. Thunderball was the peak of the Bond boom in the 1960s. It played to packed houses in an era when films didn’t open “wide” in early engagements. Instead, select theaters in big cities got the movie first. You had to wait in long lines to get a ticket. In New York, the Paramount Theater found that even round-the-clock shows couldn’t accommodate the crowds. The film was probably the biggest action-oriented blockbuster ever released. Critics were less impressed than they had been by the previous Bond films, correctly pointing out that with Thunderball, the emphasis was increasingly on gadgetry as opposed to fully fleshed-out characters. However, the movie did have its defenders. It’s the only Bond film to date to make The New York Times list of Ten Best Films of the Year. In any event, audiences loved the movie and a casualty of that success is that the series did become increasingly preoccupied with special effects and hi-tech equipment. This was a gripe of Sean Connery as well. It was probably with this film that he began to lose his enthusiasm for playing 007. Another critic of the movie was its director Terence Young, who felt the film suffered from the abundance of underwater scenes that, by necessity, slowed the action. Fans tended to disagree. Peter Hunt’s editing and John Barry’s superb score went a long way in keeping the final battle sequence exciting.

Steven Jay Rubin: For me personally, Thunderball was the high water mark of the series in the 1960s. After the success of Goldfinger, the appreciation level for anything Bondian blasted off the roof—and Thunderball was its culmination. For my money, it was Connery’s last truly great Bond role. It’s also the most romantic Bond because Bond is matched with arguably the most beautiful woman in the series, lovely French actress Claudine Auger. It has the biggest story, plays on the biggest canvas, and just kicks ass all up and down the line.

Graham Rye: Thunderball was the biggest Bond of all, and nothing that followed ever really matched its overall success, especially for a child of the ‘60s. Ken Adam’s SPECTRE boardroom (far more visually impressive, eerie and effective than its equivalent in 2015’s SPECTRE) and Whitehall Conference Room sets, together with the design of Largo’s yacht/hydrofoil (the Disco Volante) and the visual richness of the film once again immediately told the cinemagoer in 1965 they were unmistakably watching an Eon Productions James Bond film—and to underline that fact, John Barry’s score perfectly complemented the grandeur, action, and intimacy of every aspect of the story—and his composition Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang aptly captured Sean Connery’s confident swagger better than anything else Barry ever wrote. Nobody really understood James Bond like director Terence Young, and in Thunderball it shows in spades. Young undoubtedly molded the young Connery into the Bond role in Dr. No (1962) and in From Russia with Love (1963), in Thunderball his pupil “graduated.”

Bruce Scivally: Thunderball is Bond writ large. From fairly modest beginnings with Dr. No and From Russia with Love to the gadget-filled romp that was Goldfinger, each 007 film had upped the ante from the last. With Thunderball, the film went epic: more gadgets, bigger stunts, and, for the first time, wide screen. After the roaring success of Goldfinger, Thunderball was the film that took James Bond over the top to becoming a phenomenon. The success of those two movies changed cinema and television for the next decade, as spy characters began popping up all over, from The Man from U.N.C.L.E. to Flint to Matt Helm and beyond. But Bond was the king spy of all of them. The Bond films set a bar that, in the 1960s, no other spy adventures would surpass.