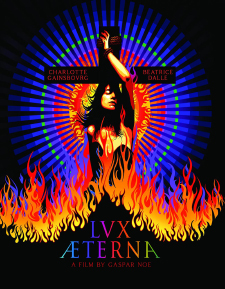

Lux Aeterna (Blu-ray Review)

Director

Gaspar NoeRelease Date(s)

2019 (August 30, 2022)Studio(s)

Vinegar Syndrome/Yellow Veil Pictures- Film/Program Grade: B

- Video Grade: B+

- Audio Grade: B+

- Extras Grade: B-

- Overall Grade: A-

Review

Lux Aeterna is a 2019 provocation from provocateur extraordinaire Gaspar Noe. Noe has long been associated with the what critic James Quandt derisively termed “New French Extremity,” a series of otherwise unrelated films made by a group of filmmakers that also includes Catherine Breillat, Alexandre Aja, and Virginie Despentes. Unlike those directors, Noe’s extremity has been as much formal as anything else, and Lux Aeterna is no exception. The film opens with a quotation from Fyodor Dostoevsky extolling the “extreme happiness” that an epileptic feels in the moments before a fit, and Noe does everything in his power before the conclusion to induce seizures in people who aren’t even susceptible to them. Lux Aeterna runs a scant 51 minutes, but it’s not an experience to be taken lightly—or unadvisedly, for anyone with sensitivity to flashing lights.

There are many layers to Lux Aeterna, as it’s an experimental film that takes place on the set of an experimental film. Beatrice Dalle and Charlotte Gainsbourg play themselves, or rather they play fictionalized versions of themselves, with Dalle as the harried director of a drama about witches, and Gainsbourg as her lead actor. Lux Aeterna begins with a montage of footage from other films about witchcraft such as Haxan and Day of Wrath, but keeps its own distance from that footage by interspersing text that interrogates how some of the footage was produced, including the tortures suffered by one of the actresses. It then features a twelve-minute-long improvised conversation between Dalle and Gainsbourg, relaying some of their own uncomfortable experiences with male filmmakers on set and off. That’s mirrored by the production of their film-within-a-film, as the producers want to fire Dalle, and one of the male actors wants to use Gainsbourg as a means to achieving his own directorial debut. Both Dalle and Gainsbourg are pushed to their limits, leading to a completely chaotic breakdown while filming a scene of witches being burned at the stake.

Actually, most of Lux Aeterna was improvised, with Noe’s script providing the barest of outlines to tie everything together. It’s not a narrative film, nor was it ever intended to be one. There’s a running theme of people being broken down until they achieve an altered state of consciousness, whether it’s Anna Svierkier in Dryer’s Day of Wrath, or Dalle and Gainsbourg in this film, or even the viewers themselves. Whether or not an epileptic feels “extreme happiness” when a seizure is coming, for Noe, the process of achieving it requires pain and sacrifice. As a result, it’s entirely appropriate that Gainsbourg ends up sharing the experiences of Svierkier during the finale, being broken down to a point of near ecstasy by suffering through the filming of her scene. Of course, it’s not really happening to Gainsbourg the actor, but rather to the character of “Gainsbourg” that’s being played by Gainsbourg. So, while the visual and aural assault of Noe’s conclusion is quite real, there’s still some self-referential ironic detachment from it. It’s no accident that Noe closes Lux Aeterna with a quote from the great trickster Luis Bunuel: “Thank God that I’m an atheist.” It’s a reminder that nothing in cinema can be taken at face value.

Cinematographer Benoit Debie appears to have captured Lux Aeterna digitally, but there’s no information available regarding the cameras, lenses, or capture resolutions that were involved, though it likely utilized a 2K Digital Intermediate. While the overall presentation is contained within a 2.35:1 frame, the majority of the film consists of various combinations of 1.33:1 (or narrower) images—either a single one in the center, two of them side-by-side, or three of them spread across the screen. There are a few moments when a single image expands to the full 2.35:1 width, but most of the film utilizes combinations of split-screens. There’s a bit of noise in some of the darkest shots, as well as flatter contrast and slightly elevated black levels, but aside from low-light conditions like that, the overall contrast range does a good job of representing the extreme limits of both ends of the spectrum. Darkness and light sometimes alternate in rapid progression, especially at the climax of the film. The colors are highly stylized, but they all seem accurate to the look that Noe and Debie wanted to achieve. Lux Aeterna is the kind of project that can only be judged according to the intentions of the filmmakers, rather than against some kind of Platonic ideal, and this transfer conveys the chaotic experience that they wanted to provide.

