Coate: What was your reaction to the first time you saw A View to a Kill?

Caplen: I first watched A View to a Kill on VHS in the early 1990s and enjoyed the film despite emerging with a feeling many critics expressed: had the Bond franchise reached its nadir? But I am a product of the 1980s, so I have nostalgia for the era and for the film, even though it does not rank among my most favorite in the series.

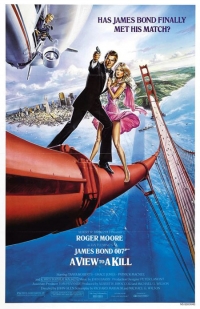

Cork: I was one of those who bought tickets to the World Premiere at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. I went with a platonic female friend who always said I needed to take her to a movie premiere. It was a great evening…. The audience was not filled with James Bond fans. Teenaged girls and their mothers packed the place because two of the members of Duran Duran were in attendance. A girl sitting next to us got into an ugly verbal fight with a girl behind us over something to do with the band. I never figured out what it was about, but all I could think was, “Never thought this would be how it would go down at a James Bond premiere.” The place went nuts when the Duran Duran members walked out on stage…. After that, there was applause when the title song came on and when Duran Duran’s credit came up. Beyond that, the theater was chillingly quiet for a movie premiere until the song was reprised at the end…. That night, the star was not Roger Moore or James Bond. The star was Duran Duran. I think the event was more akin to what it would have been like had they sold charity tickets to the premiere of a Twilight film. But it was a great night…. Reaction to the film: First, I had read the script in advance, so I knew the story. When the film didn’t open with the gun barrel, I was deeply disappointed. I hated seeing a legal disclaimer at the top of the movie. Like the vast majority of Bond fans, the pre-credit sequence had me hooked…until the cover version of California Girls started playing. For a second I wondered if someone had hit the wrong button in the projection booth. It was probably the single most disconcerting moment ever in a Bond film for me…. The film for me never really recovered from that moment. When a fan sees a new Bond film for the first time, you want to be swept away. As a fan, you are invested in the success. Eon and Roger Moore had beaten back Never Say Never Again, making the more successful (and in my opinion) better film with Octopussy. A View to a Kill was teed up to capitalize off of that success. The California Girls moment killed those hopes…. Trivia question for everyone: A View to a Kill’s title song hit number 1 for two weeks in the US in the summer of 1985. Although it is a sound-alike version in the film, did the Beach Boys’ California Girls out-perform or under perform on the Billboard US charts? Answer later!.... There were many highlights, but the film just never fully clicked for me. I now know so many who worked on the film, and each and every one is talented and highly skilled. There is so much great hard work that went into the film, but it never played. I really enjoy Octopussy and The Living Daylights, so this is no knock on John Glen. Sometimes it just works out that way.

Desowitz: I saw it at a press screening at the Academy in Beverly Hills. My reaction was that the franchise seemed tired and it was time for Moore to retire as 007. At the same time, Walken seemed under-utilized.

McNess: I first saw A View to a Kill at the local cinema of the Australian town I grew up in (Portland, Victoria). Not in 1985, mind you, but 1986—it took new releases an inordinately long time to reach us! I liked the film in spite of myself—Indiana Jones was the bee’s knees for me back then. But I also found A View to a Kill intriguing: it wasn’t as action-focused as many other Bonds, instead drawing its energy as much from a quiet sense of foreboding. I also felt that Christopher Walken and Grace Jones gave the film a distinct flavor. I remember the odd beauty of the airship floating over San Francisco Bay, with Zorin anticipating Bond’s demise. And I remember people muttering outside the theater afterward about how “horrible a man” Zorin was.

Pfeiffer: I first saw the film at an advanced critics screening in New York. My reaction was the same as when I saw both The Man with the Golden Gun and Moonraker: “The Bond series is over!” I loved the previous film, Octopussy, because I thought it had the right balance of thrills and humor. But the Moore films were highly erratic in terms of their tone. Most of the true believers in the franchise judged each of Moore’s entries by the amount of embarrassing slapstick humor the movies contained. Thus, Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me, For Your Eyes Only and Octopussy were generally regarded as not having gone “over the top,” although each of those movies do contain some cringe-inducing jokes. However, they did not overwhelm the overall experience. With A View to a Kill, however, the overall perception from fans was one of despair. The silly humor is strewn throughout the movie, culminating in that awful Keystone Cops-like fire truck chase. The film regains its mojo in the last section, but by then the damage is done. But every time I was ready to write the series off, the producers managed to rally and reinvent 007 as a relevant action hero.

