The participants for this segment are (in alphabetical order)….

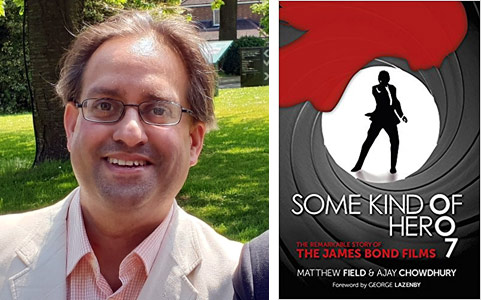

Ajay Chowdhury is the author (with Matthew Field) of Some Kind of Hero: The Remarkable Story of the James Bond Films (The History Press, 2015; updated paperback edition to be released in July 2018). Born in London and read Law at university there and in The Netherlands, Ajay has consulted on various motion picture, music, publishing, television and theatrical projects and has been involved with British and European feature film production in various capacities including developing screenplays and raising finance. He was the associate producer on Lost Dogs (2005) and Flirting with Flamenco (2006) and has been an Advisory Board member on Tongues On Fire who present the London Asian Film Festival.

Thomas A. Christie is the author of The James Bond Movies of the 1980s (Crescent Moon, 2013). His other books include The Spectrum of Adventure: A Brief History of Interactive Fiction on the Sinclair ZX Spectrum (Extremis, 2016), Mel Brooks: Genius and Loving It! (Crescent Moon, 2015), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Pocket Movie Guide (Crescent Moon, 2010), John Hughes and Eighties Cinema: Teenage Hopes and American Dreams (Crescent Moon, 2009), and The Cinema of Richard Linklater (Crescent Moon, 2008). He is a member of The Royal Society of Literature, The Society of Authors and The Federation of Writers Scotland.

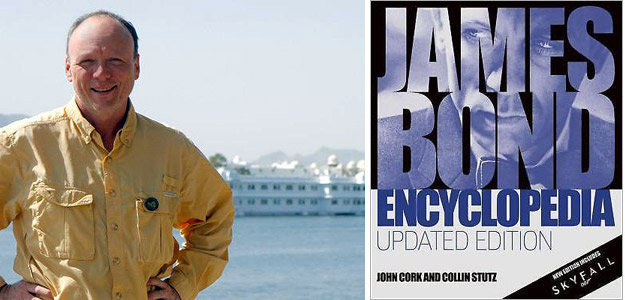

John Cork produced the special features for the home entertainment release of Octopussy. He is the author (with Collin Stutz) of James Bond Encyclopedia (DK, 2007) and (with Bruce Scivally) James Bond: The Legacy (Abrams, 2002) and (with Maryam d’Abo) Bond Girls Are Forever: The Women of James Bond (Abrams, 2003). He is the president of Cloverland, a multi-media production company. Cork also wrote the screenplay to The Long Walk Home (1990), starring Whoopi Goldberg and Sissy Spacek. He wrote and directed the feature documentary You Belong to Me: Sex, Race and Murder on the Suwannee River for producers Jude Hagin and Hillary Saltzman (daughter of original Bond producer, Harry Saltzman). He contributed new introductions for the original Bond novels Casino Royale, Live and Let Die, and Goldfinger for new editions published in the U.K. by Vintage Classics in 2017.

Lee Pfeiffer is the author (with Dave Worrall) of The Essential Bond: The Authorized Guide to the World of 007 (Boxtree, 1998/Harper Collins, 1999) and (with Philip Lisa) The Incredible World of 007: An Authorized Celebration of James Bond (Citadel, 1992) and The Films of Sean Connery (Citadel, 2001). Lee was a producer on the Goldfinger and Thunderball Special Edition LaserDisc sets and is the co-founder and Editor-in-Chief of Cinema Retro magazine, which celebrates films of the 1960s and 1970s and is “the Essential Guide to Cult and Classic Movies.”

The interviews were conducted separately and have been edited into a “roundtable” conversation format.

And now that the participants have been introduced, might I suggest preparing a martini (shaken, not stirred, of course) and cueing up the soundtrack album to Octopussy, and then enjoy the conversation with these James Bond authorities.

Michael Coate (The Digital Bits): In what way is Octopussy worthy of celebration on its 35th anniversary?