Primary audio is offered in French 5.1 DTS-HD Master Audio, with non-removable English subtitles. It’s largely a dialogue-driven experience, up until the moment that it’s not. There are some reverberations from effects like thunder in the surrounds, but the focus generally stays on the actors who are speaking up front. Then, when visual hell is released during the conclusion, the full aural assault is unleashed, including a repetitive effect that’s designed to enhance the unease caused by the flashing imagery. It’s difficult to watch the ending of Lux Aeterna without looking away or turning down the sound, but that’s the experience that Noe intended. There are two additional audio options that aren’t mentioned on the setup menu, and can only be selected via the audio button on a player’s remote: French 5.1 and 2.0 Dolby Digital. There’s also a secondary close captioning option that adds descriptive text under the non-removable subtitles, as well as English subtitles for the commentary track.

The Yellow Veil Pictures Blu-ray release of Lux Aeterna is a two-disc set that includes the film and its directly-related extras on the first disc, as well as four classic avant-garde short films on the second disc, all of which served as inspirations for Noe. It features a reversible insert with alternate theatrical poster artwork on each side. There’s also a slipcase with 60-page booklet available directly from Vinegar Syndrome, limited to the first 2,000 units. (It’s possible that there’s information regarding the transfer in the booklet, but that wasn’t enclosed in this copy of the film.) The following extras are included, all of them in HD, though one of the shorts (La Ricotta) may have been upscaled from a lower resolution source:

DISC ONE (FEATURE FILM & EXTRAS)

- Introduction by Gaspar Noe (11:02)

- Audio Commentary with Gaspar Noe and Beatrice Dalle

- Lux in Tenebris (6:04)

- Split Screen Video Essay (7:38)

- Lux in Practicus (10:31)

- Theatrical Trailer (1:26)

- Teaser Trailer 1 (:56)

- Teaser Trailer 2 (:53)

The commentary with Noe and Dalle is a lively one, and they candidly discuss some details that were left oblique in the film—for instance, they identify the films that Dalle and Gainsbourg were talking about during their twelve-minute conversation. (For the record, Dalle was referring to Marco Bellocchio’s The Witches Sabbath, and Gainsbourg was describing something that happened while filming Andrew Birkin’s The Cement Garden.) Noe says that a lot of people on the set ended up leaving with headaches after shooting the finale, which isn’t particularly surprising. Note that since the subtitles for the film aren’t removable, the commentary subtitles end up overlaying them, and whenever the pair take a pause, the commentary subtitles duplicate the film’s subtitles. That sometimes makes things difficult to parse, but on the other hand, it’s entirely in keeping with the chaotic nature of the film itself.

The Introduction is only selectable when playing the film, rather than being a separate item in the “Extras” menu. It’s from a screening at The Metrograph Theater in New York, where Noe explains the genesis of the film, and the hasty way that the project was assembled. He says that it almost started as a joke. Lux in Tenebris is a collection of behind-the-scenes photographs and production stills that were shot by title designer Tom Kan. The Split Screen Video Essay is an examination of the use of split-screen imagery in the cinema, from its history in films like Pillow Talk (1959) and The Chelsea Girls (1966) to Noe’s usage of the device in Vortex and Lux Aeterna. It was written and edited by Chris O’Neill. Lux in Practicus is an interview with actor Karl Glusman, who discusses how he became involved with the film, his experiences working with the other actors, and shooting the strobe light sequences. He says that the worst sin imaginable is to make something that isn’t memorable, and he definitely didn’t fall into that trap with Lux Aeterna.