Scivally: I saw A View to a Kill at the Cary Grant Theater at MGM in Culver City (now the Sony lot), at a press screening a few days, or maybe a week, before the film opened…. The first few minutes of AVTAK are great. The John Barry music is fantastic, Bond finding the dead agent in the snow is macabre, and the action that immediately follows is exciting and well-paced. And then, three and a half minutes in, we get a cover-band version of California Girls as Bond improvises a snowboard. That scene in itself isn’t so bad; try watching it with the sound off. It’s the music that kills it, instantly destroying the tension that’s built up for the sake of a cheap laugh. And that, in a nutshell, is my biggest beef with John Glen as a director. He’s a very nice man and a great raconteur, but he never understood the difference between “wit” and “vulgar humor.” Once the Beach Boys song starts, the rest of the pre-credits scene devolves into silliness, including the Union Jack on the inside of the iceberg-camouflaged submarine…. Then we’re into the title song by Duran Duran. The song’s lyrics don’t make a lick of sense, but the song itself is catchy and has the bombastic feel of a 007 theme. Maurice Binder’s title visuals, however, are among his worst. Personally, I don’t find women in garish blacklight paint pretending to ski terribly sexy or alluring…. It is fun to see Patrick Macnee in the film. For those like myself who grew up watching reruns of The Avengers on television, it was a treat to see John Steed on-screen with another 60s TV icon, The Saint. Moore and Macnee had appeared together before—Macnee was Dr. Watson to Moore’s Sherlock Holmes for the 1976 TV movie Sherlock Holmes in New York. On-screen, the two have an easy rapport, and superb comic timing, that is a joy to watch. It’s a pity that Macnee’s character, Tibbett, is killed off halfway through the film (though one has to admit he’s not much of a spy if he gets into his car without at least a glance at the tall woman hiding in the back seat)…. It has the weakest fight scene of the series, with Moore and Macnee taking on a guy who looks like Kenny Rogers and another Zorin thug in the secret lab beneath the stables. The fight is oddly choreographed and poorly edited; after Bond punches Kenny Rogers, it looks like Kenny lays himself down on the crate-banding treadmill. And the blue tracksuit Bond wears in the scene looks a size too big, unlike the nicely-tailored suit Moore wears in the previous scene…. The violence of the mine scene, with Zorin laughing gleefully as he machine-guns his men, was more barbaric than anything that had been seen in any previous Bond film. Previous 007s had traded in cartoon violence; this scene has a nastiness to it that is unsettling. In a sense, that scene marked the end of the “old Bond.” Just three films later, with GoldenEye, it would be Pierce Brosnan as 007 doing the machine-gunning of dozens at a time. I guess that’s progress.

Coate: Where do you think A View to a Kill ranks among the James Bond movie series?

Caplen: A View to a Kill should be judged within the Moore era, not against the films of any other actor portraying James Bond. It is simply impossible to give AVTAK the same weight as Goldfinger or Skyfall; the films’ objectives—and audience expectations—are completely different. As a Moore film, AVTAK is entertaining, but it ultimately lacks the excitement and urgency of The Spy Who Loved Me or Octopussy. In my view, the grand triumph of Bond’s rescue of Stacey Sutton and descent from the burning city hall building seems more climactic than Max Zorin’s defeat atop the Golden Gate Bridge. Like Zorin’s blimp, much of the film seems a bit deflated, but it remains a spy thriller complete with East-West tensions, a maniacal villain, an enigmatic henchwoman, and an innocent geologist who gets caught up in a scheme far more complex than a hostile corporate takeover of her family’s oil company. It has the classic elements of a Bond film.

Cork: Really? You are asking that about A View to a Kill? That’s cruel. Some film has to hold the distinction of sitting in last place for me. A View to a Kill holds that honor. Wow, I hate saying that.

Desowitz: I still believe it’s the weakest of the Moore Bonds, but I’ve come to appreciate his willingness to show his age more. It’s also fitting that old school chums Moore and Lois Maxwell bid goodbye to the franchise together. And for once it was nice seeing Bond sneak into a lady’s bed to surprise Jones’ May Day and mix pleasure and pain.