Ajay Chowdhury: To help understand why the film is worthy of celebration now, one must first understand the context in which Eon’s 13th Bond film was unleashed. Upon its release in 1983, Octopussy celebrated James Bond’s 21st cinematic birthday. With the likes of then-President Ronald Reagan toasting a fictional 007 on a promotional TV show, James Bond came of age. Implicitly, faced with Sean Connery’s return as Ian Fleming’s agent in Never Say Never Again, Octopussy pulled out all the Eon stops: a repositioned Whitehall brigade of M (now played by Robert Brown), Moneypenny (assisted by Penelope Smallbone) and Q (in his largest role yet), overt use of Monty Norman’s James Bond Theme (“Such a charming tune”) and innovative action on air and on land, helmed by now confident Bond veteran, John Glen. All this anchored by the late, great Roger Moore in an age-defying, sixth and confident turn as the character which, by now, he had made his own.

Thomas A. Christie: Strangely, given that Octopussy is generally regarded as one of the more slow-moving and character-driven entries in the Bond cycle, it is easy to forget just what a gift it was for the media at the time. With Sean Connery reprising the role for the first time in over a decade in the independently-produced Never Say Never Again in the same year, and the very real question of whether Roger Moore would be moving on from the role, the series would achieve renewed cultural relevance with much attention being focused upon the question of which movie would win the head-to-head battle between two vastly popular Bond actors. While Octopussy would ultimately emerge victorious at the box-office, the Cold War-centric plots of both films gave them a contemporary edge and sense of socio-cultural significance that had debatably been on the wane for some years, re-energizing audience interest at a time when the action movie genre was entering a kind of cinematic golden age that would continue throughout the 1980s and beyond. Yet in a number of ways Octopussy was also slightly atypical for a Bond movie at the time, deliberately paring back a reliance on overly familiar tropes in ways which allowed a pertinent, timely geopolitical parable to emerge throughout the narrative with greater confidence than in many other features of the cycle.

John Cork: Octopussy represents James Bond as one of the worst secret agents in the history of espionage, and yet he’s so self-assured, so smug that he takes the day. This is a film with audacity, absurdity, unintentional comedy, a painfully boring theme song, but it just works. This is a movie where Bond dresses up both as a gorilla and a clown, a movie filled with twins / doppelgangers, a Bond movie that seems to harken to the past rather than the future, but it is always fun to watch.

The movie’s pre-credits scene is a perfect example: Bond drives to a horse show conveniently next to a military base in an Argentina-like country. This was shortly after the Falklands War, but all the military officials look like they were extras from the Woody Allen film, Bananas. Bond coolly adopts the disguise of a Colonel whose name he clearly does not know, then starts to leave before he’s reminded that he needs to put on his fake mustache. He promptly gets captured and is only saved because his trusty accomplice Bianca is paying attention. For reasons that completely defy logic, two of his guards taking him off-base in a jeep are wearing parachute packs on their backs. In the history of all the militaries in all the world, no security detail for a prisoner in a jeep has ever worn a parachute. Bond soon hops into the BD-5J “Acrostar” jet which, apparently, he did not properly fuel. A few minutes into his flight, he seems surprised when it runs out of gas. But the scene is brilliantly entertaining. Audiences loved every second of it. Using old-school effects, a real Bede jet, fantastic stunts, and one of the greatest miniature explosions ever, this is the best pre-credits scene of the 1980s.

That’s Octopussy. It’s one fake mustache away from being a complete disaster, but somehow it pulls everything off and ends up sitting pretty.

Lee Pfeiffer: I’m pretty much out there on my own with this, but Octopussy has always been my favorite Roger Moore Bond film. The conventional wisdom among fans is that The Spy Who Loved Me is generally regarded as his best, and while I do love that film, Octopussy has an off-beat, more exotic quality probably because it combines the India locations with major set pieces behind the Iron Curtain. It’s a bizarre, audacious premise but they pull it off well.

Coate: Can you describe what it was like seeing Octopussy for the first time?

Chowdhury: My journey to Octopussy was particularly memorable. My cousin, Raj Singh, had visited the set of the film in 1982 prior to him starring as Zalim Singh, the adolescent Maharajá of Pankot in Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom. Raj had told me about the Udaipur setting he had seen recreated. As a 12-year-old Englishman of Indian extraction, I was intrigued by this.