DISC TWO (SHORT FILMS)

- Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (38:29)

- La Ricotta (36:00)

- Ray Gun Virus (14:25)

- The Flicker (29:58)

Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) is a seminal underground film from Kenneth Anger, who is the author of Hollywood Babylon, as well as being one of the most important experimental filmmakers in the history of cinema. Inspired by the writings of English occultist Aleister Crowley, but with a title derived from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s epic poem Kubla Khan, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome has no conventional narrative, but rather a succession of psychedelic imagery as various mythical and historical figures parade across the screen in a bacchanalian display. It was a work in progress for Anger over the course of a couple of decades, with no less than four different versions appearing during that span of time (there were actually five, counting the initial edit that Anger never released). One version exhibited at the 1958 World’s Fair used a triptych projection system, and another was edited to sync with the Electric Light Orchestra album Eldorado. This version is Anger’s 1993 reconstruction of his 1954 version that used Leos Janacek’s Glagolitic Mass as its soundtrack. (For a splendid analysis of the construction of the film and its imagery, see P. Adams Sitney’s classic 1974 book Visionary Film.)

La Ricotta is actually Pier Paolo Pasolini’s segment from the 1963 anthology film RoGoPaG. It features a Marxist director, played by none other than Orson Welles, who attempts to film the passion of Jesus Christ, but things go drastically wrong. Pasolini was a Marxist as well, but he admired Jesus as a revolutionary figure, especially in terms of Christ’s teachings about care for the poor and the needy. Of course, Pasolini would direct his own version of the life of Christ the following year with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, so he had clearly been planning for that while he conceived of this short film. Pasolini was an atheist, but he wasn’t so much anti-religion in general as he was anticlerical, and La Ricotta reflects his condemnation of the superficial piety of the Roman Catholic Church.

Ray Gun Virus (1966) is a flicker film by Paul Sharits, who edited together alternating frames of black, white, and various colors into stroboscopic patterns, with the soundtrack featuring nothing but the sounds of the film strip running through the projector. Sharits described the film projector as being an audio-visual pistol, with the human retina being the target, and his goal being “the temporary assassination of the viewer’s normative consciousness.” There’s no question that Ray Gun Virus achieves that goal, as its hypnotic rhythms work to break down conventional avenues of perception and comprehension.

The Flicker (1966) was created by Tony Conrad, who took the concept of a flicker film to its logical extreme, as the majority of the film consists of nothing but alternating full black and full white frames. There’s a seizure warning at the beginning and a title card, but after that, the film itself is approximately 23 minutes of stark flickering imagery, accompanied by synthesized rhythmic clicking sounds. There are actually 47 different patterns involved that vary throughout the film, ranging from high flicker rates of 24 frames per second, to ones as low a four frames per second. Like many experimental projects, it can be a bit of an endurance test, but it’s a striking reminder of the ways that underground filmmakers pushed the boundaries of the film medium.

Not included from Arrow’s single-disc Region B Blu-ray release of Lux Aeterna is the audio commentary with author Kat Ellinger, and Miranda Corcoran’s visual essay Lux in Extremis. On the other hand, Arrow’s Blu-ray is missing the Introduction by Gaspar Noe, Lux in Practicus, and the Split Screen Video Essay. It’s also missing three of the four short films—only The Flicker is included. While Ellinger’s commentaries are always welcome, the balance definitely tips in favor of this version. The extras directly related to Lux Aeterna are arguably a bit thin, but the inclusion of the four otherwise unrelated shorts raises the value of the whole package to a much higher level.

Yellow Veil Pictures has assembled an impressive collection here for fans of what author Gene Youngblood called “expanded cinema.” That’s actually a more useful term than underground, experimental, or avant-garde, as it accurately conveys the intentions of the artists to push beyond the widely accepted boundaries of the medium. It certainly describes what Gaspar Noe has done all throughout his career, even when he’s worked within seemingly conventional narrative structures. He still pushes the boundaries of what many people will find acceptable—Yellow Veil Pictures has included an epilepsy warning up front, and please take that warning seriously. For those who can handle the stroboscopic imagery contained on both discs, this is an essential collection.

- Stephen Bjork

(You can follow Stephen on social media at these links: Twitter and Facebook.)