McNess: It is often ranked as one of the lesser Bond films, a position I simply cannot support. While I recognize the details that a number of critics and fans typically take issue with—Bond too far past the late thirties prime, Zorin too odd, a reduced action quota, henchwoman turns good, horse racing episode not sufficiently related to central conspiracy, and so on—I believe the film plays superbly. The inclination to break a genre film down to its constituent parts in order to grade it is understandable, but shouldn’t the grading relate more to how those elements interact? I rank A View to a Kill as one of the best.

Pfeiffer: I would rank A View to a Kill pretty much near the bottom of the Bond barrel. I think only The Man with the Golden Gun and Die Another Day are less rewarding experiences because they didn’t even have memorable title songs. Having said that, there are still plenty of things in any Bond movie that I like, this one included.

Scivally: A View to a Kill, to me, marks the nadir of the series. It has all the ingredients you expect of a Bond film—the gun barrel opening, John Barry score, great theme song, exciting action set pieces, exotic locations, a megalomaniacal villain, and a beautiful damsel-in-distress. Yet, unlike the quiche Bond prepares for Stacey, it’s all gooey and undercooked, using ingredients that are too far past their shelf life.

Coate: Did Roger Moore deliver a good performance in this, his final outing as Agent 007?

Caplen: Absolutely. Moore’s portrayal of Bond has been consistent throughout his tenure. Although Moore may have eclipsed himself as Bond by 1985, he remained Agent 007 until it was time for him to say never again.

Cork: I love Roger. He is a relaxed, confident actor. He can win you over with a glance. I think he did a fine job with a script that probably needed another few months of work. In A View to a Kill, Roger’s performance reminds me of that line in Elton John’s Candle in the Wind: “You had the grace to hold yourself while those around you crawled.” Roger was always a class act on screen, and his performance in A View to a Kill just confirmed his professionalism.

Desowitz: I like the way he acts like a protective father figure to Roberts. It’s lovely watching him cook quiche for dinner and fall asleep in a chair with a shotgun in his arms, watching over her like a gallant knight.

McNess: It’s not the performance that typifies his reign, but it’s a good one. One of earlier quips in the film—”There’s a fly in his soup”—is delivered by Moore at a lower pitch than we’re generally accustomed to, and it sets up the tone of his performance beautifully. The characteristic lightness of touch is, at times, discernibly strained; there are moments of grimness and fatalism threaded through his cool, collected seventh essay of the 007 character. And a quality I find especially engaging in Moore’s performances, particularly in the John Glen films, is how genuinely Moore communicates worry and concern. His Bond also seems quite repelled and unsettled by Zorin, which is an unexpected but welcome detail.

Pfeiffer: Roger Moore has the most self-deprecating sense of humor of any actor I’ve ever known. He doesn’t have a trace of ego. I was interviewing him once on stage at The Players club in New York and I asked him what his best performance was. He said, “None!” The audience lapped it up because it’s so refreshing to find someone who is a show business icon who isn’t full of self-importance. He elaborated by saying his limits are raising either one or both eyebrows to show emotion. I challenged him on that and he conceded he felt he gave one fine performance, in the little-seen 1970 thriller The Man Who Haunted Himself. Of course, that’s all nonsense. If Moore never gave a performance that cried out for an Oscar, he never gave a bad one, either. You know what you’re getting with Moore—and people like his on-screen persona. In the weakest of the Bond films, A View to a Kill included, Moore carries the show and often overrides the elements of the films that don’t work. In real life, he’s one of the funniest people you will ever meet, and that comes across on screen in all of his movies. In View, Moore seems to be having a good time, especially in scenes with his old pal Patrick Macnee. Moore is fun to watch even in a sub-par entry like this.

Scivally: I can’t really fault Roger Moore’s performance in A View to a Kill. As in all his latter Bond films, he seems to find a good balance between the light moments and the ones that require more gravitas. His appearance is another matter. Though it was made only two years after Octopussy, Moore looks a decade older. It is hard to reconcile the deep lines of his face with the athletic heroics of stunt doubles skiing off precipices, jumping atop Eifel Tower elevators, and fighting hand-to-hand atop the Golden Gate Bridge. Mind you, I say this realizing that Moore, in this film, is only four years older than I am presently, and he’s much more handsome at 57 than I am at 53, but he’s not playing Roger Moore. He’s playing James Bloody Bond, a character one usually pictures as being about 35, with the grace of a panther, not the measured moves of an elderly lion. This becomes particularly problematic in the scenes where Bond is trading sexual innuendo with Jenny Flex, making love to May Day, sharing a hot tub with Pola Ivanova, and, in the finale, showering with Stacey Sutton. Bond comes off not as a suave seducer, but as, at best, a dirty-old-man and, at worst, a sexual predator…. It was, I believe, one Bond too many for Moore; it would have been better had his last 007 film been Octopussy. Even he has admitted that by this point he was definitely too old for the role. But if I were offered $5 million plus 5% of the US profits (resulting in a final payday of $7.5 million), I wouldn’t turn the part down on principle, either.