Early in 1983, my parents were selling their home and a prospective purchaser was a costumier on the film. We lived 20 minutes from Pinewood Studios in North West London and I was regaled with tales of the circus ending of the film. Heck, this was pre-internet 007 gold!

On 6th June 1983, I watched the ITV broadcast of the Royal Premiere of the film and the aforementioned James Bond: The First 21 Years, the star-and-President studded celebration of 007. Together with an embryonic collection of magazine cuttings, by the time the film wended its way to the less expensive suburban cinemas, I was fizzing like Alka Seltzer in a flute of Bollinger.

On what must have been a Saturday afternoon in early August 1983, I queued with my entire family — with many other entire families — round the block of the Harrow Granada cinema. No different from now, the eventual viewing of a Bond film at the cinema is the end of a long, anticipated, clue-studded wait. Seeing Octopussy was the tip of the tentacle of my enjoyment. And enjoy it I did, leaving the cinema on an all-time high. Octopussy is a tight, considered Cold War-themed thriller wrapped in a sun-never-sets-on-Empire fantasy. Roger Moore embodied Cool Britannia before the term had been invented. Arguably, it is the most iconic of the Eighties Bond films with the Acrostar pre-title sequence becoming the memorable set-piece of the movie.

Christie: Back in the eighties, there was a real sense that Octopussy marked a determined attempt by the Bond production team to reassert the Cold War roots of the series — arguably even more so than had been the case in For Your Eyes Only. I first saw the movie midway through the decade on VHS, and was rather struck at the time by the way that there seemed to be more of an effort to play down the more fantastical elements that had become common to the series, putting greater emphasis on dialogue, character development and plot dynamics. Scenes like the tense backgammon game between Bond and Kamal Khan may well have seemed out of place in some other movies in the cycle, but here they seemed perfectly pitched given the rather more stately pace of the narrative. Yes, naturally there are elements of exotic travelogue, the obligatory chase sequences, cutting-edge Q-Branch gadgets, and all of the expected fight scenes remain present and correct. But this really felt like a darker, more mature Bond movie that was consciously working to downplay the increasing level of heightened technological fantasy and knowing whimsy that had manifested itself from the mid-seventies onwards, instead embracing the grittier strain of realism evident in John Glen’s directorial debut For Your Eyes Only and continuing along the same vein.

Cork: I saw Octopussy in New York City at a critics screening at a theater on Times Square. I was staying with a film critic, Tom Sullivan, for whom I had interned years earlier. I attended with him. The crowd loved it. I was scheduled to meet a girl who was in the same program in college with me after the screening. I had enjoyed the film so much that I figured out a way to sneak her in for the second critics screening a half an hour later.

Pfeiffer: I saw the film at the Loew’s State Theatre in Times Square at an advanced critics screening. I liked it immediately. I had mixed opinions about the previous Bond film, For Your Eyes Only, though I have warmed to it over the years. I felt that while it was a major improvement over the slapstick of Moonraker, it was still too silly in parts. I thought that the balance of humor and thrills in Octopussy was exactly right… though I still cringe at the scene in which Bond makes that Tarzan yell while swinging from a vine. The plot is complex…in fact, it’s too complex and I still find it hard to figure out all the intrigue about the egg. Someone tried to explain it to me once and midway through their explanation, they determined that even they didn’t quite understand it. But it’s a lively, fun film with Moore in top form. It also has a very good title theme song and a marvelous John Barry score. The script is witty even when it’s confusing and it’s very well cast.

Coate: In what way was Louis Jourdan’s Kamal Khan a memorable villain?

Chowdhury: That professional Frenchman Louis Jourdan was cast as the exiled Afghan Prince Kamal Khan says a lot of about the film industry of the time. Try getting away with that now! Known India-phile, George MacDonald Fraser had originally envisaged a more typical subcontinental buccaneer-type with flowing robes and a black turban. As played by Jourdan, he matched Roger Moore for urbane suaveness and his Hollywood background gave the film an elevated air of class. He has a number of classic scenes including a backgammon duel where he is ingeniously outwitted by Bond — he hisses the Fleming line, “Spend the money quickly, Mr. Bond” — and the dinner at the Monsoon Palace where he devours a sheep’s eye to the audiences’ and Bond’s obvious disgust.

Christie: Kamal Khan was a slightly problematic antagonist, in the sense that while the late Louis Jourdan was undeniably an actor with abundant charm and sophistication, he seems to be overshadowed at every turn by Steven Berkoff’s snarling, posturing Soviet zealot General Orlov — nominally the secondary villain of the movie. It doesn’t help that Orlov’s aims are so much more tangible in nature: the collapse of the Iron Curtain and the expansion of the USSR’s military influence into Central and Western Europe, thus tipping the balance of the Cold War in favor of totalitarianism. Khan may well be the shadowy figure behind the scenes whose schemes are helping to aid the general’s illicit objectives, but the convoluted nature of the bait-and-switch plot concerning the smuggling of priceless Russian art treasures into the West (with the originals being painstakingly duplicated and returned to Moscow) seems oddly genteel compared to the nuclear warhead-triggering intrigues employed by Orlov. While the detailed expository scene at the beginning of the film makes it clear that Orlov’s reckless actions are not sanctioned by the Soviet leadership, throughout the film the threat posed by the character seems so much more immediate than that of the film’s comparatively sedate central adversary. In this sense, of course, Khan seems like a natural progression of the more grounded Bond villain heralded by Julian Glover’s charismatic, manipulative Aristotle Kristatos in For Your Eyes Only, in that he was willing to use Cold War geopolitics not for ideological ends (as Orlov intends to), but rather because of the personal benefit he could obtain from playing both sides against each other. This was a theme to which screenwriters Richard Maibaum and Michael G. Wilson would return in A View to a Kill, and most especially The Living Daylights, later in the decade.

Cork: Louis Jourdan wins the prize for playing the most unctuous Bond villain. He had tragically lost a son to a drug overdose in 1981. He had all but retired by that point, doing occasional TV appearances, but his friends urged him to dive back into work as a form of therapy. He had played a villain in Swamp Thing, which everyone thought was a disaster, but Cubby Broccoli was a friend and he decided to cast Jourdan. Jourdan had memorably played a villain in the Doris Day film Julie back in the mid-50s, which coincidentally ends with a deadly battle on a plane in flight. Jourdan was a lot of fun to watch. Some of the cast and crew described him as “prickly,” always wanting to go over his lines, adjusting a word here or there, but I think that meticulousness shows in his performance. Unfortunately, his character is ostensibly working for Octopussy, and he has multiple scenes where he is seen kowtowing to her. This does little to create a character that we fear or respect. I wish he had a great moment of villainy, some scene that celebrated the character’s dark heart in a particularly chilling moment. Nonetheless, the way he says the name, “Octopussy” is just so delightful. He’s a great actor.

The real villain of the film is General Orlov, played masterfully by Steven Berkoff. He seems to channel a bit of George C. Scott from Dr. Strangelove, but he makes every scene he’s in leap off the screen. The war room scene where he perfectly articulates the Reagan-era fear of a conventional invasion of West Germany is appropriately chilling. His attempt to force NATO to unilaterally remove nuclear weapons from Europe is both believable and brilliant. When Bond confronts Orlov about the consequences of a nuclear explosion on a U.S. military base, he points out that NATO will certainly retaliate. Berkoff plays his line perfectly. “Against whom?” he asks. He is so good that his scenes lift up the performances of everyone around him. Orlov is a great character, wonderfully written, played to the hilt. I wish he had lasted until the end of the film rather than foolishly and needlessly getting shot at the East German border.

Pfeiffer: While Khan isn’t a larger-than-life Bond villain, he fits the bill suitably. He’s dapper, witty, debonair, and proves to be a good match for Bond. Supposedly Jourdan felt out of place on the set. He was from the old world studio system and had never made anything like a Bond film previously. Word is that he found the entire experience to be somewhat bizarre compared to all those films he had shot on MGM sound stages, but he comes through admirably. He’s especially good in the requisite scenes in which he banters politely with Bond, even when he describes how he intends to give him a mind-killing truth serum.

Coate: In what way was Maud Adams’ Octopussy a memorable Bond Girl?