Coate: In what way was Christopher Walken’s Max Zorin a memorable villain?

Caplen: Christopher Walken is a talented actor who imbued Zorin with the necessary maniacal and sinister mannerisms that make him a classic, deranged villain. Can another actor bring to life the personality of a botched Nazi medical experiment in the same way? Likely not…. Zorin, though, is very predictable and unremarkable. It is May Day who is the more memorable villain. We know little about her other than she serves Zorin both professionally and romantically. But is she a product of Zorin’s doping experimentation? Like other villains before her, May Day is impervious to Bond’s charm. But her epiphany occurs out of pure self-interest and self-preservation, which begs the question why she would be so devoted to Zorin in the first place. She thought he loved her. Despite her brawn, May Day is quite naïve and vulnerable.

Cork: Christopher Walken is one of the great American actors of our era. He has been in some of the best and worst films ever made, and in each one, he’s so much fun to watch. From his dark comic turn in Annie Hall, to his amazing performance in The Deer Hunter, to his great tap-dance striptease in Pennies from Heaven, to Pulp Fiction to Catch Me If You Can to Jersey Boys (a film I liked more than almost anyone else). And he’s gotta have more cowbell. Walken is always interesting. You can always see that hint of madness in his eyes…. Zorin himself is a great character, in his own way he reminds me of DuPont in Foxcatcher, a man slipping the bonds of sanity, but so rich no one will stop him. I think there was much more that could have been done with Zorin. Roger Moore hated the massacre in the mine sequence, this film’s version of Goldfinger’s gassing of the hoods, but when I see Walken play that moment, see him live out that bloodlust for the sake of bloodlust, I can see the film that might have been, I can see the shadow of the Joker from The Dark Knight.

Desowitz: The bleach blond hair was a nice throwback to Red Grant, and he was a petulant, spoiled brat. His Scarface-inspired machine gun rampage also took Bond villainy into the ‘80s.

McNess: Walken’s Zorin provides a memorable spin on the patented Bond super-villain. There’s the off-hand joviality; the world’s an amusing playground for Zorin. But he’s also dead-eyed—there’s a disconnect that is actually genuinely sinister. His plans don’t even seem informed by a set of ethics, however debased. It’s monopoly for the sheer hell of it. In terms of Bondian villains we have seen over the decades, he epitomizes the scarily entitled individualist—a prevalent beast in 1980s culture, with no signs of abating in intervening years.

Pfeiffer: Christopher Walken’s presence in the film was quite a coup for the producers. He had won the Oscar for The Deer Hunter a few years before so it gave some real credibility to the film to have an Oscar-winner on board. Of course, since then, numerous people who appeared in the series have won Oscars: Sean Connery, Javier Bardem, Judi Dench, Halle Berry. I might be missing some…oh, yes, John Barry, who technically “acts” in The Living Daylights. Back to Walken…he jumped at the chance because he grew up on Bond flicks and loves them. I thought he did a good job as Zorin. Unfortunately, the character wasn’t very memorable, but he has that wry wit and charm that all the great Bond villains must possess, and his dialogue with Moore is sharp and funny. I also love his last seconds on screen, when he’s about to plunge to his death from the Golden Gate Bridge. He appreciates the irony of having been bested and smiles a bit before falling. It may be the best moment in the film.

Scivally: Christopher Walken is a fine actor, with eccentric phrasing that makes the most banal lines interesting. And his villain, Max Zorin, is not your run-of-the-mill megalomaniac. We’re told he’s the result of Nazi experiments in steroids (along with May Day, we presume) conducted by Dr. Karl Mortner (Willoughby Gray, channeling his inner Josef Mengele). But he’s also part greedy Gordon Gekko, and part Lex Luthor. Like Gene Hackman’s Luthor in 1978’s Superman, Zorin plans to set off an explosion to cause an earthquake that will alter the California landscape. We’re also told Zorin is psychotic, and Walken makes us believe that with the massacre of his own men in the mine, and the nervous giggle he gives before dropping to his death from the Golden Gate Bridge. Unlike some of the other performers, Walken makes interesting choices and strikes all the right notes as Zorin.