Chowdhury: Casting director Jane Jenkins had originally looked to cast Indian actresses as Octopussy including Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s bald beauty, Persis Khambatta. However, again, in a sign of the times, Maud Adams was eventually re-cast as the title character. Trailed as the first female Bond villain, Octopussy has a depth of background drawing cleverly from the eponymous 1966 posthumous Fleming short story. Adams had gained in confidence and her mysterious introduction feeding her pet octopus is atmospheric and bodes well. Adams’ scenes with Moore sizzle — especially where she dresses 007 down as a paid assassin and daring him to become two of a kind and move with her as one. Adams did the best with a poorly written part — MacDonald Fraser has her name revealed to be October Debussy — whose villainy is co-opted by her male co-stars. She is athletic in the Monsoon Palace attack and beautiful in a sari and acquits herself with grace and poise.

Christie: Octopussy may well be a movie which has been blighted by claims of cultural chauvinism over the years, but there was no denying the robust feminist credentials of its eponymous figure. Maud Adams’ Octopussy is smart, resourceful, and perceives Bond more as a useful instrument to achieve her goals than as the singular answer to her problems. In that sense she owed more to the tradition of strong, highly-skilled female supporting characters such as Anya Amasova and Melina Havelock than she would to the somewhat less independent Stacy Sutton who was to appear in Moore’s swansong A View to a Kill. The audience could believe without question that Octopussy is such an intelligent and quick-witted character, with undeniable qualities of leadership and organizational ability, that she is perfectly capable of taking on the film’s antagonist directly with no necessary involvement from Bond; a fact which is emphasized by the highly effective assault on Khan’s palace by her employees, which she orders when the scope of his treachery becomes clear. Rather than diminishing Bond’s relevance, Octopussy’s unwavering competence, ingenuity and autonomy make the on-screen pairing an interesting match of professional skills and understated romantic chemistry which was handled with customary proficiency by both Adams and Moore.

Cork: Octopussy was the first attempt to do a full-scale female Bond villain. She’s very much inspired by Pussy Galore, even down to having her own “flying circus” (of acrobats, not pilots). And like Pussy Galore, she’s really a good girl at heart once she’s slept with 007. There is something that dances into Tennessee Williams territory when she sleeps with the man responsible for her father’s death, but I’ll leave that to Octopussy’s therapist to handle. She also reminds me, oddly, of Marnie from the Hitchcock film starring Sean Connery in that she’s an obsessed kleptomaniac with sexual issues. Maud Adams is good in the role, but I miss the film where she’s the actual villain. As it is, she has far too little to do. She never seems essential to the plot.

The father of the cinematic character of Octopussy is one Major Dexter Smythe. Smythe commits suicide when confronted by Bond over the murder of a mountain guide some years previous. In the film, Bond refers to Smythe’s “native guide.” All this is a reference to the original Ian Fleming short story Octopussy. In that original short story, where the murder of the guide takes place in Austria, not North Korea, the guide is given a name, Hannes Oberhauser. The literary Bond describes Oberhauser as a father figure after the death of his parents. And in the film SPECTRE, Oberhauser is also the father of Franz, who grows up to become Blofeld. This means in some twisted merged literary / cinematic universe, Octopussy’s father killed Blofeld’s father.

Pfeiffer: I’ve known Maud for many years and she still remains one of my favorite Bond actresses. She was one of the few admirable elements in The Man with the Golden Gun. She has the distinction of being the only actress who played two different major roles in two different Bond films. She’s exquisitely beautiful as Octopussy and kudos to the costume designer for outfitting her so exotically. In the past, some of Bond’s leading ladies were…well, let’s put it this way…they were responsible for eliciting some unintended laughter from the audience. But Maud can act and can deliver some questionable lines of dialogue without the unintended consequences. She and Roger were great friends in real life and remained so. In 2010, Roger was in London and had agreed to appear at an event for our magazine, Cinema Retro. We were able to arrange for him to have a surprise reunion with Maud and Britt Ekland, who was also in Man with the Golden Gun. It was quite apparent how much respect Maud and Roger had for each other.

Coate: Where do you think Octopussy ranks among the James Bond movie series?

Chowdhury: I find ranking Bond films particularly difficult and actually unhelpful and inaccurate. Also, my mood shifts and times change. For me Octopussy was certainly the winner of 1983’s The Battle of the Bonds having a better story and setpieces than Connery’s Never Say Never Again — American fans tend to prefer the latter. Octopussy had too much broad humor which offset the clever and politically astute plot. However, as I outline [in my answer to the next question], as the Bond films moved away from setpieces and locations extravaganzas, one sometimes misses the sheer, unabashed entertainment where Octopussy’s virtues overcome its vices.

Christie: It seems that Octopussy has become a bit of a curio amongst Bond movies, and while unlikely to rank amongst the very best of Moore’s appearances in the role, its Cold War credentials have lent it a kind of contemporary political relevance (shared by its predecessor) that would be largely lacking in Moore’s final performance as Bond two years later. While it could be argued that the conceit of a nuclear incident being deliberately engineered to shift the Cold War status quo was more effectively delineated by Frederick Forsyth’s later novel The Fourth Protocol and its cinematic adaptation, for a Bond film the scenario felt fresh and germane to the glacial geopolitics of the early eighties in ways that demonstrated a shift away from the more grandiose global annihilation strategies of the late seventies entries in the series. However, what may feel like a move in the direction of greater subtlety and finesse in the film’s political commentary would inevitably make it seem remarkably sedate when viewed in the wider context of the Bond cycle, meaning that Octopussy has divided the opinions of both fans and critics since the time of its initial release.

Cork: I enjoy Octopussy. In my 2012 rankings I did with my son, it landed 15th, but that seems low to me today. Yet, when I look at the list, there are no real clunkers above it. It’s not a great Bond film. It’s too long. I never need to see the tuk-tuk chase in India again or cringe at Octopussy thanking Bond for causing her father’s death. But the chase to the airbase in Germany works on a Hitchcockian level, building real suspense. The film is saddled with a lot of silliness, like reaction shots from camels, and the smarmy sex jokes feel a bit creepy, but so much of the film just works.

Pfeiffer: I don’t think it outshines the first six films in the series or Casino Royale or Skyfall, but I do think it can fit snugly in as perhaps my 9th favorite film in the series. So middle-of-the-pack, in my opinion. I watched it last year when I screened the film at the Players Club in New York City, where we inducted Roger Moore as a member some years ago. I was very pleased with the way it held up, not having seen it in quite a few years. It still made me laugh and I believe it’s Roger’s most enjoyable performance as 007. More importantly, the audience, which was comprised not of Bond fans but of private club members, enjoyed it immensely, so I think its merits hold up well today.

Coate: What is the legacy of Octopussy?

Chowdhury: Watching the film now, one realizes they don’t make Bond like they used to. In 1983, they went to real, iconic locations and interacting directly with them: the Berlin Wall and Udaipur are incorporated into the story and action.

Back then, they kept loosely to the Three Girl Formula as coined by Roald Dahl: Tina…good, Magda…bad-ish, Octopussy…good-ish augmented by publicity pulchritude, the Octopussy Girls.

In those days, Bond films were the iron fist of a world affecting caper clad in the velvet glove of an elegant, seemingly unconnected MacGuffin, seasoned with elements of Ian Fleming. George MacDonald Fraser, later rewritten by Richard Maibaum and Michael G. Wilson, confected a Zeitgeist-ian tale of forced nuclear disarmament exploited by a renegade Soviet general unraveled by the trail of a jeweled Faberge Egg, The Property of a Lady.

In 1983 there was still a suave central villain — the Afghan Prince Kamal Khan — assisted by physical heavy with a novel accoutrement: beturbaned Sikh warrior, Gobinda with his yo-yo buzz saw.

The film exemplifies the then typical Bondian trope of many staggered endings. Firstly, we have the nail-biting, absurdist Hitchcockian circus finale. Then, the all-girl assault on the Monsoon Palace, a feminist take on the boiler suit end battle. This is capped by the stinger where the villain and/or henchperson are dispatched using their devices against them. In this case, Bond using the Beechcraft airplane to off Gobinda (the twanging aerial) and Khan (his jacket jamming the airflap). Of course, the film finally ends with an “Oh James” waterborne ending. And, alas, Octopussy is the last Bond to end with the announcement of the title of its successor.

Watching any Bond film is to examine a pop-cultural time capsule but watching Octopussy is to examine how they used to make Bond films and how that process has evolved. For me it is nostalgic exercise, capturing the enjoyment of my youth. May 2017 marked the first time an actor who played Bond in the Eon series had passed. With the death of Sir Roger Moore, watching Octopussy now is freighted with poignancy, evoking the ache of all my unbought yesterdays.

Christie: While Octopussy may always be fated to be best remembered as the Bond film that went head-to-head with Never Say Never Again, its real legacy was to reaffirm the relevance of the series to an increasingly sophisticated international audience that was being presented by a resurgent action movie genre which was offering whole new levels of cinematic spectacle and excess. Whether it can be regarded as vintage Bond, or even a classic of the Moore era, is questionable. However, there is no doubt that the movie did play an important part in ongoing efforts throughout the eighties by John Glen and others within Eon Productions to reinvigorate the series, and that the groundwork laid at the end of Moore’s tenure in the role would act as a foundation for the considerably moodier and more starkly uncompromising approach of the Timothy Dalton films that would appear later in the decade.

Cork: In the film Ted, Mark Wahlberg belts out a terrible version of All Time High at a Nora Jones concert. That moment, in its own way, cemented the film’s place as an icon of 80s pop culture. Moonraker felt like From Star Wars with Love in 1979, and Octopussy feels a little like Raiders of the Lost Bond until it gets back to Germany during the last hour of the movie.

The legacy of Octopussy is, I feel, tied very much to one of the writers, George MacDonald Fraser. He was the original writer on the film. He oriented the story towards India, decided Bond should disguise himself as a clown and a gorilla. He also personally embraced the ideal of the British Empire, and he gave this movie a slightly anachronistic feel of The Raj, or at least Hollywood’s vision of it in films like The Rains Came (1939) with lots of white folks living in luxury and hobnobbing with exotic princes in India. Fraser did quite a bit more, too. This was Fraser’s version of James Bond which is a very different Bond than any other incarnation. Fraser wrote a famous series of novels about a 19th century bully, liar, and coward named Flashman. The brilliance of these novels is Flashman’s ability to seem like a hero despite being anything but. Fraser was also a passionate lover of the writing of P.G. Wodehouse, and Octopussy gives us a Bond who has quite a bit of Flashman and Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster mixed with a dash of Ian Fleming. This Bond is singularly annoying like Flashman (his taunting of Fanning at the auction, for example), utterly incompetent like (Magda stealing the Fabergé egg from him), easily flummoxed like Bertie Wooster (Bond is too intimidated by a woman at a pay phone to get word to the authorities about a legitimate nuclear terrorism threat), yet succeeds in spite of himself. Like Bertie Wooster after putting on blackface to escape a tense moment in P.G. Wodehouse’s Thank You, Jeeves, Bond in clown-face finds himself unable to be believed when he desperately needs help. Like Flashman, this Bond is a prankster, a 007 who would fake injuries that require elevation pulleys to be installed on Octopussy’s barge, all to surprise her when he breaks loose from them to reveal that he’s not injured at all. It is an interesting take on the character, and it worked for audiences. Fraser’s view of Bond is far from my take on the character, but it delivered the last unqualified success of the Bond series until GoldenEye, twelve years later.

Pfeiffer: Coming off the anemic Man with the Golden Gun, the series was in trouble. Grosses were down and Harry Saltzman and Cubby Broccoli had broken up as partners. Cubby saved the day with the opulence and grandeur of The Spy Who Loved Me but went off track with Moonraker. That film was a commercial success but he later told me that he knew they had crossed the line in terms of over-the-top humor. He wanted to bring Bond back down to earth. He achieved that with For Your Eyes Only but that film really only comes alive in the second half. There was still too much zany, Keystone Cops-like humor. Octopussy finally got the formula right. I don’t think most fans appreciate the movie on the same level I do, but I urge them to give it another try.

Coate: Thank you — Ajay, Tom, John, and Lee — for participating and sharing your thoughts about Octopussy on the occasion of its 35th anniversary.

The James Bond roundtable discussion will return in Remembering “Live and Let Die” on its 45th Anniversary.

IMAGES

Selected images copyright/courtesy 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, CBS-Fox Home Video, Eon Productions Limited, Danjaq LLC, MGM Home Entertainment, United Artists Corporation.

- Michael Coate

Michael Coate can be reached via e-mail through this link. (You can also follow Michael on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